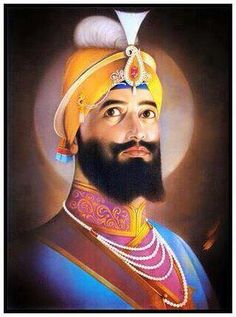

Memories are important for our personal and collective identity. We celebrate Baisakhi by remembering the phenomenal personality, life, and legacy of Guru Gobind Singh:

“Whether he was at Anandpur riding his handsome blue charger, his regal plume setting off his wiry and commanding figure, with a knightly body of devoted and daring Sikhs following him, or in the jungle of Machhiwara, barefoot and forlorn, his heart was constantly in harmony with the Divine, neither losing its qualities of love and compassion in one situation, nor giving way to despair in the other…. It is difficult to imagine a genius more comprehensive and versatile.”

–Professor Harbans Singh, Guru Gobind Singh (1966)

We canpicture the Guru with his resplendent plume astride his royal-blue stallion, hear his valiant melodies, feel his intense spirituality, absorb his egalitarian ideals, value his arduous battles, and recognize his vast metaphysical worldview. The consequence? We are energized to put his message into practice.

Historians often make a rupture between the “peace-loving” Guru Nanak and the “crusader-warrior” Guru Gobind Singh, which is not only erroneous, but also detrimental to Sikh psyche and society. These either-or binaries take away the multi-dimensionality of the Gurus and give a skewed sense of their ideology and praxis. The Tenth Guru as a natural successor to the First who challenged social hegemonies, criticized degrading and exclusive cultural norms, and validated heroism. Guru Nanak’s poignant protest against Babur’s invasion of India and his devastation of innocent people—both Hindu and Muslim, male and female— resonates throughout Guru Gobind Singh’s fight for freedom and justice. In his own voice we hear the Tenth’s awareness of his divine purpose: identifying himself with the founder Nanak, he commits to reverse the moral imbalance of his contemporary society, one in which the saints were being persecuted and the tyrants rewarded.

The Guru spent his childhood in Patna where his parents Guru Tegh Bahadur (Nanak 9) and Mata Gujari were spending some time. Several stories of little Gobind are present in the Sri Gur Pratap Suraj Granth. As we all know stories may not be factual, but they exude enormous power as articulated by Muriel Rukeyser, “the universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” The childhood stories portray an enthusiastic, empathetic, wise, loving, and a happy Gobind. Professor Harbans Singh effectively conveys the youngster’s impact: “Its [Patna’s] air was intoxicated with the presence of so lovable a being. Its streets echoed with the prattle and mirth of Gobind Singh as he grew up and started ransacking the place with a group of playmates.” He would frequently overstay his playtime and return home late which would delay the evening liturgy. Interestingly, even today the tradition is maintained, for the evening Rahiras in the Patna Sahib Gurdwara is still read after the usual canonical hour. In one of the stories, little Gobind announced that he had found a second mother. When Mata Gujari asked how will one son play on two laps, the son responds most poetically: “Just as one moon plays simultaneously in two pools.” With his narrative flair, Professor Harbans Sing hdelineates a vivid portrait of the Guru which fosters not only a close relationship with the historical figure but also a deeper understanding of his adult psyche and subsequent accomplishments.

Unfortunately, as the family is resettling in Anandpur in the Shivalik hills, the nine-year-old comes face to face with the tragic martyrdom of his father. The son lost his father; the Sikhs, their spiritual leader. And the torture and the cruelty with which Guru Tegh Bahadur met his end in Delhi in 1675 was so agonizing. But the qualities embodied in the young Gobind we met earlier mature forcefully. He “remoulds the spirit in Anandpur” by converting the pain and distress of his father’s death into a bracing memory. His personal loss, pain, and anger are sublimated into a dynamic and creative mode of living. The hills around Anandpur begin to echo with the chanting of sacred verses and heroic ballads, and with the gallop of the young Guru’s horses. The elemental sounds pierced their depressed emotions and the anguished Sikh hearts began to beat with a new consciousness. His father’s death did not make him vindictive, a claim made by some scholars. Professor Harbans Singh describes the diverse ways in which Guru Gobind Singh diverted the minds of his Sikhs from thoughts of retaliation, and inspired a healthy and harmonious attitude. “His heart was constantly in harmony with the Divine, neither losing its qualities of love and compassion in one situation, nor giving way to despair in the other.” In fact, what his father was for him, the young Guru becomes for his community.

The poetic genius of the Guru and his aesthetic sensibility must be remembered. With our single-minded attention on the Guru’s battles and daring deeds, we overlook his artistic brilliance. He was “a poet of deep spiritual insight” along with his various significant roles — that of a “prophet,” “kingly patron of learning,” “natural leader,” “soldier of unmatched military prowess and courage,” “social reformer,” “liberator,” “saint with a wide human sympathy,” and more. Actually, all his talents perfectly fuse in his poetic enterprise.

And so sacred poetry vitally important from the very origins of the Sikh faith acquires an even more urgent impulse from the Tenth. The first Guru identified himself as a sairu/shair, from the Arabic word for poetry al-shi’r, which the Islamic scholar S.H. Nasr traces to consciousness and knowledge. Clearly the Asian understanding of poetry is very different from “making” or “crafting” that underlies the Greek poesis. In the Sikh instance, the Gurus are so consumed by their awareness and love for the Divine that their words flow out instinctively. The first Sikh community in Kartarpur evolved around the founder Guru’s sonorous rhyme (bani). Sikh subjectivity is born from the Guru’s bani; Sikh subjectivity is nourished by Guru’s bani. For Guru Gobind Singh poetry was the means of revealing the divine principle, and concretizing the vision that had been vouchsafed to him. His popularly recited Jaap carries forward the first Guru’s Japu in breathtaking speed. It is a marvelous profusion of divine attributes that flashed on the tenth Guru’s artistic horizon. He ends at verse 199 rather than at a round figure to signify that there is no culminating point. The cascading terms saluting the infinite One are dynamic, their rhythm is speedy, a perfect proof of his spiritual lineage from Nanak 1.

Through his verse the tenth Guru expressed the themes of love and equality, and a strictly ethical and moral code of conduct. Deprecating idolatry and superstitious beliefs and practices, Guru Gobind Singh evoked love for the singular Divine. His quatrains (savvaye), for instance, underscore devotion as the basis of religion. They reject all forms of external worship and cast Guru Nanak’s message of internal love in undulating rhythm — “jin prem kio tin hi prabhpaio” (those who love find the Transcendent). Rather than an impassive list of do-s and don’ts, these poetic rhythms hit us at a visceral level and reproduce spontaneous re-actions.

Metaphysical poetry is also essential to his historic inauguration of the Khalsa. How did Guru Gobind Singh prepare the invigorating amrit drink that his five beloved sipped and spewed out all hegemonies of caste and class? The Guru churned water in a bowl with his double-edged sword — in the accompaniment of bani. The alchemy of iron intensified by the vigor of the Gurus’ hymns and sweetened by the sugar-puffs put in by Mata Jitoji was the revolutionary drink that the Khalsa consumed to fight against all forms of tyranny and oppression. By sipping amrit prepared in and with the sight and sound and touch of Guru Nanak’s Jap, Guru Gobind Singh’s Jaap, Swaiyyas, Chaupai, and Guru Amar Das’Anand, the Khalsa is born, and is thereafter daily nurtured. The nutrients physically taken inside the body become a part of the blood stream of the newly born members, and continue to feed them throughout their lives and that of their future generations. The five items of faith (bana) given by the Guru to his beloved five are made out of bani. The fusion of the devotional and the martial was the most important feature of the philosophy of Guru Gobind Singh and of his career as a spiritual leader and harbinger of a revolutionary impulse.

On that historic Baisakhi of 1699 Guru Gobind Singh meaningfully retrieved his past, and set it in motion for the future. The Sikh religion is not static but a rich, ever-accumulating tradition. It is for us to keep the Guru’s dynamic momentum going. Celebrating Baisakhi at the Indian Consulate in New York City 2021 inspires us to be courageous, creative, empathetic, innovative, and loving. In our dangerously divided world, the Guru serves as a wonderful role model. We must follow his appeal

manas kijatsabaiekaipahichanbo….

ek hi sarupsabaiekai jot janbo (Akal Ustat: 85)

Recognize: humanity is the only caste….

Know: we are all of the same body, the same light.

There is an urgency in the Guru’s tone as he voices the two imperatives “pahichanbo” (recognize) and “janbo” (know). He does not want us to be afraid of one another; he does not intend for people to merely tolerate one another with different colored eyes or complexions or accents or texture of hair. Such differences happen to be an effect of our different geographical regions and cultural locales: “Different vestures from different countries may make us different; nevertheless, we have the same eyes, the same ears, the same body, the same voice — niareniaredesankebhes ko prabhaohaiekainainekaikanekaidehekai ban” (Akal Ustat: 86). Our very birth and biology justify our human equality. The Sikh Guru makes it our responsibility to know (janbo) that we all have the same body (ek hi sarupsabai), and are formed of the same spiritual light (ekaijoti). We are urged to open ourselves, generate new potentialities, forge close relationships — build ourselves a rich and meaningful human community.

Let us rejoice and sing together the felicitations from Bhai Vir Singh’s Gurpurab Gulzar:

Ajjkhushian mane khalsa

Mainundarastere di lalsa

Kar darshan nalnihal

Ajj aa mil kalgivaliah

Auhkalgianvala aa gia

Mainuncarnanvicsamalia

Hun vicchurnamelanvalia

Rahu milia kalgivalia

The Khalsa rejoices today

How I long to have a vision of you

Show me yourself, fill me with joy

O plumed one, come meet me today!

O here comes the plumed one

Caresses me tenderly around his feet

You who attached me, do not leave

O plumed one, now stay with me!

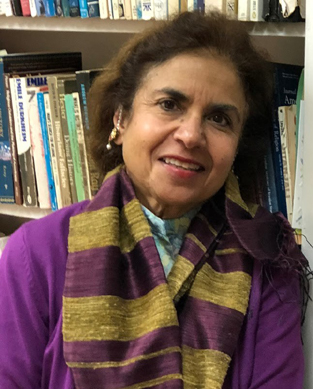

The citations in this essay are from my father Professor Harbans Singh’s biography Guru Gobind Singh, published in 1966 for the 300th birth centennial of the Guru. It has been republished by the Bhai Vir Singh Sadan (New Delhi). Not only was the book translated into most Indian languages, its Sanskrit translation won the coveted Sahitya Akademi award.

(The author is Crawford Family Professor & Chair of the Department of Religious Studies, Colby College, Waterville, ME. 04901, USA