In March 2007, President Musharraf suspended Chief Justice Iftakar Mohammed Chaudhry, accusing him of abuse of power and nepotism. Supporters of Chaudhry took the streets in protest, claiming the move was politically motivated. In May, 39 people were killed in Karachi when dueling rallies—those in support of Chaudhry and others of the government—turned violent. Justice Chaudhry had agreed to hear cases involving disappearances of people believed to have been detained by intelligence agencies and constitutional challenges involving Musharraf ’s continued rule as president and head of the military.

Chaudhry challenged his suspension in court, and in July, Pakistan’s Supreme Court ruled that President Musharraf acted illegally when he suspended Chaudhry. The court reinstated him. Radical Islamist clerics and students at Islamabad’s Red Mosque, who have been using kidnappings and violence in their campaign for the imposition of Shariah, or Islamic law, in Pakistan, exchanged gunfire with government troops in July 2007. After the initial violence, the military laid seige to the mosque, which held nearly 2,000 students. Several students escaped or surrendered to officials. The mosque’s senior cleric, Maulana Abdul Aziz was caught by officials when attempting to escape. After negotiations between government officials and mosque leaders failed, troops stormed the compound and killed Abdul Rashid Ghazi, who took over as chief of the mosque after the capture of Aziz, his brother.

More than 80 people died in the violence. Violence in remote tribal areas intensified after the raid. In addition, the Taliban rescinded the cease-fire signed in Sept. 2006, and a series of suicide bombings and attacks followed. Musharraf’s political troubles intensified in the late summer. In August, the Supreme Court ruled that former prime minister Nawaz Sharif could return to Pakistan from exile in Saudi Arabia. Both Sharif and Benazir Bhutto, also a former prime minister, had sought to challenge Musharraf’s role as military leader and president. Days after the ruling, Bhutto revealed that Musharraf had agreed to a power-sharing agreement, in which he would step down as army chief and run for reelection as president.

In exchange, Bhutto, who had been living in self-imposed exile for eight years, would be allowed to return to Pakistan and run for prime minister. Aides to Musharraf, however, denied that an agreement was reached. Shortly after, however, Musharraf said that if elected to a second term as president, he will step down from his post as army chief before taking the oath of office. Some opposition leaders, however, questioned whether he would follow through on his promise.

In September, Sharif was arrested and deported hours after he returned to Pakistan. On Oct. 6, Musharraf was easily reelected to a third term by the country’s national and provincial assemblies. The opposition boycotted the vote, however, and only representatives from the governing party participated in the election. In addition, the Supreme Court said the results will not be formalized until it rules whether Musharraf was constitutionally eligible to run for president while still head of the military.

The Return of Benazir Bhutto

Bhutto returned to Pakistan on Oct. 18 amid much fanfare and jubilation from her supporters. The triumphant mood gave way to panic when a suicide bomber attacked her convoy, killing as many as 135 people. Bhutto survived the attack. On Nov. 3, Musharraf declared a state of emergency, suspended Pakistan’s constitution, and fired Chief Justice Iftakar Mohammed Chaudhry and the other judges on the Supreme Court. In addition, police arrested at least 500 opposition figures. Political opponents said Musharraf had in effect declared martial law. Analysts suggested that Musharraf was trying to preempt an upcoming ruling by the Supreme Court, which was expected to declare he could not constitutionally run for president while head of the military. Musharraf, however, said he acted to stem a rising Islamist insurgency and to “preserve the democratic transition.” On Nov. 5, thousands of lawyers took to the streets to protest the emergency rule.

Many clashed with baton-wielding police. As many as 700 lawyers were arrested, including Chaudhry, who was placed under house arrest. Under pressure from U.S. officials, Musharraf said parliamentary elections would take place in Jan. 2008. On Nov. 9, thousands of police officers barricaded the city of Rawalpindi, the site of a protest planned by Bhutto. She was later placed under house arrest. On Nov. 15, the day that Parliament’s five-year term ended, Musharraf swore in a caretaker government, with Mohammedmian Soomro, the chairman of Pakistan’s senate, as prime minister. He also lifted Bhutto’s house arrest. Later that month, the Supreme Court, stacked with judges loyal to Musharraf, dismissed the case challenging the constitutionality of Musharraf being elected president while head of the military.

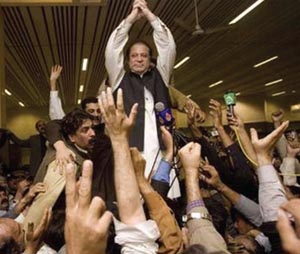

Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif returned to Pakistan on Nov. 25 after eight years in exile and demanded that Musharraf lift the emergency rule and reinstate the Supreme Court justices that were dismissed on Nov. 3. Sharif, who has refused to share power with Musharraf, poses a formidable political threat to Musharraf. Musharraf stepped down as military chief on Nov. 28, the day before being sworn in as a civilian president. Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the former head of Pakistan’s intelligence agency, Inter- Services Intelligence, took over as army chief.

Since he no longer controls the military, Musharraf’s power over Pakistan has been significantly diminished. Musharraf ended emergency rule on Dec. 14 and restored the constitution. At the same time, however, he issued several executive orders and constitutional amendments that precluded any legal challenges related to his actions during and after emergency rule and barred the judges whom he fired from resuming their positions. “Today I am feeling very happy that all the promises that I have made to the people, to the country, have been fulfilled,” he said.

Bhutto’s Assassination and Successor

Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in a suicide attack on Dec. 27, 2007, at a campaign rally in Rawalpindi. President Pervez Musharraf blamed al Qaeda for the attack, which killed 23 other people. Bhutto’s supporters, however, accused Musharraf’s government of orchestrating the combination bombing and shooting. Rioting throughout the country followed the attack, and the government shut down nearly all the country’s services to thwart further violence. Bhutto had criticized the government for failing to control militants who have been unleashing terrorist attacks throughout Pakistan. In the wake of the assassination, Musharraf postponed parliamentary elections, which had been scheduled for Jan. 8, 2008, until Feb. 18. Scotland Yard investigators reported in February 2008 that Bhutto died of an injury to her skull. They said she hit her head when the force of a suicide bomb tossed her. Bhutto’s supporters, however, insist she died of a bullet wound. Also in February, two Islamic militants who had been arrested in connection to the assassination admitted that they armed the attacker with a suicide vest and a pistol.

A New Government

In the parliamentary elections in February, Musharraf’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League-Q, which has been in power for five years, suffered a stunning defeat, losing most of its seats. The opposition Pakistan Peoples Party, which was led by Bhutto until her assassination and is now headed by her widow, Asif Ali Zardari, won 80 of the 242 contested seats. The Pakistan Muslim League-N, led by Sharif, took 66 seats. Musharraf party’s won just 40. His defeat was considered a protest of his attempts to rein in militants, his coziness with President Bush, and his dismissal of Supreme Court Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. The Pakistan People’s Party and the Pakistan Muslim League-N formed a coalition government.

In March, Parliament elected Fahmida Mirza as speaker. She is the first woman in Pakistan elected to the position. In March, Zardari selected Yousaf Raza Gillani, who served as speaker of Parliament in the 1990s under Benazir Bhutto, as prime minister. One of Gillani’s first moves as prime minister was to release the Supreme Court justices that Musharraf ousted and detained in late 2007.

The new government signaled a change of course with the announcement that it would negotiate with militants who live and train in Pakistan’s remote tribal areas. The policy met resistance from the United States, which, with approval from Musharraaf, has stepped up its attacks against the militants.

In May, the coalition government reached a compromise agreement to reinstate the Supreme Court justices who were dismissed in Nov. 2007 by Musharraf. The agreement fell apart days later, when the Pakistan Muslim League- N said it would withdraw from the cabinet because the Pakistan Peoples Party insisted on retaining the judges who replaced those who were dismissed by Musharraf. In addition, the two parties disagreed on how to reinstate the justices. Sharif wanted the judges immediately reinstated by executive order; Asif Ali Zardari, the leader of the Pakistan People’s Party preferred it be done through Parliament, a process that may be protracted.

Be the first to comment