NEW DELHI (TIP): The conventional narrative in India about the 1962 war has largely revolved around portraying the Chinese as the unbridled “aggressors”, who ripped apart the nascent “Hindi- Chini bhai-bhai” construct forever. The reality is slightly different.

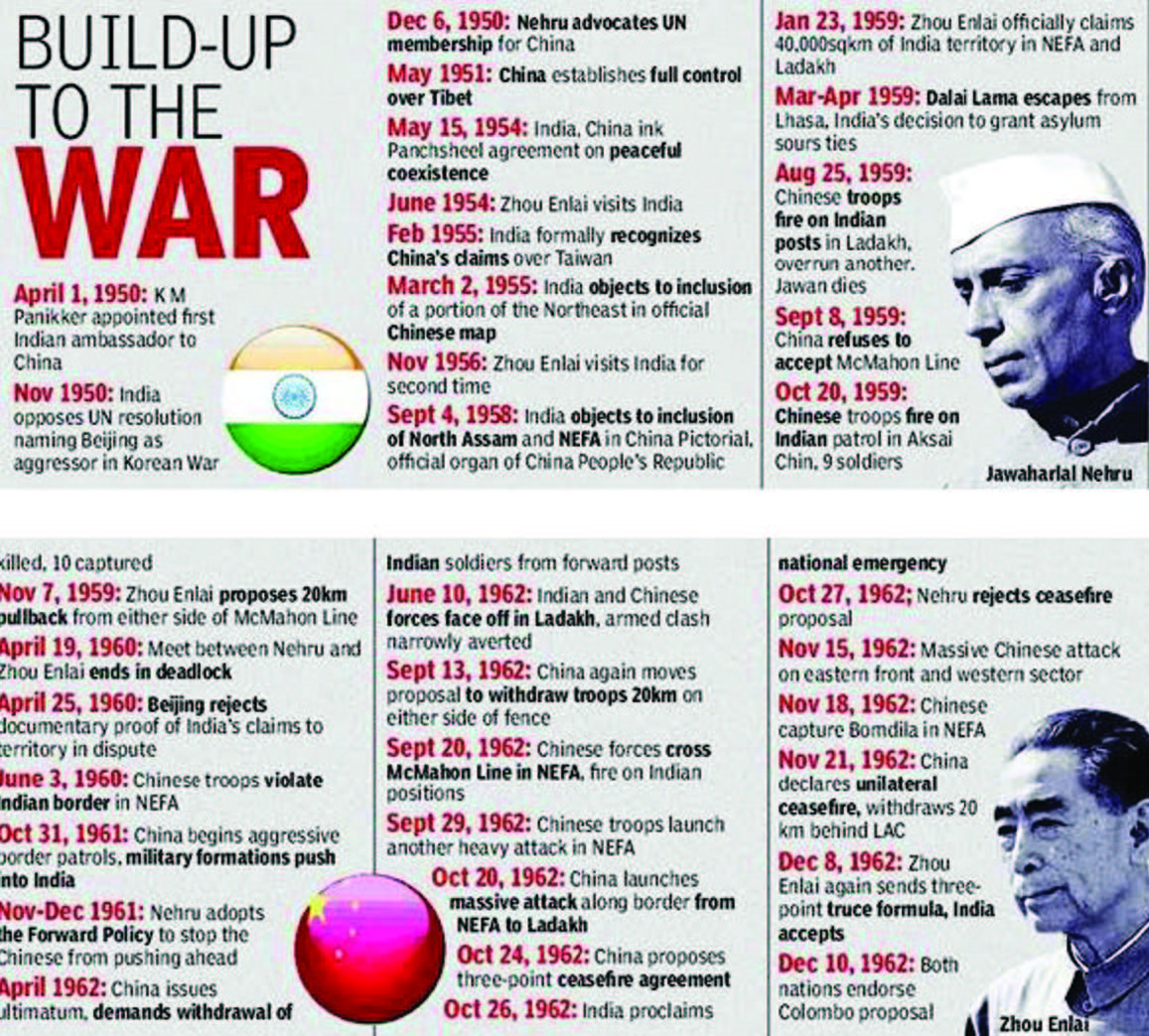

True, China was nibbling away at what India perceived to be its territory both in Ladakh and North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), as Arunachal Pradesh was then called, to consolidate its hold on Tibet. But what provoked Mao-led China to launch a full-blown military invasion into India on October 20, 1962 was the Nehru government’s ill-conceived and poorly executed Forward Policy, set in motion almost a year ago in November-December 1961.

Already smarting from the Dalai Lama’s escape to India in early 1959 and the bitter exchanges over the Mc-Mahon Line, which it considered to be a “legacy of British imperialism”, China decided to teach India “a lesson” it would never forget through the one-month war. The Henderson Brooks-P S Bhagat report on the 1962 military debacle, kept firmly under lock and key by the Indian government for the last 50 years, makes it clear the “unsound” Forward Policy — directing Indian troops to patrol, “show the flag” and establish posts “as far forward as possible” from the then existing positions —”precipitated matters”, sources say.

The sources, who have accessed the classified report, say the ill-timed Forward Policy “certainly increased the chances of conflict” at a time when India was militarily ill-prepared in Ladakh and NEFA, with China much better placed in terms of forces, equipment and logistics in both the sectors. The report apparently holds that the Forward Policy was based on the “flawed premise”, primarily driven by the then all-powerful Intelligence Bureau director B N Mullik, that “the Chinese would not react to our establishing new posts and that they were not likely to use force against any of our posts even if they are in a position to do so”.

This gravely erroneous assumption, given credence by a complicit Army headquarters despite being in direct contrast to an earlier military intelligence “appreciation” that the Chinese “would resist by force any attempts to take back territory held by them”, percolated down to all levels of command to usher in “a sense of false complacency”. What compounded matters was the “appalling” and “disastrous” military leadership and its decision-making, ignoring the advice of commanders on the spot. First, the Army headquarters paid no heed to the quantum of forces required to implement the Forward Policy. Both Ladakh and NEFA had “a minimum requirement” of an additional infantry division (over 12,000 troops) each, with necessary airlift and logistical backing, to somewhat re-address the imbalance with China, as had been reinforced by war games conducted earlier in 1960.

But no fresh induction of troops ever materialized. So, the report reportedly notes, while the Forward Policy may have been “politically desirable”, the Army simply did not have the wherewithal to implement it. The Western Command, for instance, had held that the Forward Policy should be kept “in abeyance” till there were enough Indian troops in Ladakh and that China should not be “provoked” into an armed clash. But the Army HQ disregarded all this. Neither did it strengthen Ladakh, nor reduce tensions with China. With the “probes forward” underway, the Army established 60 posts in sectors like Demchok, Chushul, Daulat Beg Oldi, Changla and Rezengla of Ladakh by July 1962, further stretching its already meagre resources there.

Many of these “very weak, far-flung and uncoordinated” posts had barely 10 soldiers each. Similar was the story in NEFA. Instead of strengthening the “defence line”, forces were frittered away in “pennypackets” in forward areas. Tawang, for instance, had just a depleted brigade, while China had two divisions in the sector. Similarly, Bomdila had only one battalion. Thus, as in Ladakh, in NEFA too, the Army was hardly in a position to adopt the Forward Policy. That it was adopted proved that the “higher direction of war” was “faulty”, based as it was more on preconceived notions that China would not react rather than sound military judgment, say sources. React the Chinese certainly did. Drafted by then commander of the Jalandhar-based 11 Corps Lt-Gen T B Henderson Brooks, who was assisted by Brigadier P S Bhagat, this “operational review” details at great length how the outnumbered and out-gunned Indian Army was first complacent, then collapsed and finally panicked and fled under the Chinese onslaught.

The report’s mandate was restricted to reviewing the Army operations but the covering note on it by Gen J N Chaudhari, who took over as Army chief after the war, did criticise then defence minister V K Krishna Menon’s continuous meddling in military matters. The report itself is sharply critical of the role played by Lt-General B M Kaul — a distant relative of Nehru and Menon’s favourite — first as chief of general staff at the Army headquarters and then as commander of the hastily raised IV Corps at Tezpur just before the Chinese invasion.

The report holds that the “lapses” by Lt-Gen Kaul and his “handpicked officers” were “inexcusable” and “heinous”, say sources, adding they should not have allowed themselves to be “pushed” into a military adventure without requisite forces and proper planning. The 4th Infantry Division in NEFA, for instance, was neither militarily prepared nor mentally adjusted to fight the Chinese. When the Chinese troops reached its gate, there was total confusion that ultimately ended in panic and flight. “Senior commanders” — like the 4th Infantry Division commander Major-General A S Pathania in NEFA — “let down the units” under their command, held the report.

Be the first to comment