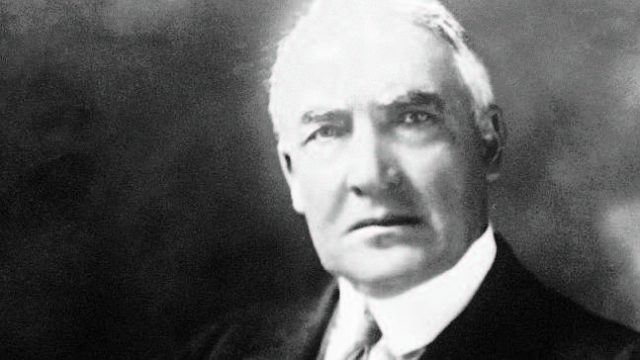

WASHINGTON (TIP): Long before Lucy Mercer, Kay Summersby or Monica Lewinsky, there was Nan Britton, who scandalized a nation with stories of carnal adventures in a White House coat closet and endured a ferocious backlash for publicly claiming that she bore the love child of President Warren G. Harding.

Now, a century later, genetic tests confirmed that Britton’s daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, was indeed Harding’s biological child, offering new insights into the secret life of America’s 29th President. The revelation has also roiled two families that have circled each other warily for 90 years, struggling with issues of rumor, truth and fidelity. Even now, the President’s family members remain divided over the matter, while some descendants of Britton remain resentful that it has taken this long for her credibility to be validated.

“It’s sort of Shakespearean and operatic,” said Dr. Peter Harding, grandnephew of the President and one of those who instigated the testing. The Nan Britton affair was not the first time a President was accused of an extracurricular love life, but never before had a self-proclaimed presidential mistress gone public with a tell-all book.

While some historians dismissed Britton’s account, it remained part ofpopular lore. Britton, who was 31 years younger than Harding, had a harder time proving her relationship, because she had destroyed her own letters with him at his request and because his family insisted he was sterile. After finding Britton’s book, “The President’s Daughter,” among his father’s belongings, Dr. Harding and his cousin, Abigail Harding, decided to pursue the matter and contacted James Blaesing, grandson of Britton and son of the daughter she claimed to have conceived with the President. Testing by AncestryDNA, a genealogical website, found that Blaesing was a second cousin to Peter and Abigail Harding, meaning that Elizabeth Ann Blaesing had to be President Harding’s daughter.

The testing also found that Harding had no ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa, answering another question that has intrigued historians. When Harding ran for presidentship in 1920, segregationist opponents claimed he had “black blood.”

“I’m not questioning the accuracy of the tests. But it’s still in my mind still to be proven,” said Dr. Richard Harding, 69, another grandnephew. If the tests are valid, he added, he welcomed the new members.