The most flagrant abuse of the UAPA, and constant rejection of bail applications of those accused as a means of silencing opposing voices, can be seen in the Bhima Koregaon cases, including Fr. Swamy’s case, as well as the cases pertaining to protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), where mere thought is elevated to a crime. In multiple instances, evidence is untenable, sometimes even arguably planted, and generally weak overall. But as a consequence of UAPA being applied, the accused cannot even get bail. Courts cannot go into the merits of the case due to the Supreme Court judgment.

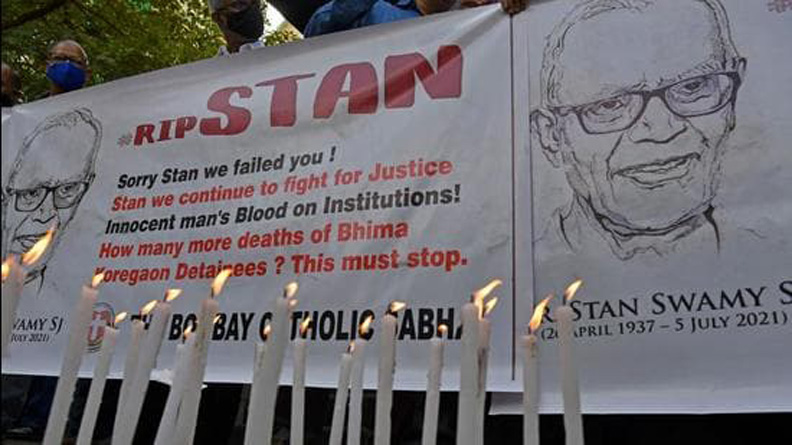

It has been 81 years since Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon was first published. The novel is set in the backdrop of the Great Purge of the late 1930s in the Soviet Union under Stalin. This period was marked by, among other things, political repression, police surveillance, general suspicion of the opposition, imprisonment, and executions. Decades on, thousands of miles away, darkness fell at noon in India too, when Father Stan Swamy passed away at a private hospital in Mumbai on July 5. Ominously reminiscent of the macabre world Koestler had drawn, Fr. Swamy’s death is much more than the death of an activist accused of terrorist activities. It is the result of a systemic abuse of majoritarian authority and disregard for the rule of law.

His life in a nutshell

For many, Fr. Swamy will be remembered as an inspiration. A Jesuit priest, he chose to make the upliftment of marginalized communities in Jharkhand his life’s work. He lived and worked in a single room, prolifically writing (over 70 books are credited to him) on dispossessed people. He was an activist for most of his life, and used the legal system to fight for the rights of those who were being unfairly targeted, and thought that the Constitution would help in securing justice, even moving the Jharkhand High Court in a public interest litigation on undertrials. When doing all of this, surely, he would never have imagined that his fate would be decided by the very system he used and believed in.

It started in August 2018, when the Pune police raided Fr. Swamy’s single-room home, seized his computer, cell phone, books and some classical music cassettes. Another raid took place in June 2019. Finally, on October 8, 2020, Fr. Swamy was arrested by the National Investigation Agency (NIA), under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the 16th to join a roster of professors, activists, writers, and public intellectuals, as a suspect in the Bhima-Koregaon case. Fr. Swamy, aged over 80, remained an accused, in the custody of the state, till his death. Besides being arrested for what many believe to be improbable causes, and being possibly the oldest person ever accused of terrorism in India, the most tragic story is how his detention was handled by the state, by the police and worst of all, by the courts.

Fr. Swamy was arrested on flimsy evidence of some propaganda material and communication with other activists in the field, such as Sudha Bharadwaj and Varavara Rao, who were also arrested for similar charges. The authenticity of some of the allegedly indicting documentation, including a key report, has been questioned by international forensic data experts. But the state defended its arrest arguing that these issues must be gone into only during trial, and that the accused — i.e., Fr. Swamy — should remain in jail until then.

Pointer to judicial decline

This is the outcome also of the problematic Watali judgment, which I discuss in subsequent paragraphs. Repeated pleas for medical assistance by Fr. Swamy were consistently ignored or dismissed. Medical reports taken on record clearly showed that Fr. Swamy had the degenerative Parkinson’s disease, and could not even do basic tasks, such as holding a spoon, writing, walking or bathing. Indeed, the court noted that he had a severe hearing problem, and was physically very weak. But even that did not move them. Every regular bail application that was filed by his lawyers was unequivocally rejected. When he applied for medical bail, the court kept adjourning the matter, and merely offered him the services of a private hospital. In my opinion, this demonstrates a lack of sensitivity on the part of the judges, which is deeply saddening.

The series of events that led to Fr. Swamy’s eventual and tragic passing is testimony to the judicial decline that we have seen in recent years, which coincidentally or not, appears to be coterminous with the current political regime in India.

Why is the political establishment, and the police, so emboldened to pursue cases under UAPA against individuals like Fr. Swamy? A key reason, undoubtedly, is the weak judiciary we have today. Indeed, our judiciary today suffers from a great many flaws besides mere weakness. In Fr. Swamy’s case, the judges displayed apathy of a shocking order. It is perplexing when, on the one hand, the Chief Justice of India grandiloquently states that personal liberties and fundamental rights must be protected, and courts do precisely the opposite.

A weakened central principle

It would not be too bold to suggest that the idea of the “presumption of innocence” — a central principle of criminal law and procedure — is on a terribly weak footing these days in our country, and this should worry all of us greatly.

The source of this worry is the Supreme Court of India itself. Its April 2019 decision in National Investigation Agency vs Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali on the interpretation of the UAPA has affected all downstream decisions involving the statute. This decision has created a new doctrine, which is that effectively, an accused must remain in custody throughout the period of the trial, even if it is eventually proven that the evidence against the person was inadmissible, and the accused is finally acquitted. The illogic of this veers on the absurd: Why must an accused remain in jail only to be eventually acquitted?

According to the decision, in considering bail applications under the UAPA, courts must presume every allegation made in the First Information Report to be correct. Further, bail can now be obtained only if the accused produces material to contradict the prosecution. In other words, the burden rests on the accused to disprove the allegations, which is virtually impossible in most cases. The decision has essentially excluded the admissibility of evidence at the stage of bail. By doing so, it has effectively excluded the Evidence Act itself, which arguably makes the decision unconstitutional. Bail hearings under the UAPA are now nothing more than mere farce. With such high barriers of proof, it is now impossible for an accused to obtain bail, and is in fact a convenient tool to put a person behind bars indefinitely. It is nothing short of a nightmare come true for arrestees.

This is being abused by the government, police and prosecution liberally: now, all dissenters are routinely implicated under (wild and improbable) charges of sedition or criminal conspiracy and under the UAPA. Due to the Supreme Court judgment, High Courts have their hands tied, and must perforce refuse bail, as disproving the case is virtually impossible. As a result of this decision, for instance, a High Court judge can no longer really adjudicate and assess the evidence in a case. All cases must now follow this straitjacketed formula of refusing bail. The effect is nearly identical to the draconian preventive detention laws that existed during the Emergency, where courts deprived people access to judicial remedy. If we want to prevent the disasters of that era, this decision must be urgently reversed or diluted, otherwise we run the risk of personal liberties being compromised very easily.

The most flagrant abuse of the UAPA, and constant rejection of bail applications of those accused as a means of silencing opposing voices, can be seen in the Bhima Koregaon cases, including Fr. Swamy’s case, as well as the cases pertaining to protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), where mere thought is elevated to a crime. In multiple instances, evidence is untenable, sometimes even arguably planted, and generally weak overall. But as a consequence of UAPA being applied, the accused cannot even get bail. Courts cannot go into the merits of the case due to the Supreme Court judgment.

An issue for the judiciary

When courts do go into such matters, as in the instance of the Delhi High Court granting bail to three young activists accused in a conspiracy relating to the 2020 riots in Delhi, the Supreme Court uncharacteristically decides to weigh in. The Supreme Court reportedly expressed “surprise” and dissatisfaction at the High Court’s decision, giving the direction that the decision will “not to be treated as precedent by any court” to give similar reliefs. Specifically, the Supreme Court reportedly said that “in a bail application, a 100-page judgment discussing all laws is surprising us”, perhaps forgetting that the case that started it all, i.e., the Watali judgment of the Supreme Court, was itself a judgment in a bail matter! This seems to imply that only the Supreme Court can hold forth on matters of statutory interpretation, and that High Courts — which are constitutional courts in their own right — may not? By extension, if statutes ought not to be examined at all by High Courts, does this mean that individual arrestees must languish in jail till, say, the constitutional validity of the statutes under which they are arrested are decided? Surely, this would be completely irrational.

Posterity will blame the judiciary for the incarceration and unfortunate death of Fr. Swamy, and the continued imprisonment of so many others like him. But voices will continue to rise in protest. As Fr. Swamy himself said, though, “we will still sing in the chorus. A caged bird can still sing.”

(The author is Former Chief Justice, Delhi High Court and Former Chairperson, Law Commission of India)