Vinoba Bhave said, ” We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors so we can see much further than they saw, not be limited by their limitations.”

Chaturvedi said the most appealing explanation he found for this transition was in the thoughts of Vinoba Bhave, MK Gandhi’s spiritual successor. A Sanskrit scholar who trusted his own reading over any rhetoric, Bhave was a complex figure, an ascetic with a fine aesthetic sense; one of modern India‘s least understood leaders.

“Several scholars have shown how the existing Hindu identity – or at least a significant part of it -draws from the colonial encounter. So, while some groups in India have eaten meat and beef since forever, the values of vegetarianism, non-violence and cow veneration have also been common”, says the author.

In 1979, Bhave sat on a fast, demanding a ban on cow slaughter in Kerala and West Bengal, perpetrating a political crisis for the Morarji Desai government. (In fact, the satyagraha Bhave began became India’s longest-running fast, ending only recently after the Maharashtra government banned cow slaughter in the state.) Yet, in his speeches, he made it clear that if tractors kept rolling in, people should prepare to slaughter bullocks and eat them.

Bhave’s most striking observation, Chaturvedi stressed, was his frank acknowledgement that ancient Sanskrit texts mention the eating of beef. So I pulled out my copy of Bhave’s Gita-Pravachan and found the section where he says we should not be surprised when we find out that some ancient rishis ate beef and meat was commonly eaten in India. He maintained it is a sign of evolution that such a large population accepted non-violence and turned vegetarian. Bhave said, “we stand on the shoulders of our ancestors so we can see much further than they saw, not be limited by their limitations.”

I have looked for years, and not met any cow protection activists with the courage to accept the uncomfortable truth with such courage. They tend to emphasize only their reading of the Vedas, determined to bring back the Golden Vedic Age through cow protection. Which alienates me.

My upbringing in a Hindu family has exposed me to the Gita and the Ramcharitmanas and the Bhagwat Puran, but never to the Vedas. When they need recourse to faith, most Hindus draw upon the devotional poetry of Tulsidas, Gyaneshwar, Meerabai, Raheem and scores of others; they do not chant verses from the Rigveda. In fact, ‘Vediya Dhor’ is an old term in folk culture to mock the carrier of Vedic knowledge as a beast of burden. The Vedic figure of Indra attracts little devotion, even as his nemesis Krishna is perhaps the most popular Hindu god.

A summary for those not familiar with the story from the Bhagwat Puran: the boy Krishna stops his father from making sacrificial offerings to Indra. The god of rain gets angry and sends down a seven-day-seven-night deluge, causing a flood. Krishna lifts the Govardhan hill as refuge from the flood. Indra is humiliated. The story is as much about appreciating nature and ecology over and above a tyrannical god, as it is a lesson in karma-yog, which is explained in greater detail in the Gita.

“Laws against cow slaughter will only criminalize the livestock trade, not protect the animals, said Ghotge. Only the smugglers and the law enforcement officials will benefit from the ban on cow slaughter, not the poor farmers or the livestock. Like the agriculture scientist Ramanjaneyulu, Ghotge holds that the cow protection laws are unjust; it is about powerful urban people outsourcing the burden of cow protection on the rural poor.”

I noticed even at a young age that the term ‘Hindu’ doesn’t occur in any religious text. Several scholars have shown how the existing Hindu identity – or at least a significant part of it – draws from the colonial encounter. So, while some groups in India have eaten meat and beef since forever, the values of vegetarianism, non-violence and cow veneration have also been common – and not just in one or two caste groups, either. Despite the practice of sacrificing animals coming down sharply in the past century or so, several Hindus in India and Nepal still practice the rites of Bali, most prominently during the festival of Gadhimai and at the Kamakhya temple in Assam.

This co-existence of meat-eating and vegetarianism is unique to India. How did this happen? In his Indian Food: A Historical Companion, after several pages describing meats eaten in India, Achaya explored the roots of vegetarianism and the beef taboo. He referred to the “sheer abundance and wide range of foodstuffs available even from Harappan times that could fashion vegetarian meals of high nutritional quality, and gustatory and aesthetic appeal. It is perhaps no exaggeration to say that nowhere else in the world except in India would it have even been possible to be a vegetarian in 1000 BC.”

Then I stumbled into a remarkable book: The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India. First published in German in 1962, its English translation appeared in 2010. The author, German Indologist Ludwig Alsdorf, had spent several years studying Jainism, and is regarded the first man to apply the historical method to the vegetarianism question. While it extensively deals with material that Jha also uses, Alsdorf’s writing is free of polemics.

Vegetarianism and cow-veneration are not directly related in history, neither was vegetarianism the basis of ahimsa (non-violence) to begin with, Alsdorf wrote. The idea of non-violence predates Jainism and Buddhism, even if it was the two movements that really made it popular in the face of Vedic sacrificial rituals. For example, it is believed that the ritual offering of coconut smeared with vermilion is a substitute for the severed head of an animal or even a human sacrificed at the altar; even Achaya refers to it. Which points to what Vinoba Bhave said about accepting our gory past.

The Buddha was against ritual sacrifice of animals, but not against consumption of meat. His instruction to his monks was that no animal should be killed to feed them; but they were allowed to eat any food they received in alms, including meat. It is widely understood that the Buddha had consumed pork before he died. Yet the origin of vegetarianism and cow-veneration may never get elucidated by available sources, Alsdorf concluded: “For the Indologist, it is indeed not a new experience that the pursuit of pressing problems in the present leads him back to the dim and distant past.”

The father of the ideology of Hindutva, Vinayak Damodar ‘Veer’ Savarkar, had a complex position on cow protection and cow worship. He saw cow protection as a symbol of compassion and humanism, but no holiness was above logic and nationalism for him. “When humanitarian interests are not served and in fact harmed by the cow and when humanism is shamed, self-defeating extreme cow protection should be rejected,” he wrote. “A substance is edible to the extent that it is beneficial to man. Attributing religious qualities to it gives it a godly status. Such a superstitious mindset destroys the nation’s intellect.”

Every now and then, an admirer of Savarkar raises the topic. “Can anyone imagine that the ‘Father of Hindutva’ advocated beef-eating (in special circumstances), rejected the divinity of the Vedas, denounced the sanctity of the caste system and launched a virulent attack on the hypocrisy of the priests?” wrote Ved Pratap Vaidik, a journalist close to several Hindutva figures. “Incidentally, Savarkar was a beef-eater,” wrote Varsha Bhonsle on Savarkar’s birth anniversary, February 26, in 1998. “For he was, above all else, a rationalist – a true Hindu – and eons ahead of contemporary Hindutvawadis.”

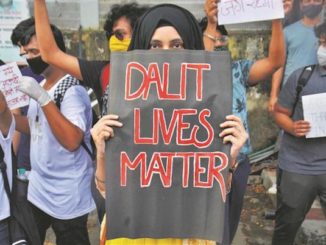

The cow’s holiness has long been a source of hurt and humiliation for Dalit communities.

“There is no untouchable community which has not something to do with the dead cow. Some eat her flesh, some remove the skin, some manufacture articles out of her skin and bones,” wrote BR Ambedkar, the architect of India’s Constitution, in his 1948 book The Untouchables: Who Were They And Why They Became Untouchables.

Dalit activists and scholars find the ban on cattle meat unethical and another example of caste hypocrisy. “Such laws are immoral,” said ‘Kuffir’ Naren Bedide, a thinker and social activist in Hyderabad, one of the editors behind Round Table India. He said this is about powerful castes imposing their sensibility on people who have consistently consumed beef, a source of cheap nutrition for poor people.

“Caste-Hindus say this is a matter of their religious sensitivity. What about Dalit traditions and sensitivities? Are they worth nothing?” he asked.

Why is an animal so sacred when human beings are considered so impure?

Who needs cow protection laws?

Not the farmers who are getting rid of cows and bullocks in favor of buffaloes and tractors. So will livestock breeders benefit from it? “Such laws will harm the poorest,” said Nitya Sambamurti Ghotge, a veterinary surgeon who heads Anthra, a group in Pune that has worked with rural livestock rearers since 1992.

Giving the example of the Rajasthan government amending its cow protection laws to register cattle breeders, and track their animals through microchips, Ghotge called cow protection laws “environmentally daft”, because this will put a great burden on shrinking pastures and fodder resources. “The rich will anyway get what they want, but how will the poor farmers and animal rearers get so much fodder?” she asked. Historically, farmers and animal rearers have been able to get rid of animals in difficult times for their survival, she said; now, that will become difficult.

Laws against cow slaughter will only criminalize the livestock trade, not protect the animals, said Ghotge. Only the smugglers and the law enforcement officials will benefit from the ban on cow slaughter, not the poor farmers or the livestock. Like the agriculture scientist

Ramanjaneyulu, Ghotge holds that the cow protection laws are unjust; it is about powerful urban people outsourcing the burden of cow protection on the rural poor, she said.

(Excerpted from the article “Why is the Cow a Political Animal?” by Sopan Joshi. Read Full article: https://in.news.yahoo.com/why-is-the-cow-a-political-animal-110119929.html)

Be the first to comment