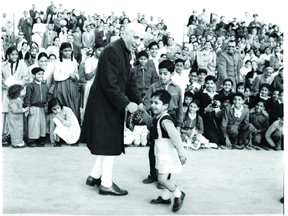

The birth anniversary of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, is celebrated as Children’s Day on November 14. A champion of children’s education and rights, Nehru was honored posthumously in 1964 when the government passed a resolution designating this day as Children’s Day. This act aimed to commemorate his significant contribution to the welfare of children in society.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India (1947–64), was born on November 14, 1889, in Allahabad, India. He established parliamentary government and became noted for his neutralist (nonaligned) policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of the Indian Independence Movement during the 1930s and ’40s.

Early years

Nehru was born to a family of Kashmiri Brahmans, noted for their administrative aptitude and scholarship, who had migrated to Delhi early in the 18th century. He was a son of Motilal Nehru, a renowned lawyer and leader of the Indian independence movement, who became one of Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi’s prominent associates. Jawaharlal was the eldest of four children, two of whom were girls. A sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, later became the first woman president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Until the age of 16, Nehru was educated at home by a series of English governesses and tutors. Only one of those—a part-Irish, part-Belgian theosophist, Ferdinand Brooks—appears to have made any impression on him. Jawaharlal also had a venerable Indian tutor who taught him Hindi and Sanskrit. In 1905 he went to Harrow, a leading English school, where he stayed for two years. Nehru’s academic career was in no way outstanding. From Harrow he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he spent three years earning an honours degree in natural science. On leaving Cambridge he qualified as a barrister after two years at the Inner Temple, London, where in his own words he passed his examinations “with neither glory nor ignominy.”

The seven years Nehru spent in England left him in a hazy half-world, at home neither in England nor in India. Some years later he wrote, “I have become a queer mixture of East and West, out of place everywhere, at home nowhere.” He went back to India to discover India. The contending pulls and pressures that his experience abroad were to exert on his personality were never completely resolved.

Four years after his return to India, in March 1916, Nehru married Kamala Kaul, who also came from a Kashmiri family that had settled in Delhi. Their only child, Indira Priyadarshini, was born in 1917; she would later (under her married name of Indira Gandhi) also serve (1966–77 and 1980–84) as prime minister of India. In addition, Indira’s son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded his mother as prime minister (1984–89).

Political apprenticeship

On his return to India, Nehru at first had tried to settle down as a lawyer. Unlike his father, however, he had only a desultory interest in his profession and did not relish either the practice of law or the company of lawyers. For that time he might be described, like many of his generation, as an instinctive nationalist who yearned for his country’s freedom, but, like most of his contemporaries, he had not formulated any precise ideas on how it could be achieved.

Nehru’s autobiography discloses his lively interest in Indian politics during the time he was studying abroad. His letters to his father over the same period reveal their common interest in India’s freedom. But not until father and son met Mahatma Gandhi and were persuaded to follow in his political footsteps did either of them develop any definite ideas on how freedom was to be attained. The quality in Gandhi that impressed the two Nehrus was his insistence on action. A wrong, Gandhi argued, should not only be condemned but be resisted. Earlier, Nehru and his father had been contemptuous of the run of contemporary Indian politicians, whose nationalism, with a few notable exceptions, consisted of interminable speeches and long-winded resolutions. Jawaharlal was also attracted by Gandhi’s insistence on fighting against British rule of India without fear or hate.

Nehru met Gandhi for the first time in 1916 at the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress (Congress Party) in Lucknow. Gandhi was 20 years his senior. Neither seems to have made any initially strong impression on the other. Gandhi makes no mention of Nehru in an autobiography he dictated while imprisoned in the early 1920s. The omission is understandable, since Nehru’s role in Indian politics was secondary until he was elected president of the Congress Party in 1929, when he presided over the historic session at Lahore (now in Pakistan) that proclaimed complete independence as India’s political goal. Until then the party’s objective had been dominion status.

Nehru’s close association with the Congress Party dates from 1919 in the immediate aftermath of World War I. That period saw an early wave of nationalist activity and governmental repression, which culminated in the Massacre of Amritsar in April 1919; according to an official report, 379 persons were killed (though other estimates were considerably higher), and at least 1,200 were wounded when the local British military commander ordered his troops to fire on a crowd of unarmed Indians assembled in an almost completely enclosed space in the city.

When, late in 1921, the prominent leaders and workers of the Congress Party were outlawed in some provinces, Nehru went to prison for the first time. Over the next 24 years he was to serve another eight periods of detention, the last and longest ending in June 1945, after an imprisonment of almost three years. In all, Nehru spent more than nine years in jail. Characteristically, he described his terms of incarceration as normal interludes in a life of abnormal political activity.

His political apprenticeship with the Congress Party lasted from 1919 to 1929. In 1923 he became general secretary of the party for two years, and he did so again in 1927 for another two years. His interests and duties took him on journeys over wide areas of India, particularly in his native United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh state), where his first exposure to the overwhelming poverty and degradation of the peasantry had a profound influence on his basic ideas for solving those vital problems. Though vaguely inclined toward socialism, Nehru’s radicalism had set in no definite mold. The watershed in his political and economic thinking was his tour of Europe and the Soviet Union during 1926–27. Nehru’s real interest in Marxism and his socialist pattern of thought stemmed from that tour, even though it did not appreciably increase his knowledge of communist theory and practice. His subsequent sojourns in prison enabled him to study Marxism in more depth. Interested in its ideas but repelled by some of its methods—such as the regimentation and the heresy hunts of the communists—he could never bring himself to accept Karl Marx’s writings as revealed scripture. Yet from then on, the yardstick of his economic thinking remained Marxist, adjusted, where necessary, to Indian conditions.

Struggle for Indian independence

After the Lahore session of 1929, Nehru emerged as the leader of the country’s intellectuals and youth. Gandhi had shrewdly elevated him to the presidency of the Congress Party over the heads of some of his seniors, hoping that Nehru would draw India’s youth—who at that time were gravitating toward extreme leftist causes—into the mainstream of the Congress movement. Gandhi also correctly calculated that, with added responsibility, Nehru himself would be inclined to keep to the middle way.

After his father’s death in 1931, Nehru moved into the inner councils of the Congress Party and became closer to Gandhi. Although Gandhi did not officially designate Nehru his political heir until 1942, the Indian populace as early as the mid-1930s saw in Nehru the natural successor to Gandhi. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact of March 1931, signed between Gandhi and the British viceroy, Lord Irwin (later Lord Halifax), signalized a truce between the two principal protagonists in India. It climaxed one of Gandhi’s more-effective civil disobedience movements, launched the year before as the Salt March, in the course of which Nehru had been arrested.

Hopes that the Gandhi-Irwin Pact would be the prelude to a more-relaxed period of Indo-British relations were not borne out; Lord Willingdon (who replaced Irwin as viceroy in 1931) jailed Gandhi in January 1932, shortly after Gandhi’s return from the second Round Table Conference in London. He was charged with attempting to mount another civil disobedience movement; Nehru was also arrested and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

The three Round Table Conferences in London, held to advance India’s progress to self-government, eventually resulted in the Government of India Act of 1935, which gave the Indian provinces a system of popular autonomous government. Ultimately, it provided for a federal system composed of the autonomous provinces and princely states. Although federation never came into being, provincial autonomy was implemented. During the mid-1930s Nehru was much concerned with developments in Europe, which seemed to be drifting toward another world war. He was in Europe early in 1936, visiting his ailing wife, shortly before she died in a sanitarium in Lausanne, Switzerland. Even at that time he emphasized that in the event of war India’s place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted that India could fight in support of Great Britain and France only as a free country.

When the elections following the introduction of provincial autonomy brought the Congress Party to power in a majority of the provinces, Nehru was faced with a dilemma. The Muslim League under Mohammed Ali Jinnah (who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls. Congress, therefore, unwisely rejected Jinnah’s plea for the formation of coalition Congress–Muslim League governments in some of the provinces, a decision that Nehru had supported. The subsequent clash between the Congress and the Muslim League hardened into a conflict between Hindus and Muslims that was ultimately to lead to the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

Jawaharlal Nehru: The Architect of Modern India

Jawaharlal Nehru was the first Prime Minister of independent India. One of the most prominent leaders of India’s Independent Movement, Pandit Nehru is known as the architect of modern India.

Pandit Nehru or Chacha Nehru as he was affectionately called was a nationalist leader, social democrat, author, and humanist.

Nehru was known for his vision, administrative aptitude, and scholastic prowess.

It was Jawaharlal Nehru who set out to realise the dream of a strong and resurgent India. He steered the nation to the path of recovery and modernisation. Nehru had neither the resources or the experience to administer the country. Yet, it was with his patriotism, dedication and commitment that he translated the values of the Congress into the Constitution of India.

It was Nehru who proposed the idea of fundamental rights and socio-economic equality irrespective of caste, creed, religion and gender. He invariably advocated the abolition of untouchability, right against exploitation, religious tolerance and secularism. He championed the idea of freedom of expression, right to form association, and was of the firm belief that statehood would ensure social and economic justice for labour and peasantry and give voting rights to all adult citizens. These propositions phrased by Jawaharlal Nehru made him the darling of India.

Here are some big decisions that nicknamed him an architect of modern India:

Establishing institutions of excellence

It was Nehru who provided the scientific base for India’s space supremacy and engineering excellence. With the establishment of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and universities, it was Nehru who put India on the path of development. Also, the foundation of the dual tack nuclear programme helped India achieve its nuclear enabled status. He also potentially set the pitch for industries, factories and the manufacturing sector paving the way for a journey of sovereign India.

Beginning of the Five-Year Plan

With his vision and deep understanding of the pulse of the nation, Nehru introduced the idea of a Five-Year Plan for effective and balanced utilisation of resources, something that India continues to benefit from. The First Five-Year Plan was introduced in 1951 when India, in the backdrop of the Partition, was faced with the influx of refugees, severe food shortage and sky-rocketing inflation. The FYP put the spotlight on agriculture, irrigation and development of the primary sector. The target GDP growth of the First Five-Year Plan was 2.1%, but the country recorded a growth of 3.6% that year under the stewardship of Nehru.

Institutionalising India’s democratic foundation

Nehru has always been seen as a true believer of democracy with a strong sense of institutionalisation of democracy where the concept of equal rights of citizens would take precedence over all societal divisions. India had just emerged from the shackles of a dictatorial British establishment and falling into the trappings of another ‘Mai-Baap Sarkar’ could have been a possibility. But Nehru laid up the foundation of a vibrant democratic establishment in India.

It was Nehru under whose regime the Election Commission of India, an autonomous constitutional body responsible for administering election processes in the country, was set up in accordance with the Constitution on January 25, 1950. The Election Commission of India conducted its first general election for the Lok Sabha which began in October 1951 and ended on till February 1952.

Making it the largest election held that time, around 173 million people cast their vote, no mean achievement as most of the voters were either uneducated or not familiar with the electoral system. Political leaders led by Nehru played pivotal roles in sensitising people and encouraging them to participate in the first Lok Sabha elections and exercise their franchise.

Shaping foreign policy

Pandit Nehru made indefatigable efforts to shape India’s foreign policy. As Prime Minister, Nehru held additional charge of the Ministry of External Affairs until his death. When India became independent, the world was recuperating from the calamitous World War II. It was a big challenge for Nehru to stitch relations with other countries amicably in the face of the changing power of balance in the United Nations.

Under Nehru’s guidance, India became the first country to adopt the Policy of Non-Alignment. The Asians Relations Conference was organised in Delhi in 1947, where India’s foreign policy was proclaimed. As many as 29 countries attended the conference which strengthened the solidarity of all Asian countries. India still benefits from the Nehruvian foreign policy. It is the country’s robust foreign policy that allows India to keep balance in maintaining foreign relations.

Nehru’s Panchsheel Agreement also served as the foundation for India-China relations. The Panchsheel Agreement was signed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai and adopted in December 11 1957. The essence of Panchsheel: To put the emphasis on peaceful co-existence and cooperation for mutual benefit.

India as welfare state

Pandit Nehru strongly advocated a welfare state— a blend between a capitalist and socialist system of governance. Nehru had travelled across the world and closely observed the working of various forms of governments that were in existence during that time. He witnessed the exploitation by capitalists during the time when colonialism was at its peak. Having meticulously gone through the pros and cons of the capitalist and communist systems of governance, Nehru came up with the idea of a ‘welfare state’ that India followed. A welfare state ideally provides basic economic security for its citizens by protecting them from market risks associated with unemployment, sickness and other risks connected with old age.

Be the first to comment