“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference,” the 20th-century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr once famously wrote. Arguably, this very much sums up the United States President Barack Obama‘s foreign policy doctrine and his valuation of American priorities in various regions.

In fact, the president has been always open about the profound influence of Niebuhr’s works, affectionately declaring in an interview, “I love him. He’s one of my favorite philosophers.”

Obama saw himself as a perfect antithesis to the George W Bush administration, which combined coercive unilateralism with a missionary zeal to supposedly spread US-style democracy in the Middle East and beyond.

The Bush era disasters heavily undermined neo-conservatism, paving the way for the rise of more calibrated realists such as Obama, who appreciated the limits of US power and the virtues of strategic patience.

As the Obama administration enters its twilight months in office, questions over its legacy and long-term historical significance have gained momentum.

The most salient aspect of Obama’s foreign policy, one could argue, is his gradual retrenchment from the Middle East, where the US has been hopelessly overstretched, in favor of an accelerating pivot to Asia, where booming economies and a rising China are reshaping the global order.

Not long ago, prominent journalists such as James Traub were quick to portray Obama as a deflated, demoralized idealist, who “has been well and truly mugged by reality”.

Multiple crises, from Russia‘s annexation of Crimea to the rise of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS), seemed to have undermined the US power, and extinguished Obama’s hopeful vision of an orderly, rule-based international order.

Asia is simultaneously a region where there is the greatest opportunity for expanded trade and investments and also where the US confronts its greatest rival, China.

In the Middle East, the Arab winter and the deadlock in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations swept away the wellspring of optimism generated by Obama’s historic Cairo speech, where he unsuccessfully promised a new relationship between the US and the Muslim world. But soon it became clear that Obama had some foreign policy tricks up his sleeve.

Obama managed to pull off an improbable and highly controversial nuclear agreement with Iran, while normalizing relations with communist Cuba and becoming the first US president to visit Cuba in almost a century.

True to his early promise of reaching out to historical foes, Obama oversaw a qualitative shift in Washington’s approach to former foes such as Tehran. But as Obama admits in his long interview with Jeffrey Goldberg, he has been committed to decouple from the conflict-ridden Middle East.

Recognizing the US failures in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, where its military interventions have created failed states and havens for extremism, Obama refused to even enforce his own redline on Syria, when the Bashar al-Assad regime was accused of using chemical weapons against its own population. Clearly, he had little appetite for additional US military entanglements in the region.

Amid rising Saudi-Iranian rivalry, he has even encouraged Arab allies “to find an effective way to share the neighborhood [with Iran] and institute some sort of cold peace”, giving birth to a post-American order in the region.

Instead, Obama, who was raised in Indonesia and Hawaii, has been primarily interested in augmenting US strategic footprint in the Asia-Pacific region, where “[the US] can do really big, important stuff”, which have “ramifications across the board.”

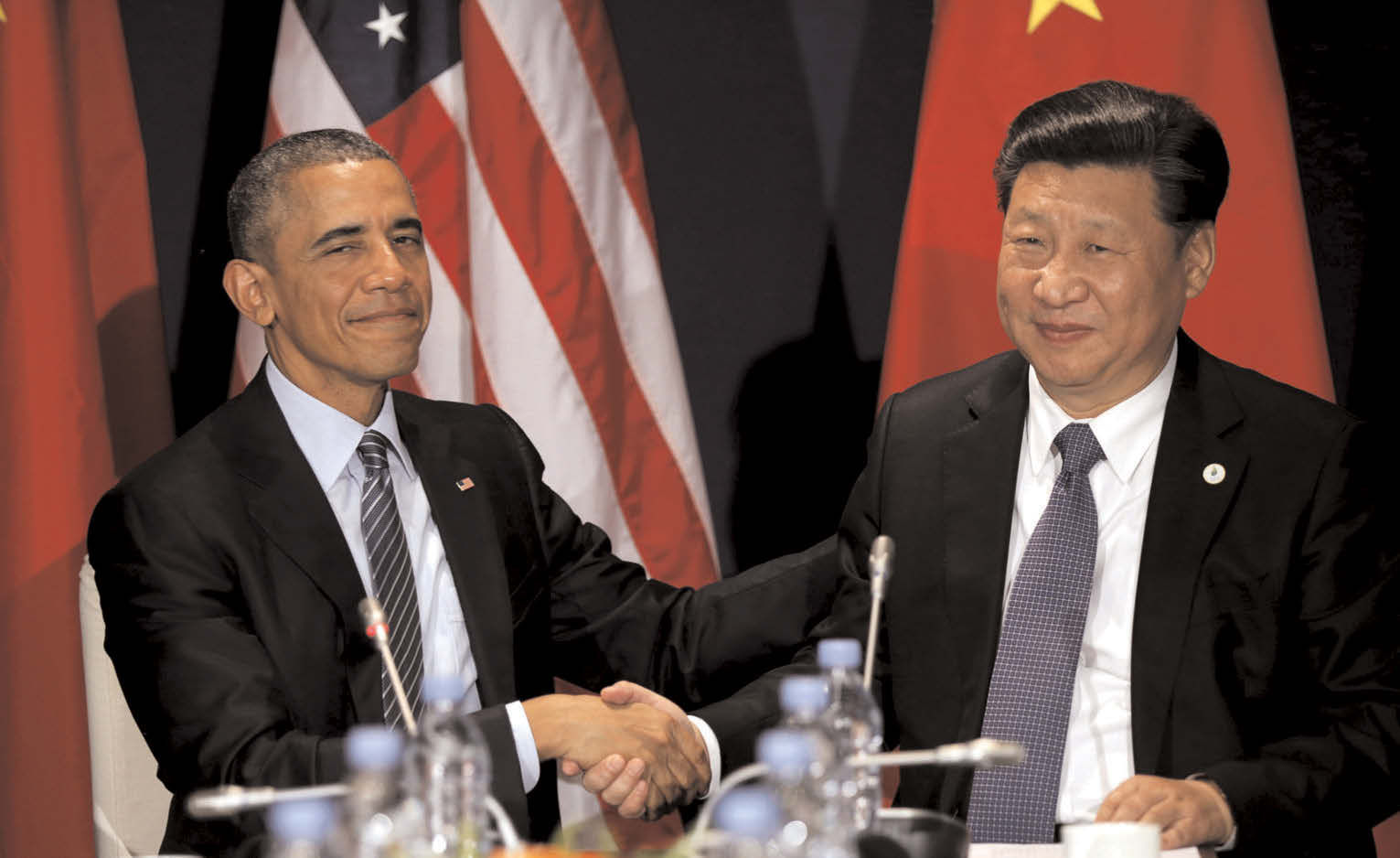

Under Obama, who has visited Asia more than any of his predecessors in recent memory, the US has established cordial ties with former foes such as Vietnam and Myanmar, built strategic partnership with key Muslim countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, upgraded high-level dialogue with China, negotiated a major regional trade pact – the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement -and overseen a major improvement in its approval ratings.

The revived interest of the US in Asia is based on a belief that “the relationship between itself and China is going to be the most critical” in the 21st century. More fundamentally, Obama believes that the future of the US and the world will be decided in the Asia-Pacific region, which is “filled with striving, ambitious, energetic people”.

Exasperated by persistent anti-Americanism in the Middle East, Obama enthusiastically cites how Asians are pragmatists who are willing to work with the US and are committed to “build businesses and get education and find jobs and build infrastructure.”

In short, Asia is, simultaneously, a region where there is the greatest opportunity for expanded trade and investments and also where the US confronts its greatest rival, China.

There are, however, concerns that the US may have missed the train, for it faces an uphill battle in maintaining its hegemony in Asia, especially as a resurgent Beijing gradually carves out a new Sino-centric order in East Asia.

In economic terms, China is the leading trading partner of almost all East-Asian countries, while it is set to transform into the pillar of infrastructure development in Asia, thanks to major development initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Maritime Silk Road plan. China is the new economic pivot around which Asia revolves.

Overseeing decades of rapid military modernization, Beijing is also progressively pushing US naval forces out of its adjacent waters, upending centuries of Western military hegemony in Asia.

Some of Obama’s likely successors are far from helpful. Demagogues such as Donald Trump, who is calling for a return to 19th-century American mercantilism, is undermining Asia’s confidence in the US and its reliability as a superpower.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether Obama’s renewed focus on the region has been enough to prevent a post-American order in Asia. Yet one should credit him for becoming the first truly Pacific president in the White House, reorienting US foreign policy from the troubled Middle East to a promising Asia. This will be his greatest foreign policy legacy.

The author is a specialist in Asian geopolitical/economic affairs and author of Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China, and the Struggle for Western Pacific. He can be reached at @Richeydarian

Be the first to comment