Is the 7-medal tally – the highest ever – in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic games reason enough for one of the emerging economic powers to tell the world that it has its second individual gold medal winner in its 93-year history of Olympic participation?

Are we happy or satisfied withwhat we have achieved in sports since Independence 75 years ago? Fortunately, celebrations that followed Tokyo games have come on the eve of the 75th anniversary of our Independence.

The British basically introduced hockey, cricket and golf. They all had their origin in Army Cantonments. While the British generally encouraged the local people’s participation in hockey and cricket, golf was restricted only to the officers’ category. Since then, it has remained an elite and status sport.

India is in celebration mode. An Olympic medal in athletics – the first in 93 years – and return to the podium of the men’s hockey team after 41 years may be prime provocations for the sports lovers of this one of largest populated liberal democracies to go overboard to rejoice over accomplishments in playing arenas. Never has the country had medals of all three colors in its tally from one Olympic game.

But is the 7-medal tally – the highest ever – in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic games reason enough for one of the emerging economic powers to tell the world that it has its second individual gold medal winner in its 93-year history of Olympic participation?

Incidentally, the US has taken its gold medal tally in Olympics past the 1060 mark while India has touched the double digit. Of 10 gold medals, eight have come from hockey alone. Fifteen of the 35 Olympic medals won by India have come from hockey alone.

Are we happy or satisfied with what we have achieved in sports since Independence 75 years ago? Fortunately, celebrations that followed Tokyo games have come on the eve of the 75th anniversary of our Independence.

Olympics are a vital parameter to judge a nation’s progress in sports. There are still 70-odd nations who are still without an Olympic medal. But those are the nations torn by strife, poverty, corruption, and natural calamities.

India started well. A year after Independence, it won its first gold medal in hockey in London and four years later, wrestler KD Jadhav got first individual medal, a bronze, in Helsinki. In 1960, we were close to winning our first medal in athletics as Flying Sikh Milkha Singh not only created a new Olympic record but missed a possible bronze by a whisker. In Tokyo, hurdler Gurbachan Singh Randhawa was also well within the reach of an Olympic medal at Tokyo.

The pace was, however, lost. After 1964, we lost our guaranteed gold in hockey apart from silver in Rome, 1960) and then came 1972, we got our second successive bronze in hockey before getting blanked out of the medals tally. The golden return to the medals tally was restricted to the boycotted 1980 Moscow Olympic games where we got hockey gold back.

Subsequently, we got in the habit of returning home empty handed – 1984, 1988, and 1992 – before a bronze in tennis (Leander Paes) put us back in the medals tally. K. Malleshwari maintained the tradition with a bronze in weightlifting in Sydney (2000) before Major Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore shot for the country’s first individual Silver in Athens in 2004.

It appears we are now back in the year 2008. The Olympic games had returned to Asia and India got its first ever individual gold medal in shooting. Abhinav Bindra shot well to finish at top in 10 m Air Pistol event to make up for his loss of concentration in the final of the same event four years earlier in Athens. India had multiple medals for the first time since 1952. Boxer Vijayender Singh and wrestler Sushil Kumar (bronze) were the other winners.

London was perhaps the previous best where India got six – two silver and four bronze medals. Shooter Vijay Kumar and wrestler Sushil Kumar with silver medals gave Indians every reason to cheer about as they were joined by Saina Nahewal (badminton), Mary Kom (boxing), Yogeshwar Dutt (wrestling) and Gagan Narang (shooting).

There was a huge drop in Rio where Indian ended up with a silver in badminton (PV Sindhu) and a bronze in wrestling (Sakshi Malik).

On careful analysis of India’s progress in Olympic games, it appears uneven, lopsided, and least indicative of a representative India. Why is it so? Why is India still among those who ran? Why does India not have many world champions reflecting its huge human resource base?

Let us analyze Indian sports.

What is India’s national sport?

In 2009 as a journalist working in The Tribune, I conducted an investigation that had startling revelations. A black and white picture of a basketball hoop

Description automatically generated with low confidence If you believe cricket is the most popular sport in India and hockey has been our national sport, you are wrong and misinformed. India’s number one sport is golf.

Golf takes the highest share of public funds as three hockey or equal number of cricket stadiums can be made from the money needed to raise a new 18-hole 72-par international standard golf course. Already the number of international golf courses is three times more than the equivalent hockey or cricket centers that can hold international events in the country.

The number of golf courses has multiplied four to five times during the last 20 to 25 years with a few private players chipping with their expertise in south India. International standard facilities in no other sport have ever doubled during the same period.

There are more facilities for golf than for any of the Olympic sports in the country. Athletics, football, badminton, boxing, wrestling, shooting, tennis come nowhere near hockey or cricket, what to talk of golf. For the ardent golflovers, 2016 was a big year as the sport was included in the 2016 Olympic games.

Aditi Ashok, who finished an impressive fourth in Tokyo, had competed in the inaugural event in Rio as an 18-year-old budding golfer. At 23, she is already a veteran of two Olympic games. Also in Tokyo was another special golfer Diksha Dagar.

Though a game of the rich and affluent, especially those belonging to higher echelons of civil services, defense forces and captains of business and industry, golf remains far from a common man sport. Interestingly, the percentage of those seeking a career in golf does not run beyond a few thousands in a country of 1.4 billion people.

Even the laurels won by golfers in international competitions, including world championships, continental championship, professional circuits, Commonwealth Games and Asian Games, are too little to be comparable to those of common man sports like hockey, football, track and field, boxing, wrestling, weightlifting, badminton and even elite sports like tennis and squash.

The British basically introduced hockey, cricket and golf. They all had their origin in Army Cantonments. While the British generally encouraged the local people’s participation in hockey and cricket, golf was restricted only to the officers’ category. Since then, it has remained an elite and status sport.

Hockey, cricket and football were patronized by lower middle and middle class and as such had phenomenal rise in following. But the facilities did not match their growing popularity. Even after Independence, the government did little to bridge the gap between the popularity of these sports with the demand for levelled playfields.

This is one reason that one finds cricket matches going on in streets, all available even uneven open spaces, growth of golf courses has been satiating the demand from golfers. An average golf course with a club house and a bar has 800 to 1,000 members to make the number of golf enthusiasts reach about 5,00,000 to a million. This is perhaps the highest per capita availability of golf courses compared to the per capita availability of equivalent infrastructure in hockey, football, cricket or track and field.

Football, volleyball and basketball, in spite of being the cheapest ball sports, are far low on the per capita playing facilities list. Even if the facilities have been created, they are either out of reach of a common man or are not maintained properly for want of funds and government patronage.

Significantly, new towns and cities have ambitious plans for developing golf courses, both in private and public sector, but none of the new colonies coming up throughout the country have any provision for basic level playfields. Though India dreams of “sports for all,” the neglect of common sports indicates otherwise.

It is money that works. Since returns from golf courses can be expected together with adequate hefty membership fee, the private sector has joined in. But this is not the case with similar infrastructure or stadia of hockey, football, track and field.

Hoshiarpur may have produced several international football stars (Manipur is world known football nursery) including Jarnail Singh (he was from a nearby village Panam), but it does not have a football stadium of international specifications. It has an 18-hole golf course at the Police Recruitment Training Centre at Jahan Khelan.

Phillaur’s Punjab Police Academy also has a golf course. In Jalandhar, while the police have 18 greens in its golf course, the only recognized golf course in this sports city is that of the Army.

Chandigarh and its periphery are now dotted with golf courses at Panchkula, Chandi Mandir and the Sector 6 golf courses. Besides, it has in its immediate Punjab periphery a private golf course. There is a golf Range in Mohali.

Panchkula also has its own golf course in addition to the one Army has at Chand Mandir cantonment.

Going by numbers and popularity, no sport can come anywhere near cricket. This sport with its latest hit, instant 20-20 version, may have made it the Number One entertainer in the country. Yet it comes nowhere near golf in infrastructure.

There are only 30-odd international level cricket centers of which at least 20 can hold Test matches in the country. A rough estimate reveals that 20-30 per cent of the population must have enjoyed playing this sport. It has pushed behind hockey, once acknowledged as India’s national sport. It is only hockey that has given eight Olympic gold medals since 1928. And the number of hockey stadia with synthetic surfaces or astro-turf, after installation of 12 new artificial playfields by the next year-end, will swell to 29.

The number of international centers for cricket and hockey may be just around 30 each. Though Tokyo marked the return of hockey to podium in Olympics as earlier in 2018 India won the World Cup for juniors.

In 2008, India failed to qualify for Olympic Hockey competition in Beijing for the first time in 80 years and in 2006, it failed to make the medal round in the Asian Games.

Though there are 18-hole golf courses in the country, not even 0.01 per cent people of the country play golf. There are as many as 80 golf courses of 18-hole 72-par specifications and an equal number of nine-hole courses.

The defense forces that have lost out in most of the sports in which they used to dominate at national level have at least 15 full-fledged 18-hole 72-par golf courses. The police, the Border Security Force, the Oil and Natural Gas Commission and other public sector undertakings, too, have their own golf courses.

Golf architects maintain that given the present market parameters, a new 18-hole golf course will cost at least three to four times an international standard cricket or hockey stadium. Of recent hockey stadia built worldwide, the cost hovers between $1.8 million and $2.5 million. The maintenance cost of a golf course is five to 10 times that of a hockey or cricket stadium.

One of the biggest cricket stadiums of the world was inaugurated some years ago when the US President Donald Trump visited Ahmedabad in Gujarat.

While the number of privately owned golf courses is not very large, the remaining are all on public or government land. Beneficiaries, mostly senior civil servants and defense officers, basically come from the service class.

Industrialists, businessmen and technocrats make up for only 15 to 20 per cent of the total membership of these clubs. Intriguingly, sports in the country are controlled at the district, state and national level by those who are themselves golf addicts.

The progress of golf looks impressive. But what about sports common people play?

For the purpose of analysis and to facilitate understanding of Indian scenario, sports can safely be segregated into three groups – team games and sports, sports of the elite and sports for the common man.

As mentioned earlier, the British were intelligent in choosing sports and their target groups of acceptance. Hockey, for example, was chosen for lower middle class. They chose villages around their cantonments in Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai), Jhansi, Bhopal, Jalandhar, Meerut and a few other places. The game had instant acceptance and within a few years the results were startling. Players of Indian origin started dominating all hockey teams.

It was this phase that threw up on Indian horizon hockey greats like Major Dhyan Chand, his brother Roop Singh, Adivasi leader Jaipal Singh, Thakur Singh, and Col Gurdev Singh, besides several others. They were so skillful and talented that they easily walked into Indian teams that left the shores of the country to participate in Olympic games for the first time in 1928 and subsequently in 1932 and 1936. British were so envy of them that they withdrew their teams from the Olympic games saying that they were not to face their own colony on playfields during 1928, 1932 and 1936 Olympic games. What the British did was provide even playfields, cheap and affordable hockey sticks and balls. While many played the sport barefoot, others had normal canvas shoes that were given to army jawans for their normal exercise and fatigue.

After Independence, things changed rapidly. Hockey base started shrinking and India’s supremacy was seriously challenged, first by Pakistan, and then Europe followed by Australia and New Zealand. In 1960, India lost its hockey supremacy to Pakistan and could win gold only twice afterwards – 1964 Tokyo and 1980 Moscow. Now in Tokyo India won a Bronze, it last one in Munich in 1972.

Same has been the story of women’s hockey. One family of a college peon producing five internationals, including captain of the country’s first Olympic team in 1980, Rupa Saini, is unprecedented. Besides Rupa, Prema, Krishna, Swarna all played for India. That was the time we had great hockey players like Geeta Sarin, Rekha, Margaret Toscano, Harpreet Shergill, Baljit Bhatti, Lata Chinana, Kiran Malhotra, Kiran Mehta, Chanchal Randhawa, Balwinder Kaur Bhatia, Varsha Soni, Nazleen Madraswala and tallest of them all Ajinder Gurcharan Singh.

Schools and colleges used to pride in their strong teams, not only in men and women’s hockey, but also in volleyball, basketball, football, handball, besides good players in badminton, table tennis, track and field, boxing, weightlifting, wrestling and swimming.

In Football, India not only remained Asian champion but also played in Olympics soccer, both in 1956 and again in 1960. But where is India in soccer now. Some great footballers like Jarnail Singh, Chuni Goswami, S. Banerjee, Inder Singh, Gurdev Singh Gill, Peter Thyagarajan, Parminder Singh, Sukhwinder Singh, Lehmber Singh, Ravi Kumar, Manjit Singh, Narinder Gurung, Bal Gurung, Harjinder Singh, are some names that dominated Indian landscape in 70s and 80s.

Though some of the famous football clubs like East Bengal, Mohun Bagan, Mohammedan Sporting still dot the Kolkata dateline, yet they have been losing fast their star appeal in the rest of the country. Punjab’s famous football teams – Leaders Club (of Mr DD Sehgal), JCT Mills, Phagwara, and even teams like Border Security Force, Punjab Police and Punjab State Electricity Board have either faded into history or are just a skeleton of their healthy past.

The story is no different in volleyball and basketball.

Great names like Khushi Ram, Hanuman Singh, Manmohan Singh, TS Sandhu, Sajjan Cheema, Parminder Singh Cheema and several others were the national heroes in Basketball in which India used to hold a respectable place in Asian Basketball Federation’s annual events.

India was once a superpower in Asian athletics with some outstanding track and field stars, including Flying Sikh Milkha Singh, Makhan Singh, Ajaib Singh, Leo Pinto, Sriram Singh, Shivnath Singh, Hari Chand, Charles Borromeo, Mohinder Singh, Mohinder Gill, Labh Singh, Parduman Singh, Parveen Kumar, Jugraj Singh, Bahadur Singh, Baba Gurdip Singh, Geeta Zutshi, Manjit Walia, Kamaljit Sandhu, PT Usha, Shiny Abraham, Valsamma,

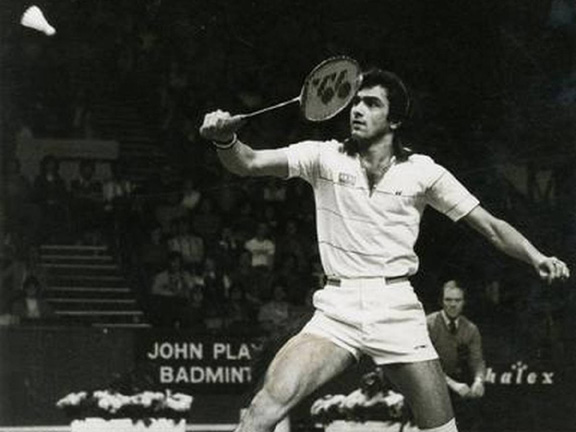

Badminton had some of stalwarts like Dinesh Khanna, Satish Bhatia, Devinder Ahuja, Partho Ganguly, PG Chengappa, Ami Ghia, Kanwal Thakur Singh, Madhumita Ghosh, Amita Kulkarni before Parkash Padukone, Syed Modi, and P. Gopichand emerged on the horizon.

Parkash Padukone became the first Indian player to win an all-England title in 1981. Later on, Syed Modi also won this prestigious grand slam event.

Manjit Dua, Manmeet Singh, Vilas Menon, G. Jagan Nath, Indu Puri, Veenu Bhushan were once upon Indian Table Tennis stars.

Admittedly, they did not win many medals in big or prestigious sporting events like Asian Games, Commonwealth Games or Olympic Games but they were mostly self-made sports stars. They worked hard and very limited facilities did not deter them from working hard and maintaining a consistent performance.

Of course, those were the days, when the country had some good sports schools, sports colleges and institutes specializing in Physical Education.

Unfortunately, they got phased out and were got replaced by sports wings, sports hostels and centers of excellence. That was the time, when the participation dropped rapidly. Schools and colleges with wings and hostels had all low level of professionalism as the institutions lured good players with certain concessions, perks. Other intuitions with no wings and hostels lost interest in raising their teams as they found themselves adequately unequal to compete against “professional outfits of hostels and wings”.

The 1996 Atlanta Olympic games was a turning point.

Though India had excellent track record in tennis with players like Ramanathan Krishnan, Jaideep Mukherjee, Premjit Lall, S. Mishra and Jasjit Singh, followed by Amritraj brothers – Ashok and Vijay – and Ramesh Krishnan donning colors with excellent track record in not only great grand slams but also in Davis Cup.

Tradition set in motion by them was followed by equally talented Leander Paes and Mahesh Bhupathi as they had many grand slam titles under their belt. They defeated the world’s best doubles teams and put India at top. And Leander capped it with a bronze medal in men’s singles in 1996 Atlanta Olympic games, the year the games were thrown open to professionals. Leander lost in the semis to the ultimate winner Andre Agassi of the US.

Sania Mirza was the first Indian woman tennis player to win grand slams and get the highest ranking in women’s doubles. She missed a bronze. Medal in Rio (in partnership with Rohan Bopanna) and made a first round exit in Tokyo in partnership with Ankita Raina.

A strong message went down the line.

Parents keen on getting their wards to sports got inspired by the Leander’s feat. After a gap of 44 years, Leander became only the second Indian to win an individual medal in Olympics. It was the beginning and since then individual medalists have started dotting Indian sports scene.

This change took first turn for gold in 2008 (Beijing, 10 m Air Rifle shooting Abhinav Bindra) and again now (Tokyo 2020, Javelin throw for men, Neeraj Chopra).

When Abhinav won first individual gold in shooting in 2008, it was the country’s second medal in shooting. Four years earlier, Major Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore had won a silver in Athens.

Shooting was not new to Indians competing in Olympic games. For a long time, India had been sending shooters, mostly from Royal families, to try luck and get the country a place among medalists.

Raja Karni Singh, a trap shooter, participatedin five consecutive Olympics, starting with Rome (1960) and Moscow (1980) as his last.

To date only four Indian shooters – Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, Abhinav Bindra, Vijay Kumar and Gagan Narang – have been successful in winning Olympic medals.

One possible reason for India’s down slide in sports had been the diminishing role of sportsmen from defense forces (Services). Milkha Singh hawked headlines in late 50s and early 60s, he was part of Indian Army.

If Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore won the country’s first ever individual medal (Silver) in shooting, he was from Indian Army. Vijay Kumar was also from the Army when he took the Olympic silver in London.

Now when Neeraj Chopra has become the new national hero with an Olympic gold, he comes from Indian Army. Two other sportsmen from the Army who competed in Tokyo 2020 had every reason to feel satisfied with their performances.

Boxer Satish Kumar became the first Indian boxer to clear the first round in the super heavyweight category while Deepak Punia lost the battle for bronze in 86 kg freestyle wrestling.

Looking back, if Indian boxers did well in Olympic games, they mostly came from Services. The last medal hopeful Gurcharan Singh lost a controversial bout to get denied a possible medal. Kaur Singh and Jaspal Singh had been other boxers from Services to do well.

It is pertinent to point out that Services need to play the role it had been playing in promoting and developing sports. There used to be a time when the best hockey goalkeepers used to come from Services. Boxers, wrestlers, athletes and hockey players coming from the defense forces always occupied a respectable position in Indian contingents competing in prestigious international events. This has to be restored for the larger interest of Indian sports.

Golf is alright but other sports must not be ignored. Let Services once again take upon itself the onerous responsibility of giving sports its due.

Overseas Indians in sports

*Wrestler Amar Dhesi, water polo player Gurpreet Sohi and hockey players Sukhpal Panesar, Brandon Pereira, and Kegan Pereira were chosen to don Canadian colors in Tokyo.

*Gurpreet, incidentally became the first ever woman athlete of Indian origin to represent Canada in Olympic games.

*Table Tennis duo of Kanak Jha and Nikhil Kumar have been chosen to play for the USA in the Tokyo Olympic games.

Though none of these Indians could make a podium finish in Tokyo 2020 still they did enough to prove their credentials.

Samir Banerjee won the boys singles title in the 2021 Wimbledon

The year 1984 was a tumultuous year for the Punjabi community in general, and the Sikhs in particular. It may not be easy for anyone to put behind the dastardly and tragic events in the union capital that rocked not only Punjab but also the entire Sikh community elsewhere. As this minute minority was drowning in gloom, two overseas Punjabis – Alexi Singh Grewal and Kulbir Singh Bhaura – provided the silver lining by telling the world how enterprising they were. Not only they entered the history annals as first overseas Indians to win Olympic medals, but they also set a new trend in motion that has been kept afloat by enterprising Indian diaspora ever since.

Their heroic deeds scripted a new chapter of “Brand India”. Before the year 2016 ended, yet another overseas Indian – Rajeev Ram – kept the “Brand India” flame alive by winning an Olympic medal, a Silver, in the Rio Olympic games.

Contribution by the overseas Indian community cannot be undermined for its diminutive size as it has won the cockles of many a heart in the contemporary sports world.

In December 2016 when a field hockey team from Canada went to play in the Junior World Cup Hockey Tournament in Lucknow, 11 of its 16 members were of Indian origin.

These players –Brandon Pereira, Harbir Sidhu, Parmeet Gill, Rohan Chopra, Rajan Kahlon, Kabir Aujla, Balraj Panesar (captain), Ganga Singh, Gavin Bains, Arshjit Sidhu and Iqwwinder Gill – need to be complimented as they self-financed their participation in the prestigious Lucknow tournament.

And the Australian team, too, had one player of Indian origin, Kiran Arunasalam. It is after a long time that any player of Indian origin played for Australia in hockey.

Overall, the overseas Indian community has done exceedingly well in the world of sports, including Olympic games, Commonwealth games and cricket.

You name any sport in which the overseas Indian community has not won laurels for the countries of its present abode. There are 17 countries, including Canada, the US, Australia, Malaysia, England, Kenya, Uganda, and Hong Kong, that have been represented by overseas Indians in Olympic games. It is no mean achievement.

Kulbir Bhaura, who represented Great Britain in field hockey, has been the only overseas Indian to have two Olympic medals to his credit, a bronze in Los Angeles and a gold in Seoul.

Then there is Shiv Jagday. A former Indian Universities color holder: he had the distinction of working as National Coach of Field Hockey Canada. He also coached the US national team besides being on the panel of the select FIH coaches. His son Ronnie Jagday played for Canada in the Sydney Olympic games.

One must not forget the contribution of Malkiat Singh Saund who was one of the best forwards of the 1972 Munich Olympic games. Malkiat represented Uganda. Now he is settled in England.

Sutinder had the distinction of leading England in one match in the Mumbai World Cup Hockey Tournament in 1981-82. He played for England and Great Britain for several years.

If Australia is a world power in field hockey, it is all because of efforts of Pearce brothers who immigrated to Australia from India and represented their new country of abode in the Olympic games.

Hardial Singh Kular, besides playing for Kenya, also rose to be the Vice-President of the International Hockey Federation (FIH). He was one of many Indian expatriates who represented Kenya in 60s and 70s of the last centenary. He stands tall in sports administration.

Avtar Singh Sohal is the only player to have played in four Olympic games and captained his national team – Kenya – in two. A great deep defender, He has been a pillar behind the Kampala’s Sikh Union Club that has recently acquired a floodlit synthetic surface for hockey.

Alexi Grewal, the first overseas Indian, to win an individual Olympic gold medal. In the 1984 Olympic games, he won the road race event in cycling in style. His father, Jasjit Singh, a Sikh, had migrated to the US. Interestingly, Alexi Grewal’s individual gold, though for the US, came 24 years before Abhinav Bindra won India’s first ever-individual gold medal in Olympic games.

The latest from the overseas Indian community to get on to the Olympic medalist list was tennis player Rajeev Ram who won a silver medal in mixed doubles in the 2016 Olympic games in Rio.

While the overseas Indians have done the country and the overseas Indian community proud, the Indian government is yet to reciprocate. Though it started organizing Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (PBD) where outstanding members of the overseas Indian community were felicitated, sportsmen and women did not get their due. The PBH celebrations have been largely discontinued. Covid 19 pandemic may be a contributing factor for the cancellation of the event for the last two years.

Besides Alexi Singh Grewal, Kulbir Singh Bhaura and Rajeev Ram, there are many other sportsmen and women, who have done the overseas community and India proud.

Rajeev Ram has to his credit a silver medal. In partnership with Venus Williams,

Rajeev Ram finished runners-up in the mixed doubles event in Tennis. Thirty-two- year-old Rajeev is first generation American. His parents moved to the States in 1981 and Rajeev was born in 1984.

Rajeev won his first major Tennis title in Chennai in 2009. Rated as one of the top doubles players in tennis, silver in Olympics has been his highest achievement. In the semi-finals, Rajeev and Venus Williams defeated Sania Mirza and Rohan Bopanna. After Rajeev Ram, another athlete of Indian origin doing well for a country other than India is shuttler Rajiv Ousef. Born in an Indians dominated Hounslow area in England, Rajiv qualified for quarterfinals of men’s singles in Rio. On his way to the last eight, Rajiv had beaten Tommy Sugiarto of Indonesia, Sasaki Sho of Japan and Koukel Petr of Czech. At 30, this was perhaps best performance in a major sporting event. He had won a silver medal in the 2010 Commonwealth games in New Delhi.

Cricket is a game that every person of Indian origin follows. Monty Panesar scripted a new chapter when he became the first turban-wearing player to represent a country other than India in Test cricket. Monty played for England. Ravi Bopara followed him.

(The author is a senior journalist. He can be reached at prabhjot416@gmail.com)

Be the first to comment