“The Trump administration has presented its plan for Afghanistan as a regional approach — it’s anything but that”, says the author.

“This is a continuation of the Obama administration’s policy. In 2015 and 2016, it had held back part of reimbursements to Pakistan from the Coalition Support Funds. Though Mr. Trump spoke tough on Pakistan, it is still unclear what could be the tough measures. Mr. White thinks overdoing this could be counterproductive: “Increased pressure is likely to push Pakistan into a corner, unlikely to deliver results in terms of cooperation on critical security issues. The insurgency in Afghanistan is largely organically funded. The safe havens help the Taliban, but I don’t think they are vital to the Taliban. So even if the pressure on Pakistan produces results, I don’t think its impact on the situation in Afghanistan will be significant.”

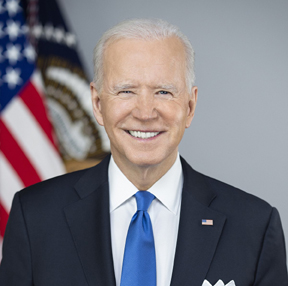

“The core goal of the U.S. must be to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat al-Qaeda and its safe havens in Pakistan, and to prevent their return to Pakistan or Afghanistan… And after years of mixed results, we will not, and cannot, provide a blank check (to Pakistan)… As President, my greatest responsibility is to protect the American people. We are not in Afghanistan to control that country or to dictate its future,” said the President of the United States, announcing a “regional strategy” for Afghanistan after the worst year of the conflict. The President was Barack Obama and the year was 2009.

On August 21, when President Donald Trump unveiled his new “regional strategy” for Afghanistan, it was in large part a reiteration of the above speech in terms of strategic objectives. By now 2016 has become the worst year of the conflict. Mr. Trump’s speech was high on rhetoric and low on detail. Three weeks later, do we know better? Interactions with people close to the subject, including Ahmad Daud Noorzai, head of the office of President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan, and Joshua White, who was Director for South Asian Affairs at Barack Obama’s National Security Council, provide some clues.

Junking timelines

Mr. Trump’s announcement of military commitment without a deadline in Afghanistan could be a game changer, both agree. “The word on the street is that Afghans are happy. This allows us to create a culture of peace, to build institutions and improve delivery of public services,” Ahmad Daud Noorzai, said during an interaction with a group of journalists and experts at the Afghanistan embassy in Washington last week. He said the most important reason for Afghanistan’s failure to stabilize has been the uncertainty around security.

Not announcing a timeline is wise strategy, feels Mr. White, who played a crucial role in President Obama’s Afghanistan strategy. “We examined the risk of drawdown and the outcomes looked ugly. Withdrawal would have been unwise. Significant scaling up of American troops would also have been unwise — that is the lesson that we learnt from the surge (in U.S. troop deployment in Afghanistan). We could not have fundamentally changed the balance of power without a large number of forces there forever,” he said in an interview at the Johns Hopkins University, where he teaches now (http://bit.ly/JoshuaTWhite).

Mr. Noorzai said Mr. Trump’s declaration that the U.S. would go after terrorists has already made a difference on the ground in Afghanistan: “From the military point of view, this is a huge change. This has already impacted the armed insurgents. When your commander-in-chief says to go after the terrorists, the nature of the military presence changes.” So more than the number of American boots on the ground, the nature and quality of America’s military presence has changed, and this could make a difference.

Pressure on Pakistan

The most tangible measure against Pakistan came a week after Mr. Trump’s speech as the administration decided to keep $255 million in military assistance to Pakistan in suspension until Islamabad demonstrates action against terrorist groups. This was earmarked in the U.S. budget for 2017. In July, Defense Secretary James Mattis did not provide certification that Pakistan was taking action against the Haqqani network, and held back $50 million from reimbursements to Pakistan for logistical support for the war in Afghanistan.

This is a continuation of the Obama administration’s policy. In 2015 and 2016, it had held back part of reimbursements to Pakistan from the Coalition Support Funds. Though Mr. Trump spoke tough on Pakistan, it is still unclear what could be the tough measures. Mr. White thinks overdoing this could be counterproductive: “Increased pressure is likely to push Pakistan into a corner, unlikely to deliver results in terms of cooperation on critical security issues. The insurgency in Afghanistan is largely organically funded. The safe havens help the Taliban, but I don’t think they are vital to the Taliban. So even if the pressure on Pakistan produces results, I don’t think its impact on the situation in Afghanistan will be significant.”

Mr. Noorzai said Mr. Ghani is trying to impress upon Pakistan to make the best use of Afghanistan’s economic potential: “We have excellent relations with the countries on the north, west and south. New trade routes and opportunities are opening up and Pakistan has a lot to gain from it all.”

Mr. Trump called upon India to play a larger role, but Washington’s expectations from India are very modest. No specific demand for monetary assistance has been made.

Expectations from India

The Trump administration, it appears, would like India to help in working with Afghanistan’s domestic factions in widening and buttressing the political legitimacy of the current government, and helping it improve its governance. For his part, Mr. Noorzai finds India’s increasing role in Afghanistan very welcome. “The Indian private sector must come to Afghanistan,” he said. “Start your business, make your profit. We could start with IT, we have so many needs. There is an impression in India that Indians are targeted in Afghanistan; Indians will need as much security as any other, but they can do their business. India needs to create a positive view in the country about Afghanistan so that the private sector understands the economic opportunity in Afghanistan.” Mr. White believes India has been self-restrained — “for good reasons” — in its role in Afghanistan, though from 2012 onwards the Obama administration was open to New Delhi playing any role that it could agree with the Afghan government. “There is value in signaling that the U.S. sees India as a critical partner for Afghanistan. But there is also a risk, because feeding Pakistan’s anxiety about Indian influence in Afghanistan is not necessarily helpful to either Washington or New Delhi,” he said.

Following Mr. Trump’s speech, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said India has a role to play in changing Pakistan’s behavior: “India and Pakistan, they have their own issues that they have to continue to work through, but I think there are areas where perhaps even India can take some steps of rapprochement to improve the stability within Pakistan and remove some of the reasons why they deal with these unstable elements inside their own country.”

Mr. White feels this is continuation of U.S. policy under President Obama: “The Trump administration has spoken more clearly and more directly about safe havens, not only for Afghan-focused groups but also for Indian-focused groups. But again, near the end of the Obama administration there were some strong statements and acknowledgment on that issue, particularly after the Uri attack.” He adds that America always wanted India to remain constantly engaged with Pakistan, “despite the disappointments India and the U.S.” had with Islamabad. There is an unmistakable level of continuity between the Obama and Trump administrations in viewing the India-Pakistan rivalry as a potential nuclear catastrophe. In fact, Mr. Trump mentioned that in his South Asia speech, and he has inherited the idea from the Obama era.

Not exactly regional

The Trump administration has presented the new strategy as a “regional” approach, but in the last three weeks it is clear that there is hardly any regional cooperation evolving or to be expected. Russia has termed the strategy a “dead end”, China has said Pakistan should be on board. The administration has acknowledged that Russia will work to undermine America in Afghanistan, but believes that China is interested in stability in Afghanistan. In June, the Pentagon’s half-yearly report on the situation in Afghanistan described India as “Afghanistan’s most reliable regional partner” and noted the interests — conflicting in many cases — of countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, China, Russia and the Central Asian states in Afghanistan, not to mention Pakistan. The new strategy does not appear to be addressing this factor and other measures of the Trump administration could aggravate the rivalries. Herein lies the most serious challenge in making any meaningful progress in Afghanistan.

(The author is a columnist with The Hindu)

Be the first to comment