Within three years, however, the BJP is huffing and puffing, tired of its own baggage of successes, whereas the much pilloried and humbled Congress is seen as rejuvenating like a fallen Arnold ‘Terminator’ Schwarzenegger being revived by his emergency batteries. If in the early 1960s, India faced the huge question mark, ‘Who, after Nehru?’, and in the 1970s, ‘Who, after Indira Gandhi? the year 2018 has arrived with ‘Who, after Modi?’

Bhagwat, who succeeded K S Sudarshan as the RSS chief in March 2009, has been junior to Modi in the Sangh Pariwar hierarchy and seen as the one unable to tame the man who now helms India from 7, Race Course Road in New Delhi. On the contrary, Bhagwat is seen as a Modi-acolyte and many of the RSS subsidiaries—the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM) etc.—have, from time to time, raised the standard of rebellion ostensibly against the Government’s failures to deliver on the promises and also, indirectly, against the Modi-Bhagwat stranglehold that may pull down the entire edifice built since the founding of the RSS in 1925. RSS is the “socio-cultural-spiritual” parent of the BJP, its political front, which is part of dozens of organizations having Hindutva ideological affinities with the Grand Master across India.

In 2014, when Narendra Modi, 64, became India’s 16th Prime Minister, he, and many, believed and boasted that he would continue to helm the affairs at least until 2024, what with the decimated main Opposition party, the Indian National Congress, touching the nadir of its entire political existence since 1885. Managing to win a measly 44 seats, out of 543, in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of Parliament), the corruption-accused, Jurassic Era’s Grand Old Party (GOP) had become laughing stock of the nation. Modi was the flavor of the season, the Knight-in-Shining-Armor, the Messiah…the very God Who Could Do No Wrong…

The ‘belief’ that the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by a ‘youthful’ and energetic Modi as the fulcrum of National Democratic Alliance (NDA), had finally arrived as an effective alternative to the Congress was further buttressed with the BJP winning a series of State Assembly elections across India, replacing the Congress everywhere. Indeed, a gloating Modi himself has been talking about how to make India celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of her Independence in 2022 and, hinting, how he will continue to helm India until 2024!

Within three years, however, the BJP is huffing and puffing, tired of its own baggage of successes, whereas the much pilloried and humbled Congress is seen as rejuvenating like a fallen Arnold ‘Terminator’ Schwarzenegger being revived by his emergency batteries. If in the early 1960s, India faced the huge question mark, ‘Who, after Nehru?’, and in the 1970s, ‘Who, after Indira Gandhi? the year 2018 has arrived with ‘Who, after Modi?’.

For, all these three towering leaders, suffering with narcissism, would leave no second line of leaders who could replace or succeed them—but Mother India has been fecund enough to nurture a successor silently, even if via transitional leaders until the NextGen was crowned. So, Lal Bahadur Shastri succeeded Nehru while Indira was by her son Rajiv Gandhi. The Mother could, therefore, be trusted to be silently nurturing a successor to Modi as well! Next year, 2019, he will face the Lok Sabha election with a heavy baggage from the past; and his possible successor, if he loses the elections, is not visible yet!

But why has this huge question mark emerged in the last few weeks? Has the Modi rhetoric run its course? Has his mystic and charisma seen a steep and sudden decline? Since 2014, he strode like a Colossus across not only India’s political firmament but also globally. He scripted many foreign policy firsts and successes, as millions of Indians looked with amazement at this fashion-designed Prime Minister making India proud both on national and global fronts. What has changed now, and so spectacularly?

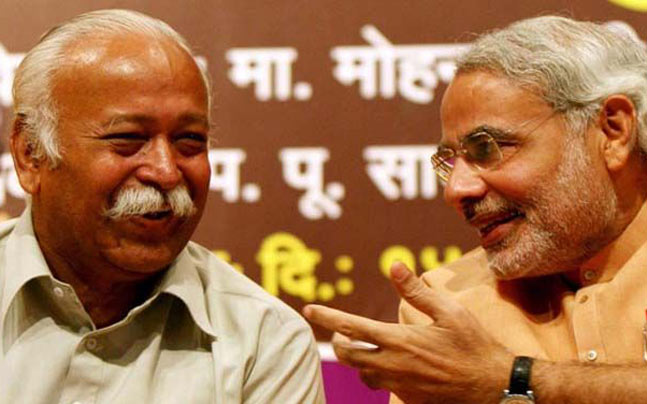

In November 2014, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat compared Modi with the Mahabharata’s Abhimanyu, Arjuna’s valiant son who knew how to enter a Chakravyuha (the enemy’s phalanx in concentric circles with openings only at opposite sides) but not how to come out of it, and was, therefore, slain by seven Kaurava warriors. Modi, buffeted as he is now encircled by seven enemies, may have stepped into Abhimanyu’s shoes!

His first enemy is, of course, the Indian economy. Only on January 5, the Central Statistical Organization (CSO) said the country’s growth in economy in 2017-18 slowed down to a four-year low of 6.5%, dragged down by sluggish manufacturing and farm sectors and the impact of the rollout of demonetization and Goods and Services Tax (GST) in the last one year. Clearly, an overall job-loss, farm distress shown by farmers’ suicides, youth unrest and the like have dragged down the people’s confidence in the government’s ability to deliver on its promises. Few, if any, are interested in what Moody’s says about Modi.

A year on, the double whammy of demonetization and GST have begun to impact politics. In Modi’s home state of Gujarat, the recent Assembly elections left the BJP with, at best, a pyrrhic victory with the saffron party winning only 99 of the 182 seats, lowest since 1995. This steep decline in Modi’s image emboldened the BJP’s own leaders to virtually blackmail the party leadership and extract their pound of flesh! Clearly, the Modi charisma began to fade, first of all, in his own state. Successful event managements, circus-like extravaganzas, and sound-and-light razzmatazz, all at the expense of the exchequer, cannot replace good politics!

His second enemy is India’s upwardly mobile and irreverent youth, nearly 100 million of them unemployed due to a variety of reasons. While battling for Prime Ministership in 2013-2014, Modi never tired of talking about this ‘demographic dividend’, what with 65% of the voters being in the 18-35-year age-group. He also drafted a series of plans for the youth, gave them dreams to live for and support him. But they remained pipedreams, and turned into nightmares for many. Empty promises disillusioned them, triggered youth rebellion, giving rise to the emergence of a formidable trio of Young Turks—Hardik Patel, Alpesh Thakore and Jignesh Mewani—in Modi’s own Gujarat. Together, they left the BJP with its bloodiest nose in 22 years and produced green-shoots in a Congress that lay comatose for a long time.

With these three youths, the caste-centric politics of the 1990s has returned to India. This return to India’s basic, chaotic politics is the third enemy of Modi, who seemed to have replaced the Mandal-Kamandal era of the BJP with his own brand of vikas-centric politics that sought to stress on socio-economic development. Due to lack of resources to fund development, his boastful brand of politics collapsed, first of all, in his home state of Gujarat in the December 2017 Assembly elections. The assertive-aspirational politics of the caste-conscious youth, soon, found expression in neighboring BJP-ruled Maharashtra where the Dalits (Suppressed Castes) raised a banner of rebellion against the Upper Castes, they saw as represented by the BJP’s Chief Minister Devendra Fadanavis.

Modi’s fourth enemy is the coming Assembly elections in eight states in 2018. Three of them are large states—Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh—and are BJP-ruled for years where the saffron party is expected to face a strong anti-incumbency and reverses. This is due to the BJP evolving itself as an ‘alternative’ to the Congress, i.e. as corrupt! The fourth state, Karnataka, hub of India’s IT revolution, also has little chances of going the BJP way. A caste-based social-re-engineering is now at work across the states and the “vote-banks” of yore are disintegrating everywhere, in the great socio-economic churning current in the cauldron called Modern India. Even the Muslims no longer remain a solid ‘vote-bank” as Muslim women saw in the ‘enemy’ BJP their emancipators, thanks to its support to them on the divorce issue, as evidenced in Gujarat by their large vote for the saffron party!

With these new emerging trends reshaping Indian politics, Modi’s fifth enemy is the likely revival of the erstwhile United Progressive Alliance (UPA), led by a revivified Congress under a combative Rahul Gandhi. If the BJP fails to win back the major states this year, and with one state slipping after another from the saffron fold, the NDA itself may come apart. Some of its current regional partners may even join the UPA bandwagon. Only a few months ago, the UPA seemed to be disintegrating what with Bihar’s Nitish Kumar joining the NDA; no longer. India’s politics has entered its most mercurial state and equations change quickly.

His sixth enemy is the overall disillusionment among the people with the political class as a whole. Modi came to power promising Achche Din (Better Days Ahead) and punishment to the corrupt UPA leaders but each one of them have been acquitted by the courts, and they are back hounding and howling at him. The general apathy of the voters for politicians of all hues, including Modi, was demonstrated by over 500,000 people who voted for the “None-Of-The-Above” (NOTA) option in Gujarat. This option, introduced by the Election Commission for the first time in an Assembly election, impacted the outcome in nearly 30 Assembly seats, out of 182, in Gujarat. It harmed both the BJP and the Congress as the number of NOTA votes were, in those 30 constituencies, more than the winning or losing margins.

And his seventh enemy is from within: the disgruntled Sangh Pariwar (Saffron Brotherhood) and its many constituents. In 2014, the entire Pariwar, with over 25 million workers, had helped Modi climb the steps of Raisina Hills in New Delhi and take oath as the Prime Minister of an aspirational India. Three years down the line, with few results to show on the ground, his promises galore remain hollow, his bravado seems melting away, his 56-inch chest losing muscle. His recent election speeches in Gujarat showed him as a tired titan. Promising a better future, he emerged from Bharat but surrendered to India.

But it is not Modi, the Abhimanyu, who alone may lose out. His “Krishna”, Mohan Bhagwat, having travelled with Modi so far and shielded him unconditionally, may also face heat from within the RSS rank-and-file for putting all the Hindutva eggs in Modi’s Nehru jacket.

Their relationship, to say the list, is interesting. Bhagwat, who succeeded K S Sudarshan as the RSS chief in March 2009, has been junior to Modi in the Sangh Pariwar hierarchy and seen as the one unable to tame the man who now helms India from 7, Race Course Road in New Delhi. On the contrary, Bhagwat is seen as a Modi-acolyte and many of the RSS subsidiaries—the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM) etc—have, from time to time, raised the standard of rebellion ostensibly against the Government’s failures to deliver on the promises and also, indirectly, against the Modi-Bhagwat stranglehold that may pull down the entire edifice built since the founding of the RSS in 1925. RSS is the “socio-cultural-spiritual” parent of the BJP, its political front, which is part of dozens of organizations having Hindutva ideological affinities with the Grand Master across India.

In a way, Modi himself may have undermined Bhagwat’s authority. In TV interviews, Modi had boasted in 2014 about his relations with Mohan’s father, Madhukar Rao, thus indirectly hinting that he (Modi) was senior to the Bhagwat Junior in the RSS hierarchy!

It is this internal dynamics of the RSS that helped bring Modi to power in 2014. And it is this internal dynamics of the RSS that may also defeat him at the hustings in 2019, what with most of the RSS workers remaining aloof from elections, as in Gujarat recently.

In 2014, the RSS had Modi to support. Who will it support in 2019?

(The author is a journalist since 1983 and has worked with newspapers, news agencies and magazines in English and Hindi languages. He has contributed articles on diverse subjects. Currently, he is working as Consulting Editor with Business Line, the business daily of The Hindu Group of Publications in India. He is based in Ahmedabad in Gujarat, India. He can be reached at virendra.pandit@gmail.com)

Be the first to comment