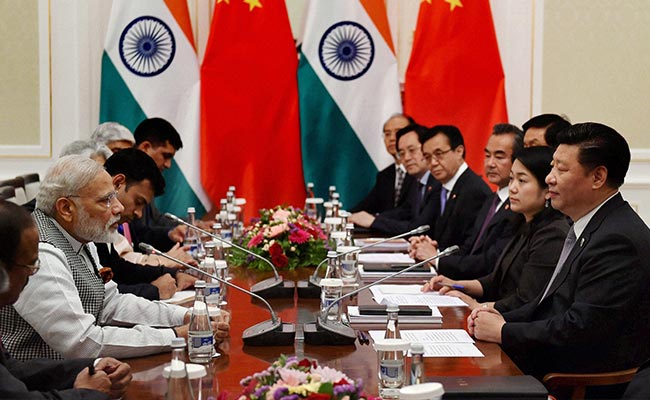

Photo courtesy PTI

On July 19, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman dropped his usual reticence to unilaterally comment on the escalating crisis within the Kashmir Valley, in which nearly 50 people have been killed in the violence so far following the death of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani.

“China has taken note of relevant reports. We are equally concerned about the casualties in the clash, and hope that the relevant incident will be handled properly,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang said in remarks posted on the Foreign Ministry website.

So as Chinese State Councillor and Special Representative on the Sino-Indian boundary dispute Yang Jiechi comes to Delhi next month to take forward the 20th round of talks with National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, both sides are hoping they will separate the ongoing bitterness from the business on the ground.

Photo courtesy PTI

Certainly, Delhi would like the Chinese to drop its objections to its application to become a member of the Nuclear Suppliers Group. The US has promised to hold a plenary meeting of the NSG to reconsider India’s application before the year is out, and Delhi doesn’t want the Chinese to play spoilsport again.

But the truth is that the Indian establishment still doesn’t fully understand the length to which the Chinese are prepared to go to deny India membership of the NSG. Not only does Beijing not want to see Delhi on the same page as itself, because it believes it is a much more powerful nation compared to India – certainly, its economy is five times larger – it also wants to be seen as a big power which is ready to shape the world in its own image.

In this image, Pakistan is not only a special friend and all-weather ally, it is also chief lackey.

Make no mistake, China’s refusal of India’s application at the NSG and its commentary on the Kashmir dispute are being made for two reasons. First, Beijing wants an acknowledgement that it is a ranking Asian power, and second, it wants India back on the same plane as Pakistan.

If the world has to hyphenate two Asian countries, believe the Chinese, the hyphenation has to be between India and Pakistan, not between Delhi and Beijing. The Americans are trying to sell India the latter dream, say Chinese analysts. They hope to debunk this as soon as possible.

That is why China is laying such store by “procedure” at the NSG – even when it is ready to trash the recent judgement of The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration which debunked Chinese claims to the South China Sea.

The need to be seen as a big maritime and land power is driving President Xi Jinping’s policy. Senior Chinese Communist party leaders such as the aforesaid Yang Jiechi and former state councilor in charge of foreign affairs in the Central Committee (and also a former Special Representative on the border talks) Dai Bingguo have been fielded in recent weeks to explain to worldwide audiences why Beijing will not abide by the Arbitration verdict in favor of the Philippines.

In fact, Beijing’s assertiveness has already frightened the Philippines and further divided ASEAN. Robert Duterte, recently elected President of the Philippines has said that he will walk back from the bitterness with China. Other ASEAN nations such as Laos and Cambodia are also willing to bend before China.

Even South Korea, a major non-NATO ally of the US, capitulated to China’s arms control negotiator Wang Qun at the NSG plenary in Seoul last month, when Wang insisted that procedure must be followed for new applications to the NSG, such as India’s.

Wang’s insistence that such “procedure” cannot be “discriminatory” means that either India must sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty – a demand that External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj rejected in parliament – or that Pakistan’s application to the NSG must also be accepted as the same time as India.

Certainly, the Chinese have recently begun to manifest a much tighter embrace with Pakistan. Islamabad has been an all-weather friend and ally for decades, but India was becoming a much larger economy, and China saw great advantages in pursuing greater opportunities for trade with India.

But over the last few years, China’s involvement in Pakistan’s economy has grown by leaps and bounds. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is an integral part of President Xi’s beloved One Belt, One Road project, and he has promised to invest as much as $46 billion in it.

At the same time, as Prime Minister Modi moved much closer to America – at last count becoming a major defense ally of the US – it seemed as if Delhi was joining hands with other democracies in the region to “contain” China.

On May 18, four ships of the Navy’s eastern fleet – including two guided-missile stealth frigates armed with supersonic anti-ship and land attack cruise missiles, a fleet tanker and a guided missile corvette – sailed towards the South China Sea and the North-Western Pacific for two and a half months. The deployment ended in June with the joint naval “Malabar” exercises off the coast of Okinawa in Japan (a US base is located there), in which the US Navy and Japanese self-defense forces also took part.

Certainly, China’s unusual commentary on Kashmir marks a new inflection point in its relations with India. One school of thought in Beijing believes that Delhi must learn to live with China’s rising power, including with the decision to build the CPEC through Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK). After all, this school says, India has learnt to live with the Karakoram Highway that was built in the 1970s, which also passes through PoK.

As China becomes more powerful, an ambitious faction in Communist Party circles has started believing that Beijing must get ready to play a bigger role in the resolution of the Kashmir dispute. Pakistan is already a good friend, says this school, and Aksai China is already controlled by China. Why not help resolve the Kashmir dispute too?

Of course, Beijing knows that any mention of Kashmir will be enough to rile the Indian government – especially when Pakistan marked yesterday as “Black Day,” in an effort to commemorate the crisis in the Valley.

As for Prime Minister Modi, he must be taught a lesson if he dares to believe that India can be equal to Asia’s foremost power. “This is China’s not-so-subtle way of putting India in its place,” said an observer of China, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

As Yang Jiechi wends his way to Delhi next month for boundary talks with Ajit Doval, the Indian side will certainly hope to have a heart-to-heart chat with him. It’s another matter whether or how much the Chinese leader will listen – or whether he will just smile softly as Xi Jinping did with Modi, when the latter asked him for support for India’s application to the NSG.

(The author, Jyoti Malhotra, is a freelance journalist with special passion for dialogue and debate across South Asia)

Be the first to comment