The invasion was ostensibly on the specious ground of Saddam Hussein possessing weapons of mass destruction, based on conjectures and intelligent reports, in the face of men in the know pleading for patience. President Bush’s decision was part hubris, part spreading the credo of democracy, part a game changer in reordering the affairs of the Middle East.

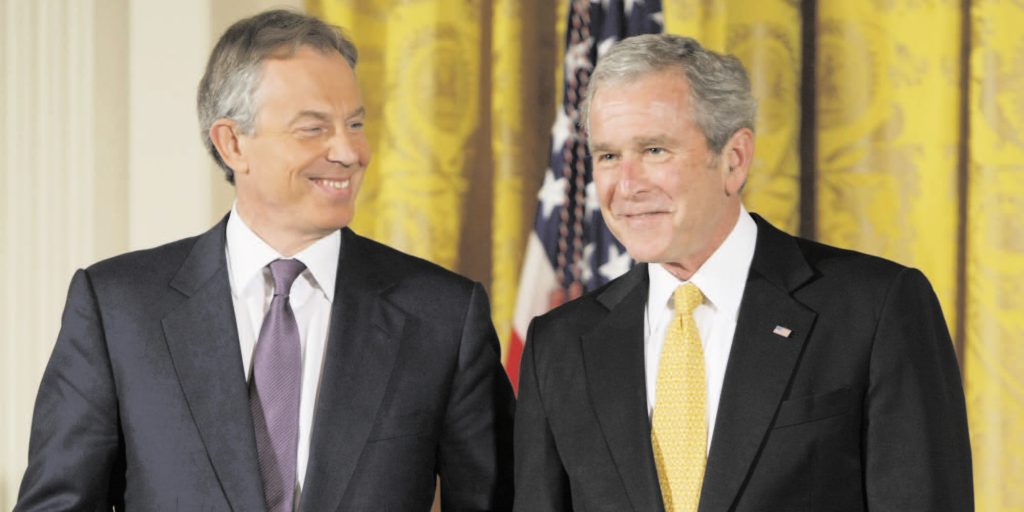

Mr. Blair was the enthusiastic young subaltern willing to do the President’s bidding, best summed up in the secret memo he sent the White House, now made public, months before the invasion saying. “I’ll be with you, whatever”. After the UK lost its empire in the post-World War II era, she ruled the world by proxy for decades as the pundit of US administrations in their negotiating the hot spots. But never has this subservient relationship been so frankly acknowledged as in Mr. Blair’s memo.

Britain, which has just made the fateful decision to leave the EU, is still searching for answers to its role in Europe and the world. In fact, the Brexit decision was born out of nostalgia for a lost empire, and in this contest between the heart and the head, the former won by a narrow margin.

Sir John’s was an inquiry into the British conduct in the Iraq invasion and war and the exhaustive report, which runs into several volumes, raps Mr. Blair’s conduct hard. But in a sense it is an even greater indictment of the conduct of President Bush who went to war on scant pickings without preparing for administering post-Saddam Iraq substituting bravado for policies on the ground.

Here lies the American tragedy on the use of unsurpassed power to remake the Middle East after a set of grandiose theories. The world knows how the crumbling Ottoman Empire was divided into spheres of influence between France and Britain 100 years ago in the shape of Sykes-Picot agreement. America entered the scene by appropriating the bulk of the rich oil flows and was happy to support monarchies and dictatorships.

The US had another interest, to protect Israel. What became known as the Israeli-American lobby and Washington’s geopolitical interests in propping up Israel meant that the usurpers of Palestinian land would never get justice. The Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement celebrated on the lawns of the White House suited Washington’s interests and was a partial one. And Israeli victories in wars with Arabs meant that what the victors won, they would keep. The two-state solution was a sop to Palestinians in the form of a toothless state now superseded by Mr. Benjamin Netanhayu’s relentless march for a Greater Israel.

To return to Iraq and Mr. Blair’s inglorious role in the invasion, the summary of the report presents a picture of his appropriating cabinet authority, declining to be bound by rigorous legal opinion and perhaps somewhat inebriated by his chummy relations with the occupant of the White House.

President Bush for his part was riding on his hobbyhorse of going down in history as the maker of a new map of the Middle East. And Paul Bremer, the man he appointed as first Governor of a defeated Iraq, totally misread the situation by excommunicating Saddam’s mainly Sunni army. In combination with the sectarian policies of Iraq’s Nouri al-Maliki, it was a priceless gift of well-trained officers and soldiers thrown into the arms of what became an insurgent force coalescing around the opposition, later to become the Islamic State.

Apart from the price Mr. Blair will have to pay for his role as Sancho Panza to Mr. Bush, the place Britain has come to occupy as America’s closest ally after the loss of empire needs re-examination. The British Parliament has learned to exercise some control over future military interventions by rejecting one of Prime Minister David Cameron’s military initiatives. But future policy makers must devise new trip wires before automatically following American military interventions. It would indeed appear that a redefinition of the responsibilities of ‘closest ally’ is called for.

Where does Britain go from here? To begin with, she has to cope with choosing a new prime minister before starting divorce proceedings with the EU, a Herculean task because she does not want to pay the full price for remaining in the single market by allowing the free movement and residency of EU nationals. Immigration was the emotive issue that won the Brexiters their double-edged victory.

Britons have been reluctant Europeans at the best of times. Now that they are in the process of reclaiming what they view as their full sovereignty, they need to carve out a new role in the new world order. The Japanese, for instance, are already worried that in their search for a role, they might indulge China in helping to rescind the embargo on high-technology arms exports.

Suggestions that Britain should revive the Commonwealth, a lame horse, are tantamount to barking up the wrong tree. The post-colonial experiment of leading ex-colonies in a totally different age is a non-starter. Those from the colonies who chose to settle in the UK -for instance, the large Indian diaspora -have their links with their original homes but these cannot be translated into a new grouping of political weight in the world. If the Modi government is thinking of playing a leading role in a revived Commonwealth, it would be set on a foolish venture.

The Chilcot report is a crunch moment for Britain because it illuminates the dilemmas of a once Great Britain that ruled the waves and countries far and wide. Having been reminded of the pitfalls of slavishly following the sole superpower, she has to begin to find a new direction.