Manipur needs moral leadership and genuine outreach by the highest offices, and not political and insincere apologies

“With no major restructuring or reimagining of the governance structure in Manipur envisaged, what it needs desperately to heal the societal divide (beyond more security personnel and fencing of borders, which must be done, in any case) is some honest soul-cleansing, a la ‘Truth and Reconciliation’, as was done in the aftermath of the ended Apartheid (White Rule) in South Africa, when portents of bloody revenge were inevitable.”

Official apologies can be powerful instruments to heal societal wounds, rectify policies and reignite hope for future unity. They can conclusively redress and reassure the disaffected to invest in another chance to normalize. However, for an apology to work, it needs to be sincere and not political.

One of the most restorative apologies in modern history is Kniefall von Warschau or the ‘Warsaw Kneel’, with West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s sudden and spontaneous gesture of genuflection before a war memorial in Poland to symbolically atone for Germany‘s past with Poland. Brandt reflected on the poignant moment: “At the abyss of German history and under the weight of millions of murdered people, I did what people do when language fails.”

The impact of the sincere apology without any unnecessary context or defensiveness was immediate. The clear courage and dignity in Brandt’s apology overcame the murky past and ushered in a new era of trust.

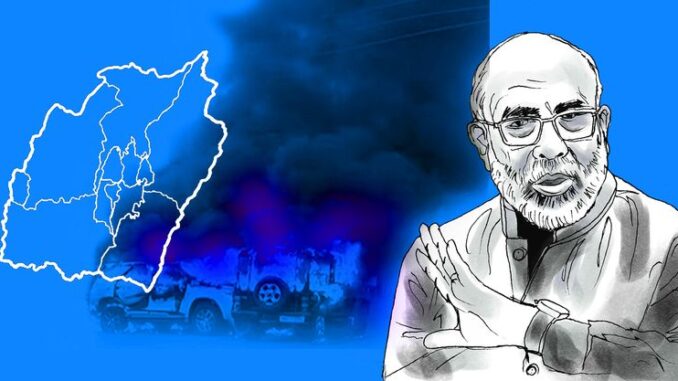

Recently, the deeply fractured, polarized and largely unacknowledged realm of Manipur re-entered the national imagination with a supposed ‘apology’ by its Chief Minister, who has presided over its slide since violence erupted in May 2023. Questions about the sincerity of the apology abound. Did it tantamount to taking ownership and accountability? Was it unequivocal? Did it resort to rote whataboutery and blame-shifting? Did it include acknowledging missteps and, therefore, rectification of outlook? Or, was it just a mealy-mouthed political statement, essentially implying more of the same, going forward?

The CM’s statement clearly lacked both personal ownership (as it pandered to generalities) and empathy, as he said perfunctorily, “Whatever happened has happened. We have to forgive and forget the past mistakes and make a new beginning.” As if on cue, and seemingly oblivious to reality, he added incredulously: “The Centre provided enough security personnel and funds”!

This begs the question that if there was no shortage of support from the Centre, why has the situation deteriorated dangerously? Was it, then, a shortage of governance intent or capabilities? Either way, an unforgivable shortcoming, if any sincerity was implicit. The final straw came with the CM blaming the previous governments (from opposition parties) for the prevailing situation, thereby effectively absolving himself and his governance from the need for any remorse.

Weeks earlier, the Union Home Ministry had issued its annual report on Manipur which highlighted a laundry list of measures taken, including personnel, financial, material, and detailed an earlier visit by the Home Minister to end the strife and disaffection. The language was almost self-patting, “The central government took a series of immediate and sustained actions to handle the situation.”

But what was not mentioned in the report or in the CM’s purported ‘apology’ was the fact that the societal divide has only worsened and the resultant violence increased.

As the face and perception of Meitei majoritarianism (against minority Kukis), the CM could have been more specific in defining who he sought to ‘forgive’ and what he wanted others to ‘forget’ in his ostensible ‘apology’. After all, it was only a political ‘apology’.

With no major restructuring or reimagining of the governance structure in Manipur envisaged, what it needs desperately to heal the societal divide (beyond more security personnel and fencing of borders, which must be done, in any case) is some honest soul-cleansing, a la ‘Truth and Reconciliation’, as was done in the aftermath of the ended Apartheid (White Rule) in South Africa, when portents of bloody revenge were inevitable.

With a complex, polarized and contested past (much like Manipur), South Africa, too, could have regressed to an explosive us-versus-them rhetoric, but for the sagacity and wisdom of the leadership under ‘Africa’s Gandhi’, i.e., Nelson Mandela.

Like the inclusive spirit of unity-in-diversity, as enshrined in the constitutional “Idea of India“, the South African leadership had chosen to valourise and posit their own civilizational concept of ‘Ubuntu,’ which is predicated on the interconnectedness of humankind. This approach is especially important as it offers a fresh and real chance to come clean by seeking forgiveness over prosecution, unlike the spirit prevailing in a solely militaristic approach, as is visible in Manipur.

If one comes from a more unbiased and progressive outlook that in any conflict, excesses or wrongs are committed by all sides (as opposed to binary ‘othering’, as is the wont in India these days), then a sense of restorative justice prevails.

Importantly, in the South African experiment under Truth and Reconciliation, the corrective action was not implied for ‘Whites’ only, but also onto ANC (African National Congress) cadres, who, too, had committed excesses. Individuals seeking amnesty came clean on human rights violations that they had perpetuated with the aim of restoring the victim’s dignity and seeking forgiveness.

A natural outcome of ‘bringing out the truth’ has a reconciliatory and forward-moving effect that cannot be achieved with retributive justice, as there are layers after layers to ‘truths’ in such places. A majoritarian spirit of ‘victor’s justice’ is avoided. In Manipur, one side definitely imagines the State to be favoring the other. Importantly, this process does not preclude justice from running its course if the magnitude and brutality (and also non-acceptance) prevails amongst parties on specific instances.

What Manipur needs is a total reconstruction of its society (and narratives). That can only emerge if the recent past is opened to inform the distraught populace on both sides about what really happened in order to accept, forgive and heal the same for a collective future. As only a wise statesman and not just a politician, Nelson Mandela could say: “All of us, as a nation that has newly found itself, share in the shame at the capacity of human beings of any race or language group to be inhumane to other human beings. We should all share in the commitment to a South Africa in which that will never happen again.”

Manipur needs such moral leadership and genuine outreach by the highest offices, and not political and insincere apologies.

(The author is a retired Lt. General of the Indian Army)

Be the first to comment