BOSTON (TIP): Stanford scientists have developed a new software tool which will enable energy companies to calculate the possibility of triggering manmade earthquakes from activities associated with oil and gas production.

Oil and gas operations can generate significant quantities of “produced water” – brackish water that needs to be disposed of through deep injection to protect drinking water.

Energy companies also dispose of water that flows back after hydraulic fracturing in the same way.

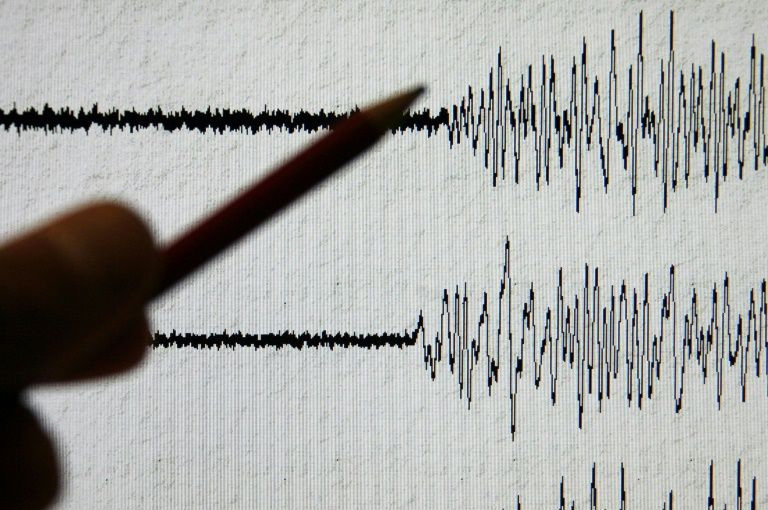

This process can increase pore pressure – the pressure of groundwater trapped within the tiny spaces inside rocks in the subsurface – which, in turn, increases the pressure on nearby faults, causing them to slip and release seismic energy in the form of earthquakes.

“Faults are everywhere in the Earth’s crust, so you can’t avoid them. Fortunately, the majority of them are not active and pose no hazard to the public,” said Mark Zoback, professor at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy at Environmental Sciences.

“The trick is to identify which faults are likely to be problematic, and that’s what our tool does,” said Zoback.

The newly developed Fault Slip Potential (FSP) tool uses three key pieces of information to help determine the probability of a fault being pushed to slip.

The first is how much wastewater injection will increase pore pressure at a site. The second is knowledge of the stresses acting in the earth.

This information is obtained from monitoring earthquakes or already drilled wells in the area. The final piece of information is knowledge of pre-existing faults in the area.

Such information typically comes from data collected by oil and gas companies as they explore for new resources.

Researchers have started testing their FSP tool in Oklahoma, which has experienced a sharp rise in the number of earthquakes since 2009, due largely to wastewater injection operations.

Their analysis suggests that some wastewater injection wells in Oklahoma were unwittingly placed near stressed faults already primed to slip.

“Our tool provides a quantitative probabilistic approach for identifying at-risk faults so that they can be avoided,” said Rall Walsh, graduate student at Stanford.

“Our aim is to make using this tool the first thing that is done before an injection well is drilled,” Walsh said.