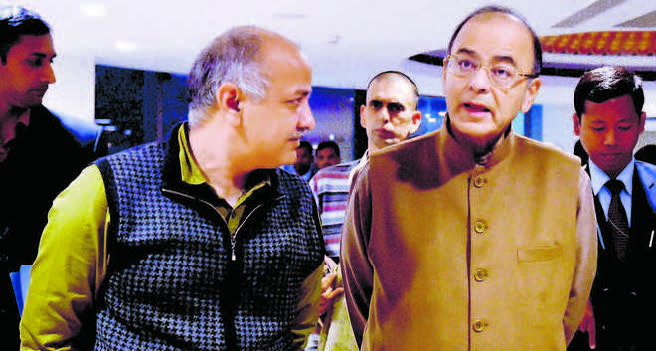

As expected, the latest Goods and Services Tax (GST) Council meet, headed by the Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley and with state finance ministers as members, could not arrive at any policy decision as far as the dual control of assessees is concerned. Consequently, the switchover to a single GST, subsuming almost all other commodity taxes will miss the stipulated date of its implementation, April 1, 2017.

The Union Finance Minister has now set September 16 as the new deadline. For the first time, a tax would be placed in the Concurrent list, which our Constitution makers meticulously avoided so as to ensure smooth Centre-state financial relations. One should go slow in view of the turmoil created by the demonetization drive. Jaitley’s contention that GST must be implemented before September 16 is not convincing. With the consent of states, the implementation could be postponed. The adoption of VAT took nearly 30 years, though it did not have any implications for our federal set-up. It simply replaced state sales tax by state VAT and central excise duty by Cenvat.

The chaos created by the demonetization drive has shaken the confidence of some states. After GST, they consider it the second blow to states’ autonomy, even though demonetization and the GST regime are aimed at ensuring transparent transactions. GST will neutralize the ill-effects of demonetization like fall in demand, market shrinkage and unemployment by extending market frontiers.

As GST ensures that tax credit is given to producers/ sellers for the taxes already paid, specialization and efficiency in production will be promoted. Producers and traders will get tax credit even on inter- state movement of goods and services. India will emerge as one common national market, with a seamless flow of goods and services across the country. There will be no tax on tax, so production and distribution of goods would become less costly, thereby boosting consumption and investment. Producers will be induced to invest in logistics and building warehouses and inventories, giving a fillip to ease of doing business. Implementing GST should not be viewed as a matter of prestige by the states or the Centre and both should adopt a pragmatic approach.

The most significant impact of GST will be on extending the volume of trade. A National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) study has evaluated the possible impact of GST on India’s international trade. It has been observed that, “The differential multiple tax regimes across sectors of production are leading to distortions in the allocation of resources as well as production inefficiencies. Complete offsets of taxes are not being provided to exports, thus affecting their competitiveness”. The study has estimated that “implementation of a comprehensive GST across goods and services will enhance the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by between 0.9 and 1.7 per cent”. Boosting trade, both internal and external, with forward and backward linkages may lift the GDP by 1-2 per cent. Of course, the organized sector may gain at the cost of the unorganized sector, yet the conversion of the informal sector into the formal is the prerequisite for reducing poverty and inequalities. Demonetization too has induced the informal sector to convert into the formal sector.

Earlier, the GST Council broadly approved the four-tier rate structure of five per cent, 12 per cent, 18 per cent and 28 per cent, but spared the essential items, including foodgrains, out of the purview of taxation. The Centre has been allowed to impose a cess on luxury items like high-end cars, tobacco, paan masala, aerated drinks and other demerit goods. This cess amounting to Rs 50,000 crore will continue for five years and the proceeds wherefrom will be used to compensate states for any loss of revenue on account of the switchover to the GST regime. The Centre has promised to abolish this cess after five years. Experience shows that once the cess is levied, it continues one pretext are another. However, the Centre must assure states that the proceeds from this cess will form part of the divisible pool if it continues thereafter. Now onwards, GST would be states’ main source of revenue. Direct taxes like income tax, corporation tax, capital gains tax, etc. are already within the Centre’s domain. Therefore, they must have considerable control over its administration. The only hitch now to implement GST is the exercise of power over the tax assessees. According to Jaitley, “One option is to divide assessees horizontally where those with a turnover of less than Rs. 1.5 crore a year will be assessed by the states and those with more than that will be shared by the states and the Centre”. The other option is to divide the assessees vertically into different strata and then divide different strata between the Centre and the states. The latter is cumbersome and would imply depriving states their right to tax businesses as majority of them are below Rs. 1.5 crore a year. This number has swelled in the aftermath of demonetization as consumers have shifted from small businessmen and traders to the organized markets that have swipe-machines for debit/credit cards. Falling demand and currency crunch collection from indirect taxes has shrunk, thereby adversely affecting state finances.

The Union Finance Minister hinted at a political solution. The GST law allows that in the event of a dispute, a two-third majority decision will prevail. This eventuality should not be explored right at the very start as it will not behove well for federal financial relations. In the past also the states have been losers whenever the decision was taken at the political level. For example, first, sales tax (which was a state subject) on some important items was replaced by additional excise duty in 1957. Then, tax on railway fare (whose 100 per cent proceeds went to states) was merged with railway fare. In 1959, the nomenclature of tax on a company’s income was changed to corporation tax and brought out of the divisible pool. All these decisions were taken at the party level. Another tax whose 100 per cent proceeds were meant for states, viz. estate duty was abolished in 1985. Even the present government at the Centre has abolished wealth tax in the budget 2015-16 and replaced it with 12 per cent cess on “super rich”, which is not sharable. Similarly, corporation tax has been scheduled to be brought down from the existing 30 per cent to 25 per cent and the states would suffer to the extent of 42 per cent, their share in tax revenue.

In the post-GST regime, local self-governments would be losers as they would have to forego revenue from local taxes like octroi, entertainment tax, entry tax, etc. That is why an institutional mechanism to safeguard their financial interests must be put in place

(The author is a former Professor of Economics & UGC Emeritus Fellow, Department of Economics, Punjabi University, Patiala)