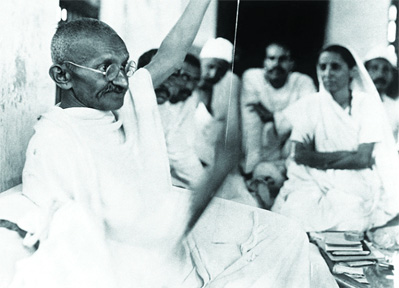

Mahatma Gandhi fondly referred to as Bapu, played an instrumental role in India‘s independence movement. He is referred to as the Father of the Nation. He was a great leader who followed the principles of Ahimsa (non-violence) and Satya (truth). His death anniversary falls on January 30.

Even after Independence, Mahatma Gandhi continued to work toward peace between Hindus and Muslims at a time of discord between the two communities. Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in Delhi on January 30, 1948, by Nathuram Godse.

Martyrs’ Day is observed on the death anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, who successfully led his country to freedom from the British Empire. Born in the small town of Gujarat, Gandhi studied to become a barrister and lived a pretty austere life, until he made his first trip to South Africa, and everything changed.

Life in South Africa exposed him to the deep class divisions of society and the evils of inequality. Gandhi’s life experiences shaped his worldviews. The discrimination he suffered in South Africa inspired him to fight for equality, the pain of losing his first child at the age of 16 made him a furious opponent of child marriage, and so on.

During India’s struggle for freedom, Gandhi advocated for peaceful demonstrations and inspired everyone to lead by example. He negotiated many peace treaties with the Britishers, before giving them the final ultimatum of departure. As the Indian constitution came into ratification, Gandhi took on the impossible task of building a country out of many provinces and territories.

Gandhi was vehemently opposed to the idea of partition of India. Even after the declaration of independence, he held regular demonstrations to establish his resistance. Gandhi’s objection to the partition was met harshly with Hindu nationalists, who accused him of appeasing the Muslims. On the eve of January 30, Nathuram Vinayak Godse, a notorious Hindu nationalist, shot Gandhi three times at point-blank.

Gandhi’s lifelong quest for non-violence ended with a bullet in his chest. On Martyrs’ Day, Indians from all around the world come together to celebrate the legacy of a great hero and acknowledge the futile destruction caused by violent extremism.

Monhandas Karamchand Gandhi was born in the small town of Porbandar, on the west coast of India, on October 2 1869. He belonged by birth to the Vaishya, or trading caste. His father died when he was 15 years old, and apart from that time, his mother became the greatest influence in his life. Her spiritual teacher was a Jain devotee. Among the Jains in India the central doctrine is the “sanctity of all life,” or Ahimsa, which is often translated as “non-violence.” This teaching remained paramount with Gandhi.

In South Africa

When 19, he came to London, qualified as a barrister (being “called” at the Inner Temple), and, returning to Bombay in 1892, set up a practice.

In 1896 he went to the Transvaal to help a client in a legal suit. That visit changed the whole course of his life. Seeing the social and political disabilities of his fellow-countrymen in South Africa, he decided to stay and help them and soon he had become their political leader and adviser. Meanwhile a religious conflict was taking place in within him. He read Tolstoy and corresponded with him: the result was an experiment in the simple communal life conducted by a small band of enthusiasts whom he had gathered together. He became an ascetic of the most rigorous type, setting great store by fasting and every form of self-denial. To the end of his life he remained a devout Hindu, but declared if ever “untouchability” were made part of Hinduism he would cease to be a Hindu. Perhaps the greatest religious effort of his life was to break down “untouchability.”

He went on steadily preparing his followers in South Africa for the struggle which was to end the indignities under which they suffered. Three times he went to prison. Little by little, the Indians gained the respect of the Europeans in South Africa by the faith with which they obeyed their leader in his campaigns of passive resistance. The summer of 1914 brought victory for the cause, and in July of that year the Gandhi-Smuts Settlement was signed.

When the war of 1914-18 broke out he came to Britain to organise an Indian ambulance corps (he had done ambulance work in both the Zulu campaign and the Boer War), but was taken so seriously ill the doctors sent him back to India. He founded a religious retreat on Tolstoyan lines near Ahmedabad, the Viceroy conferred on him the Kalsar-Hind Gold Medal for distinguished humanitarian work in South Africa, and, by general consent, he began to be called by the name Mahatma, which means literally “Great Soul.”

Non-Co-operation

A series of events quickly following each other at the end of the war brought him back into political leadership. The first was the passing of the Rowlatt Act, the second the tragedy of the Punjab and Amritsar, the third was what was regarded in India as the betrayal of the Indian Moslems by the Treaty of Sevres. He launched a non-co-operation movement in September,1920, but the non-violence which he demanded from his followers was broken. Congress revolted against his authority and the government selected the moment for eliminating him from the political scene. He was arrested, brought to trial for promoting disaffection, and sentenced to six years imprisonment.

On his return to politics he found himself a stranger in the existing atmosphere of disillusioned realism. He yielded the leadership to C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru, and retired to hand-spinning and the editing of his weekly paper. He showed no desire to resume his old position as dictator, and for that reason his moral supremacy was recognised even by his political rivals. So when at the time of the Simon Commission the old Congress leaders found that the young men were heading for revolution they decided that the only remedy was to call him back.The last phase

The last phase

His internment ended in April, 1945. He was then 76 and though his hold over the country was unshaken, he allowed the leadership in policies to pass increasingly into the hands of Mr. Patel and Nehru. After the election of the Labour Government, Great Britain made absolutely clear that it would lay down its power in India, and the principal question was whether it should transfer power to a unitary India or to two separate Governments of Hindu and Moslem India. Mr. Gandhi was known to believe that the division of India would be a calamity. At one time in the negotiations between Congress and the British he seemed to acquiesce in division, as the price of freedom, but later he reverted to unqualified opposition. Opinion in the Congress Working Committee was, however, for division as the only solution, and Mr. Gandhi therefore stood aside and left the decision to the younger men, believing that they were taking a disastrous course, but believing too that the leadership must now be in their hands.

His last few months he spent in continuous and not unsuccessful attempts to restore peace in one area after another as communal hostility flared up into massacre and calamity after the withdrawal of the British power. With a number of disciples he made a progress through the disturbed parts of Bengal, awing the excited masses into peace by the prestige of his name and his asceticism. His reply to a renewal of violence in Calcutta in September was a complete fast from everything but water. After three days peace was restored and his fast was broken. Again early this month he met communal disturbances in Delhi with another fast – of five days – which had great moral effect and led to solemn assurances of consideration for the Moslem minority. Less than a fortnight later he was to meet his death while engaged in religious observances.

Be the first to comment