Besides technological and scientific goals, lunar missions have great geopolitical significance

“Besides the technological and scientific goals, the moon missions have great geopolitical significance. The space race was mostly driven by political ambitions and the Cold War. After the USA won the first round by accomplishing a manned mission on the moon, the Soviets took to robotic missions for lunar exploration and pioneered rover and ‘sample return’ missions. Decades later, China joined the race and has executed lander and sample return missions; it plans to send a manned mission to the moon by 2030. Its Yutu-2 rover, which landed in January 2019, is still alive on the lunar surface. Russia revived its interest in lunar missions, as demonstrated by its latest lander-rover lunar mission which failed days ahead of India’s succeeded. An aggressive space programme being pursued by China, steady progress being made by India and new collaboration emerging between China and Russia have added new dimensions to the contemporary space race.”

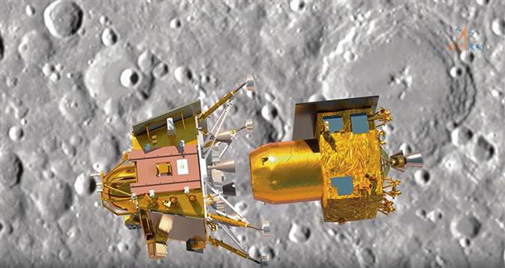

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has executed one of its most complex missions till now. Chandrayaan-3 successfully landed on the surface of the moon on Wednesday. The lander, with the rover in its belly, descended on the moon as planned, and is expected to explore the lunar surface over the next 14 days. This is not only a scientific and technological landmark but also marks India’s entry into an exclusive club of spacefaring nations which have accomplished a soft landing on the moon. Since the beginning of the space age over half a century ago, only three countries have been able to achieve a soft landing on the moon — the USA, Soviet Union/Russia and China. This is not only a scientific and technological landmark but also marks India’s entry into an exclusive club of spacefaring nations.

Chandrayaan-3 is India’s fourth deep-space mission (three lunar missions and one to Mars) and the second one designed to soft-land on the lunar surface. Indian space scientists began thinking of deep-space missions around 2000 as a logical next step after having launched several communication, remote sensing and earth observation satellites. The three lunar missions have had clear scientific and technological objectives. The overall objective is to develop and demonstrate end-to-end technological capability to design, fabricate, launch and operate deep-space missions. Chandrayaan-1, launched in October 2008, consisted of an orbiter and the Moon Impact Probe (MIP) that was designed to crash into the lunar surface (as opposed to landing softly). The orbiter was successfully placed around the moon to collect chemical, mineralogical and photo-geological data from the lunar surface using onboard scientific instruments. The MIP was crash-landed into the lunar surface near the Shackleton Crater on the lunar south pole.

Chandrayaan-2, launched in August 2019, was an advancement over the first mission as it included a lander and a rover in addition to the orbiter. The lander and the rover were to be placed on the lunar surface through soft landing, unlike the MIP of Chandrayaan-1. While the orbiter was successfully placed in the lunar orbit and ejected the lander module, its soft landing on the lunar surface could not be achieved. The present mission, Chandrayaan-3, did not have an orbiter component. Its primary objective was to deploy the lander and the rover to carry out scientific experiments. Future missions will have to be designed to not only land on the lunar surface but also bring soil and rock samples back to Earth.

The missions so far have yielded important scientific results. During its freefall, the MIP released by Chandrayaan-1 collected valuable data and the plume it produced after it hit the lunar surface suggested the existence of water in the lunar atmosphere. Subsequent analysis of data collected by instruments in the orbiter, such as the Moon Mineralogical Mapper, confirmed the presence of water-bearing molecules. The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter carried a camera of very high resolution (0.3 meters), providing data which proved to be of great value to the global scientific community. The orbiter has lasted much longer than its planned life of one year. The scientific payloads on the lander and the rover in the present mission are expected to yield new data about the chemical and elemental composition of lunar soil and rocks.

The journeys to the moon have been rocky for ISRO. Chandrayaan-1 did not last its designed mission life of two years. It faced technical issues from November 2008 onwards due to the abnormally high heating of some of its instruments. After a few months, its orbit was raised from 100 km to 200 km to keep the onboard temperature at tolerable levels. Then, it suffered a sensor failure, which ultimately made the satellite inoperable. ISRO lost communication with Chandrayaan-1 on August 29, 2009. Chandrayaan-2 was a partial success as the orbiter was successfully transported and placed in the lunar orbit, but the lander failed to touch down as planned. Chandrayaan-3 was designed to achieve that task. Instead of an orbiter, it had a propulsion module to carry the lander and rover from the injection orbit till the 100-km lunar orbit.

Besides the technological and scientific goals, the moon missions have great geopolitical significance. The space race was mostly driven by political ambitions and the Cold War. After the USA won the first round by accomplishing a manned mission on the moon, the Soviets took to robotic missions for lunar exploration and pioneered rover and ‘sample return’ missions. Decades later, China joined the race and has executed lander and sample return missions; it plans to send a manned mission to the moon by 2030. Its Yutu-2 rover, which landed in January 2019, is still alive on the lunar surface. Russia revived its interest in lunar missions, as demonstrated by its latest lander-rover lunar mission which failed days ahead of India’s succeeded. An aggressive space programme being pursued by China, steady progress being made by India and new collaboration emerging between China and Russia have added new dimensions to the contemporary space race.

Chandrayaan-1 was a turning point for ISRO not only because it was its first deep-space mission but also because it attracted much wider public attention. The mission fired the public imagination in many ways. For instance, ISRO was flooded with applications from aspiring scientists and engineers wanting to work for it. All this made the agency realize the importance of public engagement. Then followed the Mars Orbiter Mission, which also garnered attention. In the run-up to Chandrayaan-3, the space agency aggressively leveraged social media platforms to reach out to the public with updates and images of the lunar surface taken by the lander module. For the first time, ISRO invited educational institutions to “actively publicize” the mission and organize live-streaming of the Chandrayaan-3 soft landing in schools and colleges. While ISRO reaching out to educational institutions is welcome, such engagement should go beyond publicity. Missions like Chandrayaan should be used to promote greater understanding of science and scientific temper. This is much needed at a time when pseudoscience is on the rise and scientific ideas are under attack.

(The author is a Science Commentator)