Special article on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the United Nations

UN Member States agreed in June 2019 that the UN will mark its 75th anniversary with a one-day, high-level meeting of the UN General Assembly on Monday, 21 September 2020 on the theme, ‘The Future We Want, the UN We Need: Reaffirming our Collective Commitment to Multilateralism’.

India was among 26 countries that participated in the January 1942 Conference of Allied Nations at the invitation of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the United States. The Conference issued a “Declaration by United Nations”, which committed its signatories to the objective of creating what we today call the United Nations (UN).

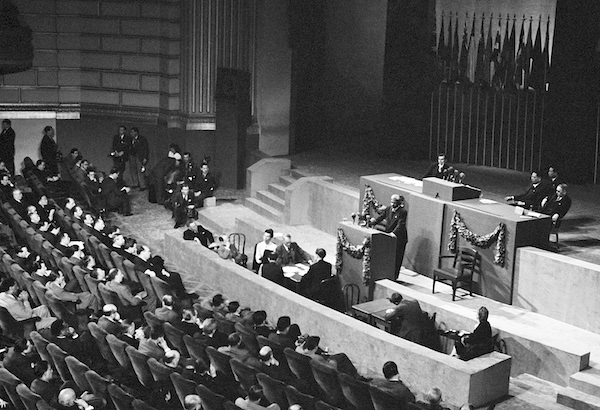

Sir. A. Ramaswami Mudaliar, Supply Member of the Governor General’s Executive Council, Leader of the Delegation from India, addresses the Third Plenary Session. T. V. Soong (China), on stage, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Chairman of the Delegation of the Republic of China presiding the Third Plenary Session, 25 April 1945, San Francisco.

Photo / Courtesy UN

The UN was conceptualized as a post-Second World War global governance structure, which would rest on three pillars: political, economic and human rights. The UN General Assembly (UNGA) would oversee the functioning of the political pillar of the UN, entrusted under the Charter to the UN Security Council (UNSC), while its socio-economic work, including upholding fundamental human rights and freedoms, would be handled by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

The intention of the countries creating the UN was to both “secure” and to “sustain” the peace that would come once the Second World War ended.

Sir A. Ramaswami Mudaliar, Supply Member of the Governor-General’s Executive Council; Leader of the delegation from India, signing the UN Charter at a ceremony held at the Veterans’ War Memorial Building on 26 June 1945. Sir V.T. Krishamachari, standing behind him, also signed the Charter on behalf of India’s Princely States.

Photo / Courtesy UN

The first structures to “sustain” the peace were created in July 1944 when 44 countries participated in the UN Financial and Monetary Conference held at Bretton Woods in the United States. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank) were established to coordinate a supportive role for monetary and development policies.

India played an active role in the negotiations at Bretton Woods. Sir C.D. Deshmukh and Sir R.K. Shanmukham Chetty, both of whom were to become Finance Ministers of independent India, were part of the Indian delegation. They are widely credited to have placed “poverty and development” into the mandate of the World Bank and secured for India permanent membership of the Executive Board of the IMF and World Bank because of her economic profile.

The eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly elected Madam Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, of India, as its first woman President. Madam Pandit is photographed here with U.N. Secretary – General Dag Hammarskjöld.

Photo / Courtesy UN

Between April and June 1945, India joined 49 other countries in negotiating the provisions of the San Francisco Treaty, known as the UN Charter. The leader of the Indian delegation Sir A. Ramaswami Mudaliar played a prominent role in chairing the discussions on economic and social issues to “sustain” the peace.

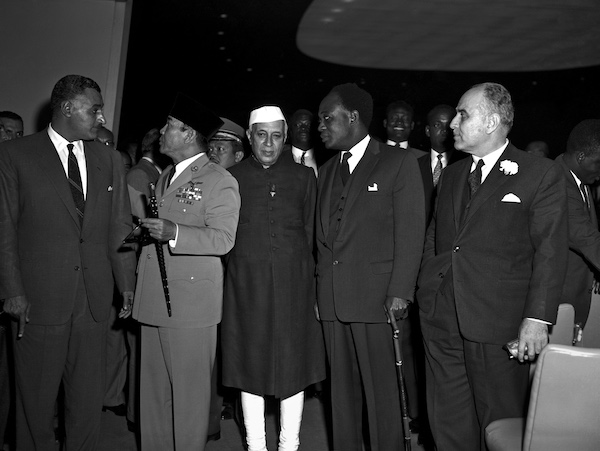

Leading statesmen from all over the world are attending the UN General Assembly. The historic Decolonization Resolution was adopted unanimously by the Assembly.

Seen here, left to right, are: Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of the United Arab Republic; Dr. Sukarno, President of the Republic of Indonesia; Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India; Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, President of the Republic of Ghana; and Mr. Saeb Salaam, President of the Council of Ministers of Lebanon.

Photo / Courtesy UN

The San Francisco Treaty (the UN Charter) was signed on 26 June 1945. India became the first country to be elected President of the ECOSOC in 1946. Under India’s presidency of the ECOSOC, several major initiatives were taken by the newly formed UN. These included the creation of regional UN bodies for coordinating socio-economic policies, such as the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). India was elected the first Executive Secretary of ESCAP from 1947-1956.

Among the significant initiatives taken under India’s Presidency of the ECOSOC for upholding fundamental human rights and freedoms, three stand out. The first was non-discrimination. In 1946, India successfully inscribed the need to abolish the discrimination based on color against Indians in South Africa, a UN member-state. This metamorphosed into the wider Anti-Apartheid Movement, which culminated with the successful multi-racial elections in South Africa in April 1994 and the election of President Nelson Mandela, who led South Africa’s delegation to the UNGA in September 1994. The second was the outlawing of mass atrocity crimes.

At a time of momentous change, the first summit-level meeting of the United Nations Security Council was held on 31 January 1992. The meeting reaffirmed the central role of the Security Council in maintaining world peace and upholding the principle of collective security as envisioned in the United Nations Charter. Attending the meeting were 13 Heads of State and Government, as well as two Foreign Ministers, representing the members of the Security Council.

Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao, Prime Minister of India, addressed members of the Council.

Photo / Courtesy UN

India joined Cuba and Panama to co-sponsor the 1946 UNGA resolution mandating the negotiation of the UN Genocide Convention in 1948. The third was gender equality. India’s delegate Hansa Mehta, who became the first Vice Chancellor of MS University in Baroda, successfully replaced the words “all men” by “all human beings” to expand the scope of the first UN document on human rights (the Universal Declaration on Human Rights) in 1948. Article 1 of the UDHR reads: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

The principle of democracy in international relations, contained in the provision of one-country one-vote in Article 18 of the UN Charter, was given substance following the independence of India in August 1947. Along with leaders of other newly independent former colonial countries, India spearheaded the unanimous adoption in December 1960 of the historic Decolonization Resolution in the UNGA, opening the doors for scores of newly independent countries to join the UNGA.

Shri Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, addresses the United Nations summit for the adoption of Agenda 2030 on Sustainable Development.

Photo / Courtesy UN

This resulted in a prominent Indian role in two platforms within the UNGA. The first was the political grouping of 24 member-states that created the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in September 1961. Today the NAM has 122 member-states in the UNGA. The second was the creation of the Group of 77 (G-77) developing countries in 1964, which turned the focus on accelerated development priorities as the focus of the UN and its ECOSOC. In turn, this led to the convergence of development issues with the growing concerns on environmental protection, which is today encapsulated in the ambitious UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development with its 17 Goals. The G-77 today has 134 out of the 193 member-states in the UNGA.

Eradication of poverty, articulated by India at Bretton Woods in 1944, is the over-arching Goal of Agenda 2030, which counts as a major achievement of the UN after 1945.

At the heart of India’s current and future engagement with the UN is the objective of “reformed multilateralism”. Essentially this means making the UN, its specialized agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), and sister institutions like the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization (WTO) more responsive to the challenges facing mankind.

An anomaly in the UN Charter has allowed decision-making without democratic participation. This anomaly gives the five militarily dominant powers of June 1945 (the Republic of China, France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union) permanent non-elected membership (P5) in the UN Security Council, and the privilege of the “veto”. The veto provision allows any of the P5 to oppose proposed UNSC decisions without giving any reason at all. This is an anachronism in 2020, and primarily responsible for the UNSC’s ineffectiveness today in maintaining international peace and security,

Since June 1945, the world has undergone a “surge to democracy”, illustrated by the membership of 193 member-states in the UNGA. As a British colony in June 1945, India had not been able to amend the UN Charter provision giving privileged powers to the P5. Those provisions had been agreed to before the San Francisco Conference by the United States, United Kingdom and Soviet Union at Yalta in February 1945. These privileges were extended to the Republic of China and France before the San Francisco Conference.

The key to reforming multilateralism lies in ensuring the equal and effective participation of member-states in decisions and policies that have a global impact. In the political sphere, this means reforming the UN Security Council to make it effective in “securing” the peace, by replacing its anti-democratic “veto” provision with majority voting using the one-country one-vote principle of the UN Charter. In the socio-economic sphere, this means closer coordination to ensure that monetary, development and human rights policies can sustain development.

To be effective, the scope of reformed multilateralism will have to expand beyond the narrow inter-governmental provisions of the UN Charter. It must also take cognizance of the rapid emergence of a digital world order. By including relevant stakeholders in global issues, including businesses, academia and civil society, reformed multilateralism would be able to provide a coherent and sustainable global response to global challenges. The UN is already moving towards such a “multi-stakeholder” structure through the implementation of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. This process needs to be reflected across the board to make the UN “fit for purpose”.

(The author is a former Indian diplomat and writer. He was Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations from April 2013 to December 2015)

Be the first to comment