We have lived for far too long in the 21st century with the carcasses of ideologies of the 19th century. They were already outdated by the second half of the 20th century; they make no sense in the 21st. These ideologies received from the past force square pegs of a new reality into prefabricated round holes. They fail to incorporate new ideas, issues and energies.

“It’s the eighth year of a charismatic Prime Minister. The economy is in a shambles, with low growth, high unemployment and rising inflation. Doubts are giving way to disillusionment, disappointment to anger. The imperious political dispensation treats popular protests with disdain.”

It’s the eighth year of a charismatic Prime Minister. The economy is in a shambles, with low growth, high unemployment and rising inflation. Doubts are giving way to disillusionment, disappointment to anger. The imperious political dispensation treats popular protests with disdain.

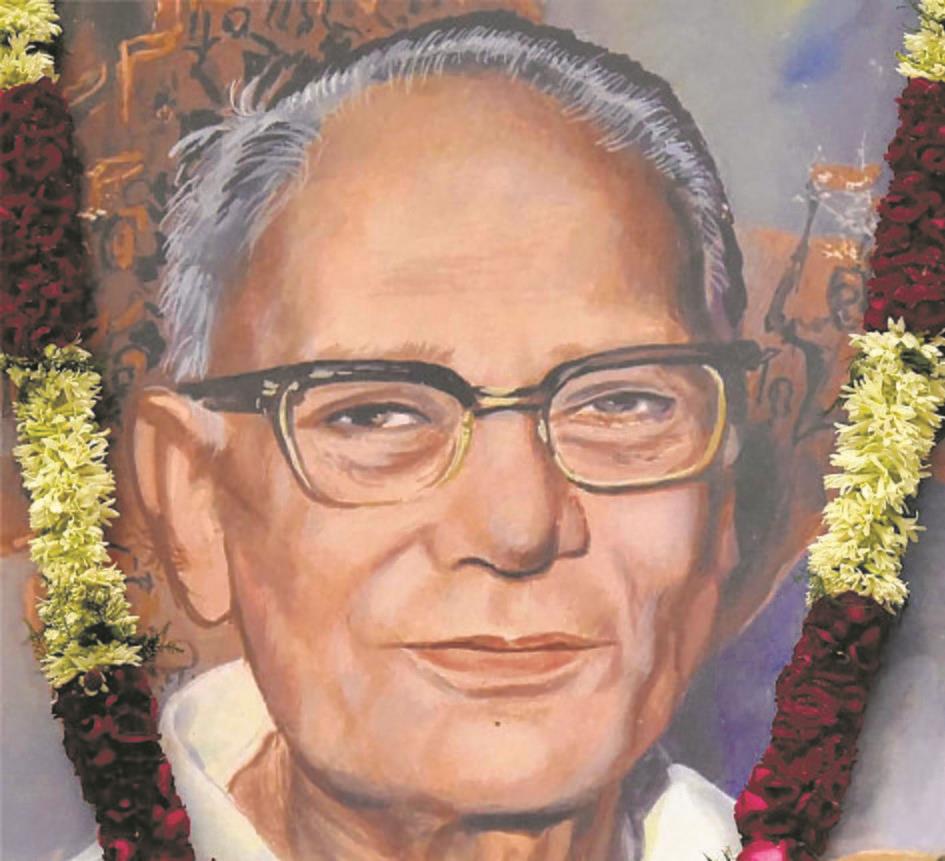

No, I am not depicting Narendra Modi’s India. This fragment, nearly half a century old, is from Indira Gandhi’s India. The date June 5, 1974 was a turning point in the history of the Bihar movement. Jayaprakash Narayan or JP gave a call for ‘Sampoorna Kranti’ or total revolution at a massive rally in Patna that day. Sampoorna Kranti became the rallying cry of the Bihar movement. Slogans like “Sampoorna kranti ab naara hai, bhavi itihaas hamara hai” reverberated during that famous challenge to Indira that led to the Emergency and, finally, the ballot revolution of 1977. Does that lapsed ideological lingo of a bygone era hold some relevance for us today? I think it does. That is why the Samyukt Kisan Morcha’s decision to observe June 5 this year as Sampoorna Kranti Diwas holds a deep historic significance.

In my previous birth as a student of public opinion, attitude and behavior, one thing never ceased to surprise me: the optimism of the Indian public. No matter how horrid the reality on the ground, a question about expectations of the future always got an overwhelming positive response. The analyst in me found this intriguing. The political animal in me found this frustrating.

Looking back, I think this naïve optimism may have been the oxygen that kept democracy alive despite all odds.

That optimism is under threat today. Take three recent examples. Mahesh Vyas of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy reports that the share of households that expected a rise in their income over the next one year had come down to just five per cent in April this year, compared to 30 per cent in 2019, when the economy was already in a bad shape. On the same day, FICCI’s Business Confidence Survey — no good indicator of popular mood — reported a nosedive in its index of business confidence. More to the point, Yashwant Deshmukh — no critic of Modi government — writes that the CVoter poll found 80 per cent Indians in a state of despondency, saying they do not think anything is on the right path. Hope is the most scarce commodity in today’s India. Loss of hope is an indicator of the loss of faith in the Modi government. But this is also a challenge to the Opposition and democratic system. India desperately needs hope.

This is not a challenge of crafting a positive political communication. This is not about coining a smart political slogan, or a new ‘jumla’. Indians have been through that. They believed in “achhe din” and have seen the reality. They still yearn for hope, but one that is believable, that maps on to the ground, that shows a path and offers a vehicle.

This is what ideologies do. An ideology provides a frame to understand the present, diagnose what is wrong with it and identify seeds of change. It offers a utopia, an imaginary future destination that we must strive for. And it traces a path from the present to that imagined future with the help of agents of change and their strategies.

It is not fashionable to use this word in the 21st century, after the collapse of political systems that foregrounded their ideologies. But let us not delude ourselves: those who call themselves non-ideological are also purveyors of an ideology, the ideology of status quo. We don’t need that. India needs a forward-looking ideology that provides a frame for instituting hope.

This cannot be done by any of the existing ideologies. We have lived for far too long in the 21st century with the carcasses of ideologies of the 19th century. They were already outdated by the second half of the 20th century; they make no sense in the 21st. This applies as much to the ideologies of the Right as it does to the Left. These ideologies received from the past force square pegs of a new reality into prefabricated round holes. They fail to incorporate new ideas, new issues, new energies.

Instead of integrating various ideas, we turn to patchwork ideologies like Gandhian Socialism or hyphenation like Ambedkarite-Feminism or absurd labels like Left-Liberal. No wonder these ideologies or their combination do not generate the kind of hope that India needs today.

This is where JP’s call for a total revolution comes in. By the time he gave this call in 1974, he had been through the entire spectrum of ideologies of his time. Beginning as a naïve nationalist in his childhood, he converted to Marxism-Leninism in his youth and was an ardent champion of the USSR. Disillusionment with communism in his 40s led him first towards democratic socialism and then towards Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave. Through the 60s, he advocated a communitarian ideology. His call for a total revolution was not one more stage in his intellectual journey; it was the summation of the entire journey and an attempt to integrate all the ideologies of the 20th century for our purpose.

JP was ahead of his times. Thus, the idea remained necessarily sketchy. He did not go beyond saying that total revolution entails a radical refiguring both of the system as well as the human being, that it meant a revolution in the political, economic, social, cultural as well as spiritual spheres. He insisted that a revolutionary transformation must be non-violent and cannot happen overnight.

Standing on his shoulders, we can do much better. We can incorporate ideologies that JP’s wide spectrum did not encompass: Phule-Ambedkarite legacy, feminism, environmentalism. We can attend to issues that he did not quite grasp: caste, gender, ecology, information order.

We can discard many of the superstitions of the ideologies of the 19th century: the idea of a vanguard of history, and universal models of revolutionary transformation and one-stroke revolution.

Instead of deducing the picture of a good society from a universal utopia, we can anchor a new ideology in the values of the Indian Constitution. We can revolutionize the idea of revolution.

Creating such an ideology is one of the biggest challenges of our times. This is not just a challenge for political leaders and workers; this is a challenge for all social activists, intellectuals, academics and artists. Let this June 5 be the starting point of this difficult but necessary journey.

(The author is National President, Swaraj India)