The Delhi High Court judgment convicting Sajjan Kumar reminds the country that it must not forget mass killings

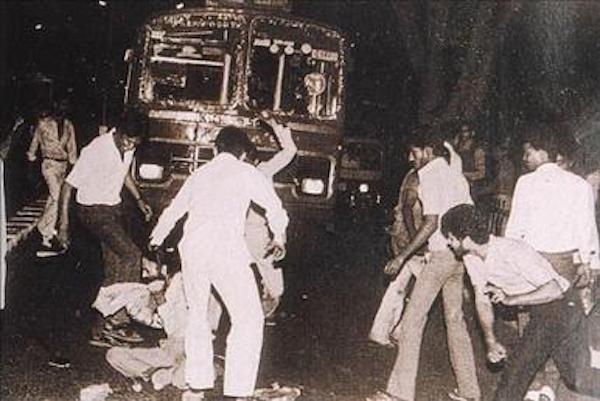

Thirty-four years after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and the killings of Sikhs that followed, a political leader who may have electorally benefitted from communal violence has been sentenced to imprisonment for life. The wheel of history has turned ever so slowly, as some believe, but its arc may have yet turned towards justice. The assassination of Indira Gandhi, on October 31, 1984, was a national tragedy. The anti-Sikh pogrom that followed in north India, with the worst violence taking place in Delhi, was a greater tragedy. But the greatest tragedy of all was the stonewalling of investigation by the law enforcement agencies, and the seeming deafness of the justice delivery system. The judgment reconstructs the scene of violence and all the waiting that followed.

Maze of inquiries

It took years of commissions of inquiry and other inquiries before six accused, including Sajjan Kumar, a formidable Congress leader in Delhi, who was a member of Parliament at the time, were sent up for trial sometime in 2010. Three years later, the trial court convicted five of the accused: three of them for the offences of armed rioting and murder, and two of them for the offence of armed rioting. Kumar stood acquitted by the trial court of all offences. Those convicted as well as the Central Bureau of Investigation appealed to the Delhi High Court. Now, the Bench of Justices S. Muralidhar and Vinod Goel has overturned the April 2013 judgment of the trial court and sent Kumar to prison for life. Their judgment carries the echo of the crimes committed in the days after Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination and failure to hold the guilty to account for so long.

The judgment finds: “The accused in this case have been brought to justice primarily on account of the courage and perseverance of three eyewitnesses. Jagdish Kaur whose husband, son and three cousins were the five killed; Jagsher Singh, another cousin of Jagdish Kaur, and Nirpreet Kaur who saw the Gurudwara being burnt down and her father being burnt alive by the raging mobs. It is only after the CBI entered the scene, that they were able to be assured and they spoke up. Admirably, they stuck firm to their truth at the trial.”

Staying the course

As a result of their testimony, Sajjan Kumar now stands convicted for conspiracy to murder and for the abetment of murder, in the deaths of Kehar Singh and his 18-year-old son Gurpreet Singh, and the killings of Raghuvinder Singh, Narender Pal Singh, and Kuldeep Singh — all members of the same family. I mention the names of the dead because the dead in communal violence should not lose their vestigial humanity by being simply reduced to a score of unnamed victims.

Kehar Singh’s wife, Jagdish Kaur, was one of the principal witnesses against Sajjan Kumar. The other principal witness is her cousin Jagsher Singh, whose brothers Raghuvinder and Narender Pal Singh were also killed on November 1, 1984. The high court judgment notes Jagdish Kaur’s recollection: “At around 9 am on 2nd November 1984, when she went to lodge a report at the PP, she saw that a public meeting was taking place which was attended by A-1 who was the local Member of Parliament (MP). She heard him declare, “Sikh sala ek nahin bachna chahiye, jo Hindu bhai unko sharan deta hai, uska ghar bhi jala do aur unko bhi maro.”

The judgment records Jagsher Singh’s recollection that “around 10 p.m., he saw an Ambassador car which stopped at the turning onto Shiv Mandir Marg. He stated that 30-40 persons gathered around the car from which emerged A-1 who enquired as to whether ‘they have done the work’. Thereafter, it is stated, A-1 approached the house of PW-6 (Jagsher Singh) to inspect it and came back and told the assembled mob that they had ‘only broken the gate of the thekedars’ house’. One of the members of the mob then allegedly informed him that ‘the thekedars are being saved by the Hindus only’. Upon hearing this, A-1 is stated to have instructed the mob to burn the houses of the Hindus who were sheltering the Sikhs. He then left in his car.”

The court rules: “To this Court, PW-1 [Jagdish Kaur] comes across as a fearless and truthful witness. Till she was absolutely certain that her making statements will serve a purpose, she did not come forward to do so. This is understandable given the fact that all previous attempts at securing justice for the victims had failed. The large number of acquittals in the cases demonstrated how the investigation was completely botched-up. It also demonstrated the power and influence of the accused and how witnesses could easily be won over. The atmosphere of distrust created as a result of these developments would have dissuaded the victims from coming forward to speak about what they knew. In the context of these cases, the factum of delay cannot be used to the advantage of the accused but would, in fact, explain the minor contradictions and inconsistencies in the statements of the key eye-witnesses in the present case. Nothing in the deposition of PW-1 points to either untruthfulness or unreliability. Her evidence deserves acceptance.”

A moment of reflection

Sajjan Kumar is not very different from many other politicians of this era, who use mob emotions to ride to power. However, he is probably the first to be held guilty of conspiring with the mob to cause the deaths of his constituents. It is for us as a country to ensure that mob violence yields no political dividends. If we as voters decide to electorally punish those who incite mobs, yield to them, or fail to stop their violence, the resort to politics of mass murders will simply stop. The judgment notes that “there has been a familiar pattern of mass killings in Mumbai in 1993, in Gujarat in 2002, in Kandhamal, Odisha in 2008, in Muzaffarnagar in U.P. in 2013 to name a few. Common to these mass crimes were the targeting of minorities and the attacks spearheaded by the dominant political actors being facilitated by the law enforcement agencies. The criminals responsible for the mass crimes have enjoyed political patronage and managed to evade prosecution and punishment.”

It also says: “While it is undeniable that it has taken over three decades to bring the accused in this case to justice, and that our criminal justice system stands severely tested in that process, it is essential, in a democracy governed by the rule of law to be able to call out those responsible for such mass crimes. It is important to assure those countless victims waiting patiently that despite the challenges, truth will prevail and justice will be done.”

While the 1984, 1993, 2002, 2008 and 2013 riots are painful episodes in our history, the judgments of the Delhi High Court of 2018 in the Sajjan Kumar and Hashimpura cases shine like good deeds in a naughty world. Milan Kundera wrote that “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting”. The judgment tells Kehar Singh, Gurpreet Singh, Raghuvinder Singh, Narender Pal Singh and Kuldeep Singh, that neither Jagdish Kaur nor India have as yet forgotten them.

(The author is a senior advocate of the Supreme Court)

(Source: The Hindu)

Be the first to comment