The media is being flooded with assessments of the Prime Minister’s “first year”in office. Has he taken the bull by the horns or has he been gored by an untamed beast?

Fashionable as these exercises are, they beg the question: What’s so sacrosanct about one year -come to think of it, nothing really. One year or birthdays are different according to the lunar and solar calendars, both prevalent in India. Then again, if you are born in a leap year, you have a longer stretch of time before your birthday arrives. And monarchs have their official birthdays. Leaving these complications aside, substantive issues plague us. Reforms the PM has promised can’t succeed or fail and be abandoned in a year. They can come in two forms, often complementing one another: Either they occur slowly but gather speed defined by the democratic process that sets up roadblocks identified centuries ago by Niccolo Machiavelli when he argued: “There’s nothing more difficult to take in hand… or more uncertain… than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things…The innovator has for enemies all those who’ve done well under the old conditions and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new.”

Today we say more pointedly that old ideas resulting in policies we wish to dismantle, now that our ideas have changed, run into difficulties as democratic leaders try to navigate around institutions built around old policies (the licensing system under the defunct brand of socialism) and interest (lobbies) that prospered under old policies (businessmen who enjoy monopoly rents in sheltered markets).

Thus, while PM Narasimha Rao and his FM Manmohan Singh understood reforms such as the defanging of the counterproductive industrial licensing system starting 1991, and opening of the economy to imports, they could only start a long-term process of reduction of trade barriers that went on for almost 15 years. Any hastening of that process would have led to a revolt by business lobbies and a reversal of the process: As policy economists say, if you try to kick a door open, it will likely rebound shut. So, as of today, Indian trade barriers have come down hugely: “Gradualism”worked where excessive speed would have undermined the reform.

So, we must give PM Modi full credit for the accretion of important reforms, steadily moving India in desired directions, since he assumed office. These include his reforms in the factor markets for labor and land, in each using the brilliant tactic of letting states initiate these reforms (just as Gujarat under his leadership used openness to trade and inward foreign investment to demonstrate their efficacy). Thus, MP and Rajasthan have undertaken important labor market reforms which should lead to diffusion through emulation of success.

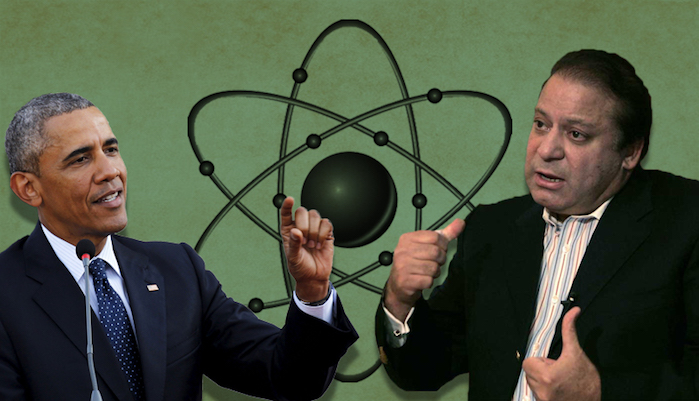

Modi has shown ingenious resilience using Ordinances to get around legislative obstructionism by the defeated Congress, especially in Rajya Sabha. This parallels President Obama’s resort to executive action to get around Republican obstructionism in the US Congress. While progressive constitutional lawyers in the US generally support Obama, some “committed”Indian constitutional lawyers fault the PM; but they’re best dismissed as ideologically blinkered.

The PM succeeded in turning the economic situation back from the brink where UPA II had led it, increasing social spending while the revenue intake had fallen. The resulting inflation, which hurt the poor, has been tamed. GDP growth has been turned around; and India is now regarded as a good prospect by investors.

The Economist had run a cover story about India in its February 2127, 2015 issue with the title: “India’s Chance to Fly”, correcting its earlier approach which had flown in the face of growing evidence that Modi would win and then indeed fly . Now, it seems, this illustrious magazine has regained its perspective and joins the many that see India as a growing economic success that may even better China‘s performance.

Despite the ill-informed ideological contention by left-wing Indians that Modi has enriched the rich and immiserized the poor, evidence shows that Indian poverty has declined significantly as growth accelerated after the 1991 reforms and the same is promised by the accentuation of these reforms since Modi took power.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Modi’s performance to date is on the social side. There has been no communal violence in his Gujarat in recent years when it was commonplace for decades; and the recent allegations that Modi and BJP were persecuting Christians has been exposed as a canard that was unfortunately bought into by unsuspecting Christians: a small minority that is much beloved in India, like the Parsis.

(Jagdish Bhagwati is a professor at Columbia University and Pravin Krishna is a professor at Johns Hopkins

University)

Be the first to comment