“But India-U.S. relations will be better off without hype and grand theories, often encouraged by the government. Otherwise, every rescheduling of a meeting will be interpreted as the collapse of ties. Similarly, avoiding the hyperbole could help manage India’s troubles with Pakistan and China better. The U.S. has overlapping interests with China, and India has overlapping interests with both. The trouble with big-chest, small-heart hyper-nationalism in foreign policy is that it also causes short sightedness. The audacity of hype has its limits.”

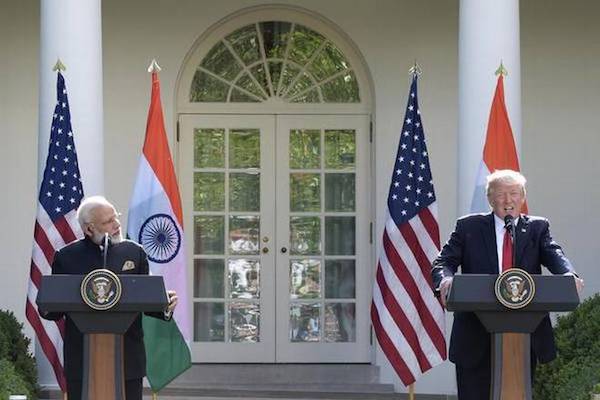

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and U.S. President Donald Trump have both built their politics on the promise of making their countries great again. Placing India and the U.S., respectively, as leaders on the world stage is the stated objective of their foreign policy. The project of regaining national glory is based on another assumption that they inherited a mess from their respective predecessors. Yet another shared trait is their love for spectacle over meticulous, prolonged and often frustrating pursuit of strategic goals.

Theatre as strategy

The postponement of the India-U.S. 2+2 dialogue between the Foreign and Defense Ministers of both countries, that had been scheduled for this week, has to be understood in the context of the similar personality traits of Mr. Trump and Mr. Modi. Hugging Mr. Trump may be a good spectacle for Mr. Modi, but the same may not be true for the former. Mr. Trump has set his eyes on spectacles that suit him. Mr. Trump, still basking in the denuclearization deal that he’s said to have struck with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, is now looking forward to the next big event: a summit meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin. His every move on the global stage enrages his domestic political opponents and the professional strategic community alike and he is happy, as this keeps his political base constantly on the boil.

North Korea, Syria, Afghanistan, trade deficit, and all global challenges before America are the faults of his predecessors, he repeatedly tells supporters. Most recently, at the G7 summit in Canada in June, he declared: “I blame our past leaders for allowing this to happen (trade deficits) …You can go back 50 years, frankly.” Such rhetoric may sound familiar to Indians. In Mr. Trump’s war on the legacy of all Presidents before him, India is on the wrong side. The remarkable growth in India-U.S. relations since the turn of the century had been nurtured by three U.S. Presidents, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, two Democrats and one Republican who have all been the target of Mr. Trump’s ire. India neither promises him the opportunity of a spectacle nor offers the grounds for destructing the legacy of a predecessor. So, he told Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to deal with North Korea and Russia, and 2+2 with India could wait. “Nobody wakes up in DC daily thinking of India,” says a former U.S. ambassador to India, pointing out that 16 months into the new administration, there is no Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia in the State Department.

Impact on ties

To buttress one’s own claim to be a trailblazer by denying the achievements of predecessors may be good political tactics for these leaders but trying to wish away history itself is not a sustainable strategy. Against the backdrop of a programmatic negation of history in both countries, Mr. Trump’s bursts of unhinged rhetoric against China and Pakistan lend themselves to easy and convenient interpretations by supporters of improved U.S.-India ties as moments of enlightenment for the U.S., even as turning points.

But Mr. Trump cannot undo all the legacy with a magic tweet. U.S. relations with Pakistan and China took shape during the Cold War. Pakistan might be the longest ally of the U.S. after the U.K., first in the fight against communism, and then in the fight against terror that was created in the first fight. China used the Cold War to its own advantage in its ties with the U.S.

China today threatens the dominance of the U.S., but the America’s security establishment and political elite are obsessed with Russia. India gets caught in that internal American fight too, such as in the case of an American law that now requires the President to impose sanctions on any country that has significant security relations with Russia.

Mr. Trump sees the challenges posed by China, but not in a manner helpful for India. For, India and China are in the same basket for Mr. Trump on many issues that agitate him. He has repeatedly mentioned India and China in the same breath as countries that duped his predecessors on climate and trade deals. His administration considers India and China as violators of intellectual property laws, as countries that put barriers to trade and subsidize exports and use state power to control markets. The nationalists in the Trump administration, including U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and White House National Trade Council Director Peter Navarro are all gunning for China, and India is in the same firing line. Many Americans who think that China took the U.S. for a ride — many Democrats among them — suspect that India is trying to do the same thing.

But there are two constituencies in the U.S. that promote India against China: the Pentagon and the U.S. arms industry. This works to India’s favor. While the Obama administration could not overcome State Department objections to offer India even unarmed drones, the Trump administration has done so, offering armed drones. Here, Mr. Trump is not guided by any grand theories of ‘rule-based order’, etc. that professional strategists talk about, but by the opportunity to sell.

Given Mr. Trump’s views on trade, American companies that used to argue China’s case are now guarded in their approach. Still, companies such as General Motors and Ford have come out against a trade war with China. This has implications for India too. American companies that eye the Indian market are allies in the pushback against Mr. Trump’s nationalist trade policies. Mr. Modi has realized this dynamic that puts India and China in the same corner in Mr. Trump’s perspective — and that significantly explains his Wuhan summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping, the third big leader who is gaming for the glory of his country.

War against legacy

The enlightenment that Mr. Trump purportedly brought on America’s Af-Pak policy also appears to have been short-lived. If one looks at the tough messages from Nikki Haley, U.S. Ambassador to the UN, in New Delhi recently on Pakistan and Iran, it is clear where the political priorities of the Trump administration lies. Here again, Mr. Trump is determined to gut his predecessor’s legacy, a key component of which was rapprochement with Iran. The war in Afghanistan is the worst optics for Mr. Trump’s showman politics, and his administration’s approach has been to sweep it under the carpet. The Pentagon has restricted release of data on the war, but a report last month paints a picture of a deteriorating situation. The U.S.’s ability to arm-twist Pakistan has been limited anyway, and Mr. Trump’s determination to turn the screws on Iran makes it tougher. National Security Adviser John Bolton, who had advocated bombing Iran, believes that a hardline policy against Pakistan is not desirable.

All told, Mr. Trump might accept Mr. Modi’s invitation to be the chief guest at the 2019 Republic Day parade just ahead of the Lok Sabha campaign, triggering another round of commentary on their ‘body language’ and ‘chemistry’. A series of significant defense purchases and agreements could be concluded in coming months. But India-U.S. relations will be better off without hype and grand theories, often encouraged by the government. Otherwise, every rescheduling of a meeting will be interpreted as the collapse of ties. Similarly, avoiding the hyperbole could help manage India’s troubles with Pakistan and China better. The U.S. has overlapping interests with China, and India has overlapping interests with both. The trouble with big-chest, small-heart hyper-nationalism in foreign policy is that it also causes short sightedness. The audacity of hype has its limits.

(The author is an assistant editor with The Hindu. He can be reached at varghese.g@thehindu.co.in)

(Source: The Hindu)

Be the first to comment