“Defenders of the market forget that a society that is indifferent to the needs of the deprived breeds its own contradictions. We witnessed an instance of this frustration last month when thousands of restless, thwarted and angry people set train compartments on fire. Their rage is understandable. This is perhaps the beginning of a crisis. The crisis of unemployment will relentlessly exacerbate political discontent.

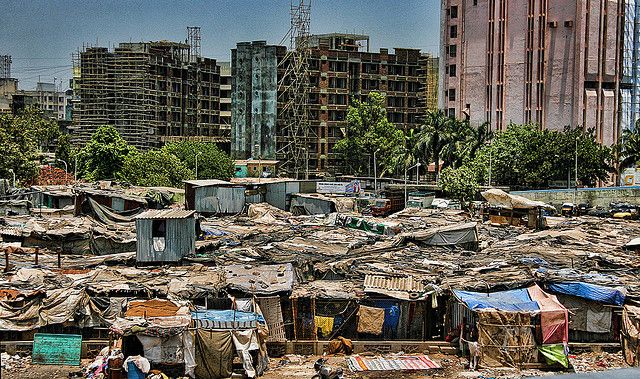

The divide: Policy-makers should take into account that a substantial chunk of the population lives beyond the pale of market forces.”

Poverty is not mere statistics. Statistics indicate that our people live in destitution. There is more, for poverty breeds multiple deprivations. The poor are not only denied access to basic needs, but they are also socially marginalized, politically insignificant in terms of ‘voice’ as distinct from the ‘vote’, dismissed and subjected to intense disrespect in and through the practices of everyday life.

According to the 2022 Oxfam Report, ‘Inequality Kills’, in 2021, 4.6 crore Indians fell into extreme poverty. In the same year, the wealth of billionaires increased from Rs 23.14 lakh crore to Rs 53.15 lakh crore. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy reports that 95 per cent of 3.05 crore Indians, of which 95 per cent are below the age of 29, are unemployed. As many as 1.8 crore of this number is graduates. If we care about our fellow citizens and about how they live, we should take serious note of these numbers. Poverty is not mere statistics. Statistics indicate that our people live in destitution. There is more, for poverty breeds multiple deprivations. The poor are not only denied access to basic needs, but they are also socially marginalized, politically insignificant in terms of ‘voice’ as distinct from the ‘vote’, dismissed and subjected to intense disrespect in and through the practices of everyday life.

There was a time when policymakers, charged by notions of redistributive justice, focused on progressive taxation, land redistribution, right to work, employment generation, quality of work, education and health of the working class. After the collapse of the socialist world in 1989, they casually abandoned grand visions of a decent society in which people encountered each other as equals, and not as members of two different worlds defined by garish wealth and mind-numbing poverty, respectively. We entered an era marked by the victory of political liberalism; a liberalism that had been pounded out of shape by the economics of neo-liberalism.

Across the world, the state withdrew from commitment to the well-being of its citizens and transited to what has been called the ‘entrepreneurial’ state. The belief that citizens have to create their own jobs, irrespective of the quality of work, is integral to neo-liberalism. The ideology simply does not recognize that the state throws needy individuals onto the not so tender mercies of the market. Generations of socialist thinkers have told us that the market has place only for those who can buy, and for those who can find buyers for the commodities they offer. It has neither compassion nor need for those who are born into poverty, and who spend their time looking for a handful of grain. We forget these lessons. And defenders of the market forget that a society that is indifferent to the needs of the deprived breeds its own contradictions. We witnessed an instance of this frustration last month when thousands of restless, thwarted and angry young people set train compartments on fire. Their rage is understandable; they cannot find a place in the lower rungs of government services, while other young people drive past in flashy cars, live lives of luxury and inhabit opulent neighborhoods.

This is, perhaps, the beginning of a crisis. The crisis of unemployment will relentlessly exacerbate political discontent. The former cannot be resolved by sops to reduce poverty. The latter can hardly be resolved by promises of cash transfers during elections. In the debate on equality, the philosophical school of sufficientarianism suggests that people should be given enough to eat; how does it matter if they are unequal? Egalitarians insist that the challenge is not only about giving people enough to eat; it is about the right of everyone to participate in social, economic and political transactions as equals. The objective of equality is to enable people to be authors of their own lives. People can hardly write their own history if they are told condescendingly during elections: ‘Give me your vote and I will give you a thousand or so rupees.’ Is this all India’s power elites owe the poor? Not structural change?

It is time we take a once valued concept out of the closet, dust it, refashion it to suit our times, and present a picture of the world we should be living in, instead of the world we do live in. The concept is that of social democracy. Social democracy is, as all concepts in political theory are, contested. The most persuasive case for social democracy is offered by Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski (1927-2009). The concept, he said, offers no ultimate solution for humankind. It merely speaks of ‘an obstinate will to erode by inches the conditions which produce avoidable suffering, oppression, hunger, wars, racial and national hatred, insatiable greed and vindictive envy.’ These ills of the human condition have to be fought through forms of collective action. Collective action has to concentrate on the antidote to poverty and inequality: social democracy which promotes well-being. Leaders cast, but an occasional eye on the suffering, and charitably extend a thousand rupees here and a thousand there as a personal favor. In a democracy, citizens do not need charity, they have rights to freedom and equality. They do not need the largesse of a medieval monarch, nor do they need to thank him repeatedly. Social democracy lacks the fire and thunder of regressive right-wing politics. It lacks the romantic imagination of a post-revolutionary, perfectly egalitarian world. But it does tell us that a world where little children do not have to beg for cast-off food in bare feet and tattered clothes, is far, far better than the one in which people’s life chances are shaped by inequality. An individual who is unequal to others in society can hardly write her own history. Inequality fosters unfreedom. In history, revolutions have been inspired by freedom, but also equality.

(The author is a Political Scientist)

Be the first to comment