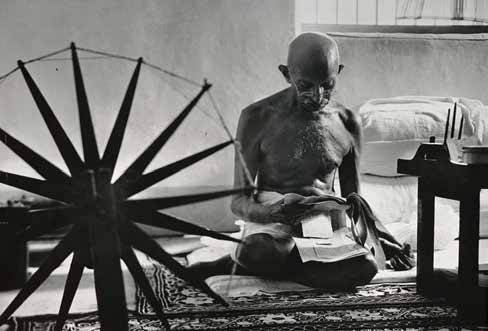

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, more commonly known as ‘Mahatma’ (meaning ‘Great Soul’) was born in Porbandar, Gujarat, in North West India, on 2nd October 1869, into a Hindu Modh family.

Gandhi Jayanti is a gazetted holiday in India on October 2 each year. It marks the anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth on October 2. Gandhi is remembered for his contributions towards the Indian freedom struggle.

Born into a privileged caste, Gandhi was fortunate to receive a comprehensive education, but proved a mediocre student. In May 1883, aged 13, Gandhi was married to Kasturba Makhanji, a girl also aged 13, through the arrangement of their respective parents, as is customary in India. Following his entry into Samaldas College, at the University of Bombay, she bore him the first of four sons, in 1888. Gandhi was unhappy at college, following his parent’s wishes to take the bar, and when he was offered the opportunity of furthering his studies overseas, at University College London, aged 18, he accepted with alacrity, starting there in September 1888.

Determined to adhere to Hindu principles, which included vegetarianism as well as alcohol and sexual abstinence, he found London restrictive initially, but once he had found kindred spirits he flourished, and pursued the philosophical study of religions, including Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism and others, having professed no particular interest in religion up until then. Following admission to the English Bar, and his return to India, he found work difficult to come by and, in 1893, accepted a year’s contract to work for an Indian firm in Natal, South Africa.

Although not yet enshrined in law, the system of ‘apartheid’ was very much in evidence in South Africa at the turn of the 20th century. Despite arriving on a year’s contract, Gandhi spent the next 21 years living in South Africa, and railed against the injustice of racial segregation. On one occasion he was thrown from a first class train carriage, despite being in possession of a valid ticket. Witnessing the racial bias experienced by his countrymen served as a catalyst for his later activism, and he attempted to fight segregation at all levels. He founded a political movement, known as the Natal Indian Congress, and developed his theoretical belief in non-violent civil protest into a tangible political stance, when he opposed the introduction of registration for all Indians, within South Africa, via non-cooperation with the relevant civic authorities.

On his return to India in 1916, Gandhi developed his practice of non-violent civic disobedience still further, raising awareness of oppressive practices in Bihar, in 1918, which saw the local populace oppressed by their largely British masters. He also encouraged oppressed villagers to improve their own circumstances, leading peaceful strikes and protests. His fame spread, and he became widely referred to as ‘Mahatma’ or ‘Great Soul’.

As his fame spread, so his political influence increased: by 1921 he was leading the Indian National Congress, and reorganising the party’s constitution around the principle of ‘Swaraj’, or complete political independence from the British. He also instigated a boycott of British goods and institutions, and his encouragement of mass civil disobedience led to his arrest, on 10th March 1922, and trial on sedition charges, for which he served 2 years, of a 6-year prison sentence.

The Indian National Congress began to splinter during his incarceration, and he remained largely out of the public eye following his release from prison in February 1924, returning four years later, in 1928, to campaign for the granting of ‘dominion status’ to India by the British. When the British introduced a tax on salt in 1930, he famously led a 250-mile march to the sea to collect his own salt. Recognising his political influence nationally, the British authorities were forced to negotiate various settlements with Gandhi over the following years, which resulted in the alleviation of poverty, granted status to the ‘untouchables’, enshrined rights for women, and led inexorably to Gandhi’s goal of ‘Swaraj’: political independence from Britain.

Gandhi suffered six known assassination attempts during the course of his life. The first attempt came on 25th June 1934, when he was in Pune delivering a speech, together with his wife, Kasturba. Travelling in a motorcade of two cars, they were in the second car, which was delayed by the appearance of a train at a railway level crossing, causing the two vehicles to separate. When the first vehicle arrived at the speech venue, a bomb was thrown at the car, which exploded and injured several people. No investigations were carried out at the time, and no arrests were made, although many attribute the attack to Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fundamentalist implacably opposed to Gandhi’s non-violent acceptance and tolerance of all religions, which he felt compromised the supremacy of the Hindu religion. Godse was the person responsible for the eventual assassination of Gandhi in January 1948, 14 years later.

During the first years of the Second World War, Gandhi’s mission to achieve independence from Britain reached its zenith: he saw no reason why Indians should fight for British sovereignty, in other parts of the world, when they were subjugated at home, which led to the worst instances of civil uprising under his direction, through his ‘Quit India’ movement. As a result, he was arrested on 9th August 1942, and held for two years at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. In February 1944, 3 months before his release, his wife Kasturbai died in the same prison.

May 1944, the time of his release from prison, saw the second attempt made on his life, this time certainly led by Nathuram Godse, although the attempt was fairly half-hearted. When word reached Godse that Gandhi was staying in a hill station near Pune, recovering from his prison ordeal, he organised a group of like-minded individuals who descended on the area, and mounted a vocal anti-Gandhi protest. When invited to speak to Gandhi, Godse declined, but he attended a prayer meeting later that day, where he rushed towards Gandhi, brandishing a dagger and shouting anti-Gandhi slogans. He was overpowered swiftly by fellow worshippers, and came nowhere near achieving his goal. Godse was not prosecuted at the time.

Four months later, in September 1944, Godse led a group of Hindu activist demonstrators who accosted Gandhi at a train station, on his return from political talks. Godse was again found to be in possession of a dagger that, although not drawn, was assumed to be the means by which he would again seek to assassinate Gandhi. It was officially regarded as the third assassination attempt, by the commission set up to investigate Gandhi’s death in 1948.

The British plan to partition what had been British-ruled India, into Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India, was vehemently opposed by Gandhi, who foresaw the problems that would result from the split. Nevertheless, the Congress Party ignored his concerns, and accepted the partition proposals put forward by the British.

The fourth attempt on Gandhi’s life took the form of a planned train derailment. On 29th June 1946, a train called the ‘Gandhi Special’, carrying him and his entourage, was derailed near Bombay, by means of boulders, which had been piled up on the tracks. Since the train was the only one scheduled at that time, it seems likely that the intended target of derailment was Gandhi himself. He was not injured in the accident. At a prayer meeting after the event Gandhi is quoted as saying:

“I have not hurt anybody nor do I consider anybody to be my enemy, I can’t understand why there are so many attempts on my life. Yesterday’s attempt on my life has failed. I will not die just yet; I aim to live till the age of 125.” Sadly, he had only eighteen months to live. Placed under increasing pressure, by his political contemporaries, to accept Partition as the only way to avoid civil war in India, Gandhi reluctantly concurred with its political necessity, and India celebrated its Independence Day on 15th August 1947. Keenly recognising the need for political unity, Gandhi spent the next few months working tirelessly for Hindu-Muslim peace, fearing the build-up of animosity between the two fledgling states, showing remarkable prescience, given the turbulence of their relationship over the following half-century.

Unfortunately, his efforts to unite the opposing forces proved his undoing. He championed the paying of restitution to Pakistan for lost territories, as outlined in the Partition agreement, which parties in India, fearing that Pakistan would use the payment as a means to build a war arsenal, had opposed. He began a fast in support of the payment, which Hindu radicals, Nathuram Godse among them, viewed as traitorous. When the political effect of his fast secured the payment to Pakistan, it secured with it the fifth attempt on his life.

On 20th January a gang of seven Hindu radicals, which included Nathuram Godse, gained access to Birla House, in Delhi, a venue at which Gandhi was due to give an address. One of the men, Madanla Pahwa, managed to gain access to the speaker’s podium, and planted a bomb, encased in a cotton ball, on the wall behind the podium. The plan was to explode the bomb during the speech, causing pandemonium, which would give two other gang members, Digambar Bagde and Shankar Kishtaiyya, an opportunity to shoot Gandhi, and escape in the ensuing chaos. The bomb exploded prematurely, before the conference was underway, and Madanla Pahwa was captured, while the others, including Godse, managed to escape.

Pahwa admitted the plot under interrogation, but Delhi police were unable to confirm the participation and whereabouts of Godse, although they did try to ascertain his whereabouts through the Bombay police.

After the failed attempt at Birla House, Nathuram Godse and another of the seven, Narayan Apte, returned to Pune, via Bombay, where they purchased a Beretta automatic pistol, before returning once more to Delhi.

On 30th January 1948, whilst Gandhi was on his way to a prayer meeting at Birla House in Delhi, Nathuram Godse managed to get close enough to him in the crowd to be able to shoot him three times in the chest, at point-blank range. Gandhi’s dying words were claimed to be “Hé Ram”, which translates as “Oh God”, although some witnesses claim he spoke no words at all.

When news of Gandhi’s death reached the various strongholds of Hindu radicalism, in Pune and other areas throughout India, there was reputedly celebration in the streets. Sweets were distributed publicly, as at a festival. The rest of the world was horrified by the death of a man nominated five times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Godse, who had made no attempt to flee following the assassination, and his co-conspirator, Narayan Apte, were both imprisoned until their trial on 8th November 1949. They were convicted of Gandhi’s killing, and both were executed, a week later, at Ambala Jail, on 15th November 1949. The supposed architect of the plot, a Hindu extremist named Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, was acquitted due to lack of evidence.

Gandhi was cremated as per Hindu custom, and his ashes are interred at the Aga Khan’s palace in Pune, the site of his incarceration in 1942, and the place his wife had also died.

Gandhi’s memorial bears the epigraph “Hé Ram” (“Oh God”) although there is no conclusive proof that he uttered these words before death.

Although Gandhi was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times, he never received it. In the year of his death, 1948, the Prize was not awarded, the stated reason being that “there was no suitable living candidate” that year.

Gandhi’s life and teachings have inspired many liberationists of the 20th Century, including Dr. Martin Luther King in the United States, Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko in South Africa, and Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar.

Be the first to comment