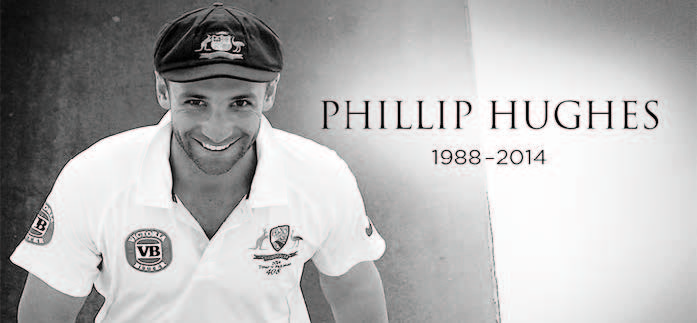

You didn’t have to know Australian batsman Phil Hughes to be shaken by the news of his death after a twoday battle in hospital upon being hit by a cricket ball in a Sheffield Shield game at the Sydney Cricket Ground. The world of cricket – players, coaches and other support staff, match officials, administrators, media persons and fans alike – will be united in grief. Over the past two days, there was hope that the kiss of life that Dr Orchard gave Hughes on the hallowed cricket pitch on Tuesday would have worked in his favour.

There was expectation that Hughes’ will to battle for life would be as strong as the determination that fetched him two hundreds in just his second Test. There was faith that the doctors would help him pull through. It took but a moment – and a text message from a friend in Australia – for those positive emotions, fuelled by an outpouring of prayers by the cricket world at large, to change to shock. Of course, the wise have told us that death is the most certain event in one’s life. But such philosophy is of little consolation when the end comes as an accident with tragic overtones.

More so, if the victim is in the flush of youth. Surely, 25 is no age to die. Surely, a blow received on the cricket field is not a reason to be dead. There is no doubt that Hughes’ death will cloud the impending Test series between Australia and India. You can expect players from both sides to have a grave demeanour for quite some time. As we pick up the pieces and try to move on, the players will be the most challenged by paradoxical needs to be aggressive and yet sombre; combative and yet intensely serious. We have seen the spectre of death loom over cricket and the world of sport -New Zealand left Sri Lanka because of a bomb blast outside the team hotel in Colombo in 1987. England played in Mumbai in 1993 weeks after serial bomb blasts. Six years ago, England returned after a short break caused by a terrorist attack in Mumbai.

Other grim memories come flooding back.

A strange scorecard entry: ‘Abdul Aziz absent dead’ from the Qaid-E-Azam Trophy final in Karachi in 1959. The decline of Hyderabad batsman CL Jaikumar after what seemed to be a good start to a first-class career after he was felled by a Robin Singh bouncer in a 1990 Ranji Trophy game in which he had made 169 in the first innings and was on 42 in the second. But the worst recall is that of former India opener Raman Lamba’s death in February 1998. One can feel the shivers down the spine when thinking of a dark, cold, rainy night when Lamba’s body was brought to Delhi from Dhaka.

Instead of walking through the arrival hall, he returned in a coffin in the cargo terminal with a few family and friends in attendance. Hughes’ death has lessons, not the least being the establishment of emergency response teams at venues. Perhaps, with greater monies coming in to cricket, the international centres should go beyond from having an ambulance on stand-by to exploring possibilities of instituting a medical centre within the premises so that no time is lost in providing the best aid to an injured player. May the world of cricket grieve together as one but long may the game remain beautiful as we have known it.

For it is but a reflection of the lives we live, a heady mix of pain and pleasure, agony and ecstasy, joyous and grim and all that lies between. But, above all, may Phillip Joel Hughes’ soul find lasting peace

Be the first to comment