“Since the BJP came to power in July 2019 (after the fragile Janata Dal Secular-Congress coalition sunk), the topmost question is, how much of Hindutva will actually shape the results of this poll? Truth be said, in the case of Karnataka, Hindutva has made more noise than actually polarize voters. The noise always emanates from the coastal districts of the state. However, the genie and genius from that laboratory have not spread so much to the plains or the mountains in the state. At best, they have offered an air cover in these regions but have not mingled too much in the soil. This has been true with the previous elections and is likely to be the case this time, too.”

What will the numbers be? That is the question thrown at you in an election season, and that is precisely what is being asked about the Karnataka Assembly polls slated to take place on May 10. The numbers will be clear on May 13. Anything said before that can either be a reasoned conjecture, an intelligent guess or an astrological prediction. But before the numbers come, there are narratives that will somewhat decide the numbers. Therefore, it may serve us well to look at the narratives that are shaping the Karnataka elections.

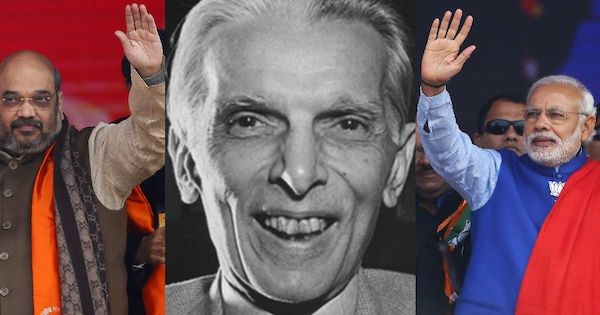

Hindutva has made more noise than actually polarize voters. This has been true with the previous elections and is likely to be the case this election, too.

Since the BJP came to power in July 2019 (after the fragile Janata Dal Secular-Congress coalition sunk), the topmost question is, how much of Hindutva will actually shape the results of this poll? Truth be said, in the case of Karnataka, Hindutva has made more noise than actually polarize voters. The noise always emanates from the coastal districts of the state. However, the genie and genius from that laboratory have not spread so much to the plains or the mountains in the state. At best, they have offered an air cover in these regions but have not mingled too much in the soil. This has been true with the previous elections and is likely to be the case this time, too.

A big reason for this seeming equilibrium is BS Yediyurappa, who has been largely responsible for the BJP’s success in the state. He has been more a Mandal politician than a Hindutva champion. This is probably because he picked up his political game in the midst of socialists and Lohiaites in Shimoga and Mysore districts. He came of age, electorally speaking, when the undivided Janata Dal was the real alternative to the smug Congress.

Even a fortnight ago, in an interview to a Delhi newspaper, Yediyurappa said: ‘Hijab, halal issues are not necessary. I will not support such things. Hindus and Muslims should live like brothers and sisters. From the beginning, I have taken this stand.’ Yediyurappa has been instinctually attuned to caste identity issues. He has skillfully and cunningly arranged the mix-and-match of castes to generate votes for the BJP over the decades.

But the BJP got rid of him in the middle of 2021. His age, other vulnerabilities and his family’s alleged corruption aside, the BJP wanted to change the narrative for the state. The caste game was getting too balkanized, and it, after all, did not yield a clear majority to the party in both 2008 and 2018. The majority to form a government, both times, was arranged later through defections that assumed a wry botanical imagery — Operation Lotus. Post-Yediyurappa, the BJP was in search of a more universal (read Hindu) electorate in the state instead of the one aggressively fenced by caste.

Basavaraj Bommai became Yediyurappa’s replacement. The BJP’s game plan, it appeared, was to get someone from a dominant Lingayat community (which has remained loyal to the BJP ever since Ramakrishna Hegde and JH Patel moved them to the ideological Right in 1999) to introduce aggressive Hindutva. That is when issues related to halal, hijab, Tipu Sultan’s barbarity, love jihad, Hanuman janmabhoomi, carbonization of history textbooks, etc., started making headlines every day in the state. The BJP wanted the coastal waves to inundate the rest of the land. But nine months before the polls, the BJP seemed to realize that none of this was getting enough traction. The big shifts were not happening. The status quo of vote shares that Karnataka had seen since the 1980s was not getting upset or upturned. On the other hand, Hindutva was impacting the revenue pocket of the state — the Bengaluru capital region, which contributes over 60 per cent of the state’s revenue. Development branding, something the BJP has always tried to juxtapose with its communal agenda, was getting dented. It tactfully withdrew and went back to the familiar game of caste identity politics.

That is when Yediyurappa was brought back to the center stage, not to lead the campaign from the front but as a patriarchal figure to manage caste complications. The Bommai government even urgently rejigged the caste quotas to cultivate a certain numerically dominant sub-sect among Lingayats, Dalits and the backward classes. The only communal signal it sent out there was to strip the Muslims of their 4 per cent backward class quota that HD Deve Gowda as chief minister had given them in 1995. This return to caste was a default safety measure for the BJP. When it comes to the Congress, its narrative is rather uncomplicated. It believes that the palpable anti-incumbency against the BJP will automatically put it in the driver’s seat. It has been advertising the BJP’s scams. It is also trying to snatch unhappy elements among Lingayats (Jagadish Shettar and Laxman Savadi) from the BJP and present a narrative that the Lingayats are moving out of the BJP. It has no clear outreach for minorities (read Muslims) or the more oppressed Dalits (Madigas who have voted for BJP) or the tribes (especially Valmikis). Its backward class messaging is largely confined to Kurubas and Idigas — two of the 100-odd communities on the list.

When it comes to Janata Dal Secular and the Vokkaligas who dominate southern Karnataka, HD Deve Gowda, the patriarch of the Cauvery basin, is guarding his terrain by campaigning at the age of 89. He may retain his 20 per cent vote share. His party has gone to the people with a well-structured development programme. He also sorted out family complications in time. His son HD Kumaraswamy has gone round the state more than any other leader this season. If saffron voters want to teach a lesson to the BJP, but their conscience wouldn’t permit them to go with the Congress, the surprise beneficiary may be Kumaraswamy.

( Sugata Srinivasaraju is a senior journalist and author)

Be the first to comment