- Policy-making is easy. What’s difficult is the creation of physical and IT infrastructure

“Policy-making is the easy part. What’s difficult is the creation of physical and IT infrastructure. The hardest part is the task of making it work on the ground. The SFAC identifies and supports an IT expert (mandi analyst) for initial handholding for a period of one year for each mandi integrated with eNAM. They report to the state coordinator(s), each of whom handles the day-to-day coordination for 50 mandis each. They are also responsible for providing pro bono training to all stakeholders in the eNAM system: farmers, traders, commission agents and mandi officials.”

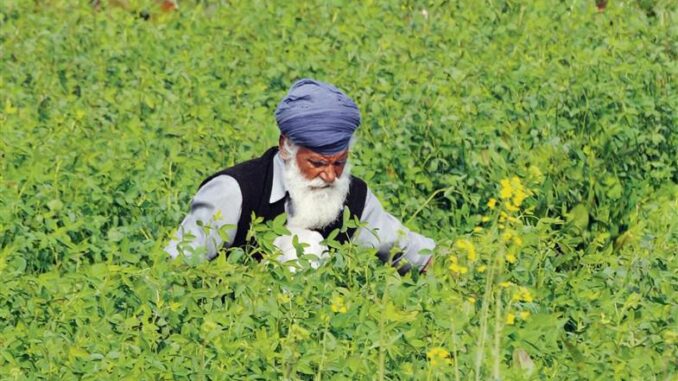

The recent bestowal of the Bharat Ratna on former Prime Ministers Charan Singh and PV Narasimha Rao and scientist-administrator Dr MS Swaminathan was a tribute to the entrepreneurial spirit of the Indian farmer. All three were deeply invested in and committed to agriculture as well as farmers’ welfare. Swaminathan’s contribution is well-known and acknowledged, but it is equally important to understand the political economy in which the Green Revolution was successful. It was Charan Singh who explained to Nehru the pitfalls of the Soviet and Chinese types of ‘collective farming’. He was clear that farmers were fiercely independent cultivators and were vehemently opposed to any centralized plan of ‘land pooling and cooperative farming’, which the Planning Commission was enamored of.

It was during Rao’s tenure that India joined the World Trade Organization and signed the Agreement on Agriculture. Till then, India’s policy regime had restricted imports. Under Rao, India looked to agri-exports as an important foreign exchange earner. With budgetary and institutional support to APEDA (Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority), he helped Indian agriculture become globally competitive, though domestic trade continued to be operated through restrictive trade practices that were good for the procurement agencies and registered traders of the Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), but not for the farmers.

Perhaps the most meaningful policy intervention made by him was the establishment of the Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium (SFAC) in 1994. The organization has now been tasked with the establishment of the national electronic market for agriculture. A transformative initiative was launched by PM Narendra Modi on April 14, 2016: the SFAC-backed Electronic National Agriculture Market (eNAM), a ‘phygital’ (physical plus digital) market. This is a single-window portal with a physical back end that provides actionable information, physical infrastructure, trade options and electronic settlement of payments.

Today, thanks to this initiative of the SFAC, 10.7 million farmers have the freedom, flexibility and facilities to transact across 1,389 regulated wholesale markets in 23 states and four union territories (UTs) in their own language on their mobile phones. Another 1.7 lakh integrated licenses have been issued by the participating states and UTs, but of even greater significance is the active participation of around 3,500 Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), for their transactions reflect granular support for this platform. As of January 2024, business of over Rs 3 lakh crore has been transacted on this platform.

It is imperative to share the backstory of this successful intervention. When the APMCs were introduced in the 1950s, the farmer needed protection against distress sale. The APMCs were designed to ensure ‘price discovery’ and provide a platform for procurement by state agencies under the MSP regime. However, in this process, they also created a special class of intermediaries: the trader who had a license to operate in the particular mandi with its notified command area.

However, as India became an IT superpower and agriculture moved from a peasant to a market mode of production, there was a need to change the restrictive rules of trade. Institutions like the SFAC were established to leverage technologies and financial instruments to improve the terms of trade for marginal and small farmers. From providing venture capital funds to agri-business entrepreneurs to the creation of infrastructure, the SFAC broke new ground in the establishment of FPOs, market intelligence, warehousing and procurement support. No wonder the mandate for the establishment of the eNAM was also given to the SFAC.

To set the ball rolling, the Agriculture Ministry gave a grant of Rs 30 lakh per mandi for equipment or infrastructure, such as computer hardware, Internet facilities and assaying equipment, among others, in those regulated mandis for the installation of the e-market platform. This was enhanced to Rs 75 lakh in 2017 for the creation of additional infrastructure like cleaning, grading and packaging facilities and a bio-composting unit. While in the first three years, about 200 mandis were brought under its purview, the pace picked up with 415 mandis by May 2020, another 260 by July 2022, yet another 101 by March 2023, and 28 by the end of the last calendar year. The number has been growing every quarter.

Policy-making is the easy part. What’s difficult is the creation of physical and IT infrastructure. The hardest part is the task of making it work on the ground. The SFAC identifies and supports an IT expert (mandi analyst) for initial handholding for a period of one year for each mandi integrated with eNAM. They report to the state coordinator(s), each of whom handles the day-to-day coordination for 50 mandis each. They are also responsible for providing pro bono training to all stakeholders in the eNAM system: farmers, traders, commission agents and mandi officials.

What next? Rather than rest on its laurels, the eNAM is setting newer and higher standards. Its revised mandate includes the expansion and consolidation of the eNAM by opening a platform beyond the APMC/Regulated Market Committee mandis to ensure competitive price realization for farmers. There is increased emphasis on warehouse-based sale and through eNAM. In the final analysis, it is price discovery and the freedom to sell that will usher in greater prosperity for the farmer.

(The author is Ex-Director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration)

Be the first to comment