A group of astronomers made over 100 routine observations of a distant ten-million-year-old star called HD166191 using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and combined that with knowledge about the star’s brightness and size to arrive at information that will help scientists test theories about how planets are formed and how they grow. Their findings are published in The Astrophysical Journal. The Spitzer Space Telescope was an infrared space telescope that was launched by NASA in 2003 and continued operating for sixteen years before it was finally decommissioned in 2019. Most rocky planets, satellites and other celestial objects in the solar system, including the Moon and the Earth, were formed by massive collisions early in the early history of the solar system. Terrestrial bodies accumulate more material and increase in size with these collisions. They can also break apart into many smaller bodies this way.

The astronomers, led by Kate Su of the University of Arizona, began making observations for HD 166191 in 2015. Around the star’s early life, dust left over from its formation has clumped together to form small rocky bodies called ‘planetesimals’, which are potentially seeds for future planets.

After the gas that had previously filled the space between these objects dispersed, catastrophic collisions between them became more frequent. The scientists began makings these observations using Spitzer between 2015 and 2019, anticipating that they might be able to gather evidence of such collisions.

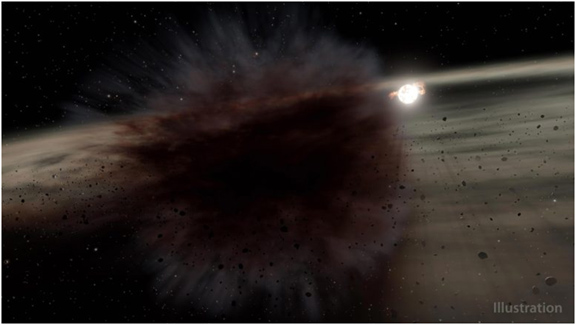

Even though the planetesimals themselves were too small to be captured by the telescope, their smashups produce large amounts of dust. As an infrared light telescope, Spitzer was uniquely suited to detecting the dust and debris created by these collisions.

Astronomers are able to record these observations by detecting when the debris cloud from one of these bodies passes in front of a star and briefly block light. This is called a transit.

In mid-2018, the HD 166191 system became significantly brighter for the Spitzer telescope, which suggests an increase in debris production. During the time, the telescope also detected a transit, or a debris cloud blocking the star.

The astronomers’ work suggests that this cloud is highly elongated with a minimum area estimated to be at least three times that of the star. However, the amount of infrared brightening detected probably means that only a small portion of the cloud passed in front of the star and that the debris from this event could even cover an area hundred times larger than that of the star. Source: The Indian Express

Be the first to comment