Coinciding with 75 years of Independence, noted film critic Murtaza Ali Khan scanned for The Indian Panorama the 75 years of Indian Cinema. The article here will give readers a fairly good idea of the beginnings and the growth of Indian Cinema, the impact of government policies, the contribution of the Indian Diaspora, the influence of the NRI film makers, the difference the rise of web and the OTT platforms made to mainstream Indian Cinema, and the contribution of certain film makers. The author has also dwelt on the historical phases in the Indian cinema’s 75-year journey. Please send in your comments to murtaza.jmi@gmail.com – EDITOR

Storytelling is undeniably one of the most powerful tools known to mankind. It also happens to be one of the oldest art forms. Storytelling is not merely a means of indulgence but also a great source of learning. Since times immemorial, storytellers have spun yarns with the hope of delighting mankind. Be it the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer, the Jataka tales, the Mahabharata of Vyasa, the One Thousand and One Nights, or the plays of Shakespeare, each of these sprawling sagas, above all, has proven to be a consummate manifestation of the human expression. Storytelling shares an intimate relationship with performing arts. As far as India is concerned, the history of performing arts can be traced back to Bharatmuni’s Natya Shastra, which describes art as the search for truth. Human life too is a pursuit for truth and happiness. It is this connection that makes life and art inseparable. While discussing art in the context of the 20th and the 21st centuries, it is essential to explore cinema as a mass medium of storytelling that’s often looked upon as the definitive art form that seamlessly combines elements of storytelling, performing arts, and science.

Post-Independence, Indian cinema started evolving at a breakneck pace. While the film industry did suffer huge losses in terms of actors, writers, and technicians who decided to move to Pakistan, the industry greatly gained from the nation building campaigns helmed by Jawaharlal Nehru. For, many of these campaigns revolved around film stars whose mass appeal was leveraged upon by Nehru to give impetus to what came to be known as the Nehruvian idea of India. There is no denying that we have come a long way as a nation over the last 75 years: from bullock carts to jeeps to airplanes to space to the internet. As far as cinematic storytelling is concerned, OTT is the new buzz word, even as the jury is still out on whether cinema the way we know it would survive or not. So, let’s take a look at the journey of cinema since independence.

The origins of the cinematic medium

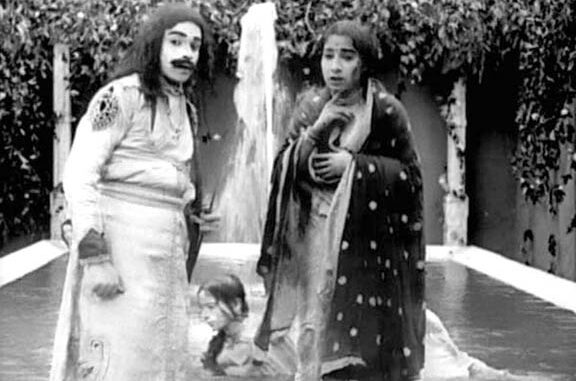

At the turn of the 19th century, cinema became a phenomenon across Europe thanks to the exploits of the Lumière brothers who conducted private screenings of projected motion pictures in the world’s major cities such as Paris, London, New York, Montreal, and Buenos Aires. It was in July 1896 that the Lumière films finally got screened in Bombay (now Mumbai). A couple of years later, an Indian photographer named Hiralal Sen made India’s first short film, A Dancing Scene, from the scenes of a stage show, The Flower of Persia. It was followed up by H S Bhatavdekar’s The Wrestlers (1899) – a recording of a wrestling match at the Hanging Gardens in Mumbai – which was also India’s first documentary film. In 1912, Dadasaheb Torne made a silent film titled Shree Pundalik – a photographic recording of a popular Marathi play.

A year later in 1913, Dadasaheb Phalke made India’s first feature-length motion picture – a silent film in Marathi titled Raja Harishchandra. Phalke, who is often referred to as the Father of Indian Cinema, had mastered the art of integrating centuries old narrative techniques, borrowed from the indigenous epics, with the emerging technique of making motion pictures. In 1916, R Nataraja Mudaliar made Keechaka Vadham, the first silent film in Tamil. Bangla motion pictures soon followed. The year 1931 proved to be a landmark for Indian cinema as it marked the end of the silent era with Ardeshir Irani making India’s first sound film Alam Ara, made in Hindi/Urdu.

Unfortunately, there is no surviving print of the same. And that’s what brings to me to this wonderful documentary by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur called Celluloid Man about the erstwhile director of the Nation Film Archive of India (NFAI), P K Nair who devoting his life collecting and preserving films. Of course, in the documentary we learn how Ardeshir Irani’s son disposed off the Alam Ara reels himself, after extracting silver from them. It would be due to the efforts of Nair that prints of Raja Harishchandra could be retrieved from Phalke’s daughter kept in Phalke’s Nasik house in a wooden box. Sometimes Nair world look for films in cowsheds and godowns. Of course, now we are becoming more aware about the importance of film preservation. The National Museum of Indian Cinema (NMIC) was inaugurated by the Indian Prime Minister. Narendra Modi on 19th January, 2019 at the Films Division Complex, Pedder Road, Mumbai.The Museum is open to the public from Tuesday to Sunday (11 AM to 6 PM) and is closed on Mondays and Public Holidays. It is housed in two buildings – the New Museum Building and the 19th century heritage building, Gulshan Mahal. The Museum showcases history of India Cinema and has ample artefacts, digital elements including kiosks, interactive digital screens, information-based screen interfaces, etc. It is frequently visited by leading personalities from the world of cinema. Film properties and costumes, vintage equipment, posters, copies of important films, promotional leaflets, soundtracks, trailers, transparencies, old cinema magazines, statistics covering film making & distribution etc. are displayed in a systematic manner depicting the history of Indian cinema in a chronological manner. NMIC not only provides a store house of information to the laymen, but also help filmmakers, students, enthusiasts and critics to know and evaluate the development of cinema as a medium of artistic expression.

Independence and further

On 15 August 1947 India became independent from the British Empire. The early commercial success of Phalke’s films not only paved the way for more such motion pictures but also set the ball rolling for cinema as a commercial art form. In the years to come, cinema in India evolved further as a potent art form capable of mirroring socio-political and economic issues plaguing India with films like Achhut Kanya (1936) and Sujata (1959). Hindi cinema gained international visibility with Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946) and Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953), which won the Grand Prix and Prix International awards at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946 and 1954, respectively.

Nehruvian socialism and post-independence Hindi cinema

National Award-winning film critic, M K Raghavendra, highlights in his book, The Politics of Hindi Cinema in the New Millennium: Bollywood and the Anglophone Indian Nation, how Hindi cinema, post-independence, played a big part in helping Indians imagine themselves as an entity binding them together – the Indian nation. Evidently, the first couple of decades after independence saw the influence of Nehruvian socialism on Hindi cinema. It is sometimes argued that popular films of the 1950s failed to capture the prevalent reality of the times owing to the filmmakers’ compulsion to fortify the nationalistic myths created by the newly appointed Jawaharlal Nehru government. However, if one tries to closely examine some of the most important films made during this period such as Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1951), Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953), Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957), and Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957), it becomes evident that the Hindi films of this period were not always in harmony with Nehru’s vision of India. But, it is also true that other important films from this era like Andaz (1949), Naya Daur (1957), and Howrah Bridge (1958) did succeed in depicting the dichotomy associated with Nehru’s ideals of modern India – the good side of modernity shown through the doctors, engineers, etc. and the bad side through the caricatures of the gamblers, cabaret dancers, etc.

Guru Dutt

Vasanth Kumar Shivashankar Padukone, better known as Guru Dutt, is lauded for his artistry, notably his usage of close-up shots, lighting, and depictions of melancholia. He is often referred to as the Orson Welles of Indian cinema. He directed a total of 8 Hindi films, several of which have gained a cult following internationally. This includes Pyaasa (1957), which made its way onto Time magazine’s 100 Greatest Movies list, as well as Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960), and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), all of which are frequently listed among the greatest films in Hindi cinema.

Raj Kapoor

Raj Kapoor is often described as the Charlie Chaplin of Indian cinema. He was greatly inspired by Charlie Chaplin and played characters based on The Tramp in films such as Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955). The song ‘Awara Hoon’ (which translates to I am a Vagabond/Tramp) from his movie Awaara becoming an anthem for protest against oppression in so many places across the globe: In China, in Soviet Union, In Middle East. It’s popularity led to creation of localized versions of the songs in Greece, Turkey, Romania, Soviet Union, and China. It is still considered a timeless song in South Asia, Balkans, Russia, and Central Asia.

Speaking of the leading ladies, Suraiya, Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Nargis, Wahida Rehman, Vyjayanthimala, Nanda, Nutan, Hema Malini, Rekha, Sridevi, Madhuri Dixit, Kajol, Aishwarya Rai, Vidya Balan, Deepika Padukone, Kangana Ranaut, and Alia Bhatt are amongst the most important Bollywood actresses to have graced the silver screen.

Indian cinema beyond Nehru

While these trends continued, Hindi cinema never eschewed from capturing the nerve of the important historical events in post-colonial India such as highlighting the gloomy reality of the Sino-Indian war, the euphoria associated with green revolution of the mid-1960s, Indira Gandhi’s meteoric rise in the late 1960s, her growing populism in the 1970s and her crushing defeat in the 1977 general elections following the 21 dark months of Emergency, emergence of regional conflicts during the 1980s like the Khalistan movement, and the economic liberalization during the early 1990s under the prime minister ship of P V Narasimha Rao, ushering in a new era of globalization.

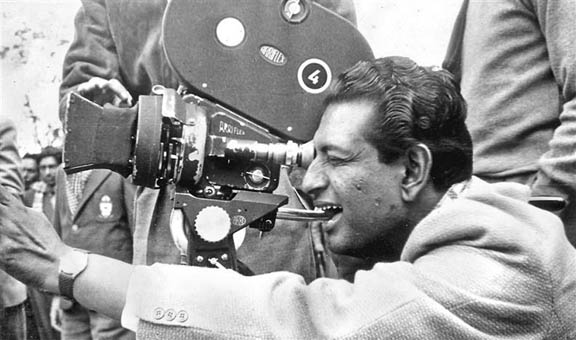

Satyajit Ray and Indian Neo-Realism

Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray, the father of Indian neo-realistic cinema, is widely regarded as one of the greatest auteurs of the 20th century. It wouldn’t be a hyperbole to call Satyajit Ray the most consummate filmmaker of all time, for when it came to the different aspects of filmmaking, he himself practically took care of everything: be it casting, scripting, direction, music, cinematography, art direction, editing, or marketing and publicity. An alumnus of Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan, Ray was born in a Calcutta based Bengali family noted for their long legacy of art and literature. It was in Santiniketan that Ray, under great painters like Nandalal Bose and Benode Behari Mukherjee, fell in love with the Oriental art. However, Satyajit Ray’s love for cinema and Indie filmmaking was sparked by his interaction with the legendary French filmmaker Jean Renoir who had come to Calcutta to scout locations for his forthcoming movie. After establishing Calcutta Film Society in 1947, Ray embarked on a six-month-long trip to Europe, as part of his job assignment in an advertising agency, during which he religiously explored the different facets of cinema, watching as many as 100 international films including Vittorio de Sica’s neorealistic masterpiece Bicycle Thieves (1948). Greatly inspired by the concept of realistic cinema that promoted a whole new degree of realism through the use of an amateur cast in place of a professionally trained one and real shooting locations instead of the custom-built sets and studios, Ray was more determined than ever to start a new chapter in Indian Cinema.

After facing many hardships including a major financial crunch, Ray finally managed to complete his adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhya’s celebrated novel Pather Panchali in 1955. The movie was presented with several international awards, including Best Human Documentary at the 1956 Cannes film festival. Just like Akira Kurosawa had managed with Rashomon in 1950, Ray succeeded in introducing the Indian Cinema to the whole world with Pather Panchali. Pather Panchali is the first part of Ray’s now world renowned The Apu Trilogy—the other two being Aparajito [The Unvanquished,1956] and Apur Sansar [The World of Apu, 1959]—that chronicles the troubled, poverty-stricken life (from childhood to maturity) of the movie’s protagonist, Apu, in the backdrop of the early 20th century Bengal. During the next few decades, Satyajit Ray continued with his merry ways making influential movies like Jalsaghar [The Music Room, 1958], Postmaster (1961), Abhijan [The Expedition, 1962], Mahanagar [The Big City, 1963], Charulata (1964), Days and Nights in the Forest (1969), and Pikoo [Pikoo’s Diary, Short, 1980] that dealt with the cultural, religious and socio-economic ambiguities of the Indian middle class. In the 70s, Ray went on to make the Calcutta trilogy: Pratidwandi [The Adversary, 1970], Seemabaddha [Company Limited, 1971] and Jana Aranya [The Middleman, 1975]. In 1977, Ray made his first Hindi film named Shatranj Ke Khiladi [The Chess Players], an adaptation of a story by the famous Hindi novelist Munshi Premchand. In 1980, Satyajit Ray made Hirok Rajar Deshe [The Kingdom of Diamonds], a political allegory written in the backdrop of Emergency to castigate the totalitarian political regime under Mrs. Indira Gandhi. During his long and illustrious career, Ray was a beneficiary of a multitude of meritorious awards, national and international, including the Bharat Ratna (Republic of India’s highest civilian award) and an Academy Honorary Award (an Oscar for his lifetime contribution to cinema) in 1992. Such has been the extent of influence of Ray’s multifaceted humanistic works that even today the global audience relates to the Indian Cinema mostly through the means of his oeuvre.

Ritwik Ghatak

Satyajit Ray’s contemporary, Ritwik Ghatak is best known for his films such as Nagarik (1952), Ajantrik (1955), Madhumati (1958), Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Subarnarekha (1965), and Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973), among others.

Ghatak’s cinema is primarily remembered for its meticulous depiction of social reality, partition and feminism. Ghatak moved briefly to Pune in 1966, where he taught at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). His students included filmmakers Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Adoor Gopalkrishnan, Saeed Akhtar Mirza, andJohn Abraham. Although his stint teaching film at FTII was brief, his students who would go on to become noted filmmaker themselves such as Mani Kaul, John Abraham, and especially Kumar Shahani, carried Ghatak’s ideas and theories, which were elaborated upon in his book ‘Cinema and I,’ which was described by Satyajit Ray as a book that covers all aspects of filmmaking. As opposed to Ray who succeeded in creating an audience outside India during their lifetime, Ghatak and his films were appreciated primarily within India. But, it has changed in the recent decades as Ghatak’s work continues to get discovered globally.

Mrinal Sen

Along with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen pioneered the parallel cinema movement in India, as a counterpoint to the mainstream fare of Hindi cinema. Sen’s cinema is primarily known for its artistic depiction of social reality.

Sen is one of the very few filmmakers to have won an award or recognition at all the major cinematic forums. In addition to a barrage of National Awards, Mrinal Sen’s immensely thought-provoking films have been recognized at Cannes Film Festival (Jury Prize for Kharij, 1983), Berlin International Film Festival (Grand Jury Prize for Akaler Sandhane, 1981), Venice Film Festival (Honourable Mention for Ek Din Achanak, 1989), Montreal World Film Festival (Special Prize of the Jury for Khandhar, 1984), Moscow International Film Festival (Silver Prize for Chorus, 1975), Cairo International Film Festival (Silver Pyramid for Best Director for Aamaar Bhuvan, 2002), Chicago International Film Festival (Gold Hugo for Khandhar, 1984), etc.

In 1981, the Government of India awarded him with the Padma Bhushan. In 1985, President Francois Mitterrand, the President of France awarded him the Commandeur de Ordre des Arts et des Lettres the highest civilian honor conferred by that country. In 2005, he was conferred with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award. In 2000, President Vladimir Putin of the Russian federation honored him with the Order of Friendship.

Regarded by many as Sen’s greatest film, Bhuvan Shome’s sardonic humor and its realistic depiction of rural India made it a landmark of Indian cinema. In his Calcutta trilogy, Sen explored the civil unrest in contemporary Calcutta through stylistic experiments and fragmented narratives. Sen examined middle-class morality in his films Ek Din Pratidin and Kharij.

A recipient of countless national and international film awards, Sen was instrumental in drawing youth to theatre as a member of the Indian People’s Theatre Association. Unlike his contemporaries, Sen succeeded in breaking the language barrier by making films in languages other than Bangla. Some of his prominent films are in Oriya and Telugu, as well as in Hindi. Sen is regarded as the pioneer of political cinema in India. Before Sen, filmmakers usually stayed away from politics, thinking it to be a taboo subject. But Sen never eschewed from depicting the unrest, angst and deprivation of the Indian society. And perhaps that’s what inspired his successors to make films heavily laced with socio-political commentary.

Tapan Sinha

Tapan Sinha was one of the most prominent Indian film directors of his time forming a legendary quartet with Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen. He was primarily a Bengali filmmaker who worked both in Hindi cinema and Bengali cinema, directing films like Kabuliwala (1957), Louha-Kapat, Sagina Mahato (1970), Apanjan (1968), Kshudhita Pashan and children’s film Safed Haathi (1978) and Aaj Ka Robinhood.

Amitabh Bachchan and the Rise of the Angry Young Man

While during the late ’60s and early ’70s Hindi cinema witnessed the dominance of romantic movies with actors like Dev Anand, Rajesh Khanna, Shashi Kapoor, Dharmendra and actresses like Sharmila Tagore and Asha Parekh becoming household names, by the mid-1970s a new kind of hero emerged who was not identified by his chocolate boy image but by his rugged machismo. Popularly described as the ‘Angry Young Man’, this new protagonist actually represented the anger and frustration of an entire generation exploited by those in power. For, this was a period of political, social, and economic upheaval in India with the issues of poverty, unemployment, and political violence plaguing the common man more than ever.

While Amitabh Bachchan made this character his own (with the grand success of films like Zanjeer, Deewaar, and Sholay) through the ’70s and the ’80s, actors like Anil Kapoor and Sunny Deol carried the mantle forward into the ’90s. The ’70s and ’80s also marked the advent of the Indian New Wave or Parallel Cinema with films like Ankur (1973), Nishant (1975), Manthan (1976), and Saaransh (1984). Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) is widely considered as the starting point of this movement. Shyam Benegal, Mani Kaul, Ketan Mehta, and Govind Nihalani are some of the prominent names of the Indian New Wave.

The ‘90s and the Khan Trio

The late ’80s and the ’90s witnessed commercial Hindi cinema go from strength to strength with blockbusters like Mr. India (1987), Tezaab (1988), Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Khiladi (1992), Darr (1993), Mohra (1994), Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994), Karan Arjun (1995), Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995), Raja Hindustani (1996), Dil To Pagal Hai (1997), Kuch Hota Hai (1998), Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha (1998), and Mann (1999) setting new box office records. Many of these films starred Anil Kapoor, Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, Akshay Kumar, Aamir Khan, Ajay Devgan, Madhuri Dixit, Karisma Kapoor, and Kajol.

At the turn of the 21st century, parallel cinema underwent a revival of sorts with the arrival of filmmakers like Ram Gopal Varma, Madhur Bhandarkar, and Anurag Kashyap, whose cinema mainly dealt with depiction of organized crime. The success of Satya (1998), Chandni Bar (2001), Company (2002), Black Friday (2004), and Sarkar (2005) proves beyond doubt the changing tastes of the Hindi film audiences during this phase.

The growing influence of the Indian Diaspora on Bollywood filmmakers

If we study Hindi cinema closely, we observe that the 1990s proved to be the tipping point with Nehruvian socialism making way for economic liberalization in India. As the Indian economy gradually opened up to the world, the Hindi cinema underwent an Anglicization of sorts owing to the growing influence of the Indian Diaspora – a trend that is best demonstrated by films like Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Pardes (1997), Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), and Namastey London (2007). During this period, Bollywood started catering more and more to the English-speaking Indians. The trend perpetuated with the multiplex boom.

Subsequently, filmmakers like Vishal Bhardwaj, Anurag Kashyap, and Tigmanshu Dhulia made efforts to bring about a change to this trend by making films such as Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola (2013), Gangs of Wasseypur (2012), Paan Singh Tomar (2012), etc.

Bollywood and the 100 Crore Club

During this phase, Hindi cinema continued to take new leaps in terms of revenue generation but there appeared to be a stagnation of sorts in terms of creative thinking. The success of a Hindi film started depending on whether it entered the ‘100 Crore Club’ or not. Even the most successful films would run only for a few weeks as opposed to the ‘Jubilee Era’, when success was measured in terms of the number of weeks a movie ran in the theatres: 25 weeks (Silver Jubilee), 50 weeks (Golden Jubilee), or 75 weeks (Platinum Jubilee).

Hindi cinema and the Hindi heartland

Building on the trend that was started by the likes of Anurag Kashyap, Tigmanshu Dhulia, Vishal Bhardwaj, and Aanand L. Rai, Hindi films subsequently started focusing consciously on stories based in the Hindi heartland. The diaspora no longer remained the primary target of Hindi filmmakers and as a result as the industry witnessed a surge in the number of films that are set in north-central India which enjoys a Hindi-speaking majority. But, a lot of the mainstream Hindi films since Lagaan (2001) seemed to lack the impetus needed to march in the global arena. It is true that there have been Hindi films like Miss Lovely (2012), Titli (2014), and Masaan (2015) which have made it to the Un Certain Regard Section at Cannes.

The rise of web and the OTT platforms

Speaking of the audiences, the rise of various OTT platforms has had a dramatic impact on the nature of content produced. Today, we have audiences with such diverse tastes that content creators are forced to create content targeted at different segments of audiences. The COVID-19 pandemic has further given a fillip to OTT platforms. With cinemas indefinitely shut down more and more viewers are forced to shift to one or more of these platforms for their daily dose of entertainment. This has also given rise to what is described as binge-watching. But before we try and examine this in detail, it is first important to decipher the nuances of binge-watching. For the uninitiated, binge-watching is a way of consuming content all in one go as opposed to consuming it in serialized weekly installments. It’s an effective way to watch plot-heavy shows. Now that we have a basic understanding of this novelty we will try and analyze its various aspects. For years cinema has been enjoying an undisputed status over its poor cousin television. While one agrees with the classification of cinema and television as two different mediums it cannot be denied that with the advent of new age content the line between the two is fast fading. In fact, today we can easily look at the majority of binge-worthy international television / web series as 8 or 10 hour films and that’s primarily because of the topnotch production values and the cinematic grammar associated with them.

The advent of streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime has given rise to Indian original shows like Delhi Crime, The Family Man, Special Ops, Sacred Games, Scam 1992, Rocket Boys, Mirzapur, Apharan ,Inside Edge, Panchayat, Undekhi, Aashram, and Kota Factory, among others. The rapid emergence of binge-worthy content is proving to be a real game changer for the Indian entertainment industry at large. This is in stark contrast to some of the daily soaps we have grown accustomed to watching on Indian television over the years. But there is an interesting flip side to this trend. Often the viewer is in such a hurry to finish off a season that he / she often ends up overlooking some important details. Perhaps, this is a price that most viewers are willing to pay.

The emergence of binge culture is not just impacting the end consumers it is also pushing the artists to expand their horizons. The rise of binge culture poses a big challenge for the artists to make themselves platform agnostic. Putting together an 8 to 10 hours of quality content for every season requires a different level of creative commitment. However, at the same time, it provides them with a wonderful opportunity to reinvent themselves as per the changing needs of time. Now, India’s entertainment industry has a great scope for embracing new trends, the rise of binge culture is bound to have a strong impact on cinema viewing in the longer run once normalcy returns post-pandemic. While the opinions surrounding binge culture may widely vary, even the staunchest critics wouldn’t deny that the rise of new platforms like Netflix has led to greater accessibility, reach, and creative freedom.

The contribution of NRI filmmakers to Indian cinema

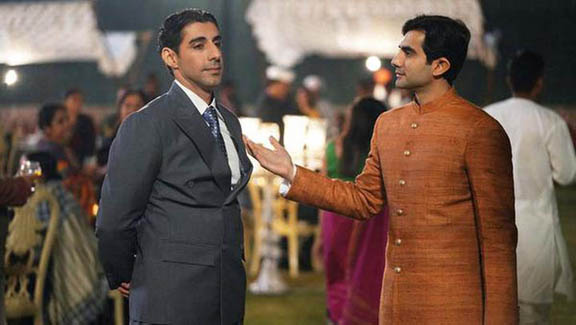

While discussing Indian cinema post-independence one would be remiss to overlook the contributions of NRI filmmakers whose multifaceted work offers a unique blend of cinema that binds the Indian Diaspora with the general populace. Emmy-nominated Indian-American filmmakerTirlok Malik is best known for making films about Indian immigrants in the US. Malik’s filmmaking journey started with his pioneering work Lonely in America (1990) which he wrote and produced while also acting in it. The film was shown in over 70 countries and screened at several leading festivals all across the globe. Since then he has made several other films about issues pertaining to the Indian diaspora such as Love Lust and Marriage, On Golden Years, and Khushiyaan which he shot in India with an ensemble cast that featured the likes of Jasbir Jassi, Tisca Chopra, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, and Rama Vij. Many internationally acclaimed filmmakers have also contributed wholeheartedly to the growth and development of Indian cinema in the global arena—most notably Mira Nair (Salaam Bombay!, Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love, Monsoon Wedding, The Namesake, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, A Suitable Boy), Deepa Mehta (Fire, Earth, Midnight’s Children, Leila), and Gurinder Chadha (Bend it Like Beckham, Bride and Prejudice, Viceroy’s House, Beecham House). Also, filmmakers Raj & DK deserve a special mention here as they too started their filmmaking journey outside India with their 2003 film Flavors about Indian immigrants living in America. In the recent years, Raj & DK have emerged as two of the most sought-after filmmakers in India. Their Amazon Prime Video web show The Family Man starring Manoj Bajpayee in the role of an Indian intelligence officer named Srikant Tiwari has emerged one of the most popular shows in the Indian web space.

The journey of Indian cinema since 1947 has had its share of ebbs and flows and the path forward is laden with difficulties and challenges. While there are opportunities galore, there are also many obstacles. Amit Khanna, the writer, director, and producer who has been an integral part of the Hindi film industry for the last five decades, recollects how he convinced his filmmaker friends to join him for a meeting he had set up with Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) during the early ‘90s which proved to be instrumental in helping Bollywood get an industry status. “After our studio system got dismantled around WWII, it took us almost five decades to once again get a little organized and corporatize things. I remember when I took my close friends such as Yash Chopra, Manmohan Shetty, Ramesh Sippy and others to a meeting with FICCI they all questioned the rationale behind it. Then over time the people realized the importance of the corporate connect. Back then I was the lone voice pushing for institutional financing and recognition as an industry. Through repeated representations with the government and relentless efforts we finally succeeded in securing the industry status that paved the way for the entry of the larger corporate players while some of the smaller ones also started getting institutionalized as funding became a lot more transparent,” explains Khanna who began his career as an executive producer with actor-producer Dev Anand’s Navketan Films in 1971. “In the ‘70s the video came in and kind of disturbed the equilibrium. There was a lot of resistance from producers and distributors against video. Also, there was a video piracy which continued well into the ‘80s. From a peak cinema screen count of 13,000 the number went down drastically by the ‘90s to less than 9,000. It was only towards the end of the 90s with the multiplex boom that things changed,” recollects Khanna.

Award-winning filmmaker and author Dr. Bhuvan Lall feels that the rich diversity that the Indian cinema continues to enjoy is seen nowhere else in the world. “A healthy cinema culture with regional flavors can only exist in a democratic setup where the artists are free to speak. India is a striking example of the largest producer of content on earth today. There is no denying that despite all the problems that we face as a country, our film industry is totally secular, totally based on Indian ethos, and capable of producing a vast array of content ranging from realism to fantasy. Here people love to say what they want to say. In any other country this is not possible as the population size doesn’t allow it. At the end of the day, you need to have a market for such diverse content and most countries in the world don’t enjoy the same luxury,” explains Lall.

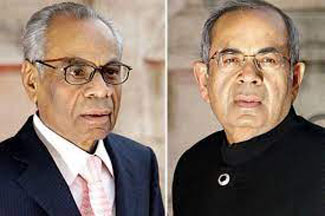

Noted Indian critic Ajit Rai, however,feels that European audiences need to know more about Indian cinema, especially beyond the works of Satyajit Ray. In the past, most of our commercial films to have tasted global success outside of the Indian Diaspora actually had a strong melodramatic appeal which greatly worked to their advantage,” opines Rai whose book on the Hinduja Family and the Indian Cinema titled ‘Hindujas and Bollywood,’ which tells the untold story of the global journey of over 1200 Hindi films as undertaken by the Hinduja brothers, starting with the 1950s, establishing Bollywood as a global brand, was launched in London, back in July 2022.

(Murtaza Ali Khan is an Indian Film & TV Critic / Journalist who has been covering the world of entertainment for over 10 years. He tweets at @MurtazaCritic and can be mailed at: murtaza.jmi@gmail.com).

Be the first to comment