BY BHARAT H DESAI & BALRAJ K SIDHU

India‘s moving the International Court of Justice to seek justice for Kulbhushan Jadhav, a former naval officer who was sentenced to death by a Pakistani military court vindicates the majesty of international law. It also vindicates the need for India to take international law more seriously across the board as an instrument of state policy.

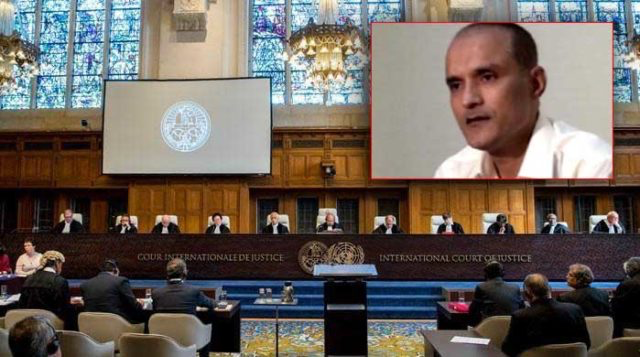

Long arm of law: Hopefully, the ICJ action in the Jadhav case will bring about sobriety in Pakistan”s behavior and it will back off from the brink.

India has made a deft move to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) seeking justice for its national, Kulbhushan Jadhav, a former naval officer, who was sentenced to death by a Pakistani military court. This is the first such action by India as it had hitherto refrained from taking any bilateral issue to international forums or judicial bodies (courts and tribunals). This action has been triggered by the consistent denial by Pakistan of “consular access”, a minimal courtesy exercised by all civilized states, to Jadhav as a national of India. India expressed determination to rescue Jadhav from the Pakistani custody as it viewed the case as stage-managed abduction, slapping of false espionage charges and secretive military trial leading to imposition of death penalty.

Notwithstanding lack of “compulsory” jurisdiction of ICJ, India sought to tap the legal remedy available under Article 36 (1) of the ICJ Statute (all matters provided for in treaties and conventions in force) and Article 1 of the Optional Protocol Concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes (1963) to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (1963). The Optional Protocol provides that “unless some other form of settlement has been agreed upon by the parties…Disputes arising out of the interpretation or application of the Convention shall lie within the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and may accordingly be brought before the Court by an application made by any party to the dispute being a Party to the present Protocol”. As of May 2016, the Protocol was ratified by 51 states and, amazingly, included both India and Pakistan!

This represents a growing trend, wherein a state party seeks to raise issue of breach of specific treaty obligation by another state. For instance, Ukraine has taken the Russian Federation to ICJ for breach of Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism and the Convention on Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination.

It is the first such resolute support provided by India to rescue a national, accused of violations of local law in another country. Due to the unusual situation prevailing in Pakistan as well as regular incidents of aiding and abatement of cross-border terror chain of pinpricks, India has been forced to bypass time tested rule of “exhaustion of local remedies” as they are in any case not available due to the current impasse.

The Indian action has been buttressed by turning down of more than 15 requests for consular action by the Pakistani authorities. In a petition filed in the registry of the ICJ in The Hague, India underscored the urgency of this situation. It referred to the provisions of Article 75 of the Rules of Court, asked the Court to indicate forthwith, and without holding any hearing, provisional measures proprio motu. As laid down by the ICJ Vienna Convention on Consular Relations case (Paraguay v. USA case; April 9, 1998), the Court could order interim measures if there is possibility of “irreparable prejudice…to rights which are the subject of dispute…”. As a corollary, in a swift move, the President Rony Abraham issued an order to Pakistan to “act in such a way so as to enable the court to enforce any decision it takes on the Indian plea.”

As a founding member of the United Nations, India has been forced to move to ICJ not for violations of sovereignty per se but breach of an international treaty obligation – the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, 1963. India has otherwise consistently denied efforts of countries like Pakistan to drag her to ICJ on the basis of the “Commonwealth Clause” in declaration under Article 36 (2) of the Statute of ICJ. Pakistan’s steadfast refusal to allow consular access to Jadhav has lent credence to Indian claim about “fixing” of Jadhav, circumstances of his alleged abduction and “sale” in early 2016 to elements in Pakistan and slapping of “espionage” case even though it was proved he was carrying an Indian passport. This, as India argued, “has prevented India from exercising its rights under the Convention and has deprived the Indian national from the protection accorded under the Convention”. The issue at stake has been the nationality of Jadhav and the prevalent right of India to provide diplomatic/consular protection to Jadhav. The case has assumed grim proportions since efforts were stonewalled by Pakistan to allow consular access to him. Demarche issued to the Pakistan High Commissioner were ignored and all pleas at the highest level fell on deaf ears. It has placed bilateral relations in serious jeopardy.

The Indian contention in the Jadhav case is rooted in Article 36 (1) of the Vienna Convention that guarantees unimpeded consular communication, access and providing of legal representation by a ‘sending state’ to its nationals who are arrested or committed to prison pending trial or detained in any other manner. Pakistan’s consistent and willful denial of India’s right to provide consular protection to Jadhav has led to the ICJ to underline sanctity of the Convention as well as efficacy of the remedy available under the Optional Protocol. Indian legal recourse is a cogent step to obtain judicial restraint of Pakistan’s aberrant conduct resulting in not only gross violation of India’s consular right but also basic human right of Jadhav under Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This provides every human being the inherent right to life.

Generally, the UN member states take matters to ICJ on issues concerning territorial integrity and sovereignty like delimitation of land and maritime borders or other violations. It is rare that states contend before ICJ issues concerning rights of a corporate entity (Interhandle case by Switzerland against USA) or individuals (Asylum case by Columbia against Peru). In 1980, the USA also had to ICJ against Iranian revolutionary guards’ seizure of the US Embassy in Tehran. In the famous LaGrand case (1999), the ICJ upheld German contention that the USA violated the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations by not advising its national Karl and Walter LaGrand on their right to consular access that prevented Germany from obtaining effective trial counsel for them. In spite of repeated German assertions Karl La Grand was executed in the state of Arizona on February 24, 1999. The ICJ did grant urgent provisional measures and stayed the execution of Walter LaGrand that was slated for March 3, 1999.

India had no choice amidst the groundswell of domestic public opinion as well as to counter Pakistan’s compulsive “irritation” campaign to ward off international isolation. The decisions given by the ICJ are binding on the parties to the dispute. There are glaring cases of defiance in the past by countries such as USA (Nicaragua case) and Iran (Hostages case). Still Pakistan can defy ICJ only at its own peril and at the cost of irreversibly damaging India-Pakistan relations. In this grim scenario, Indian recourse to this international law remedy has brought about a glimmer of hope. It provides a robust message that it will work wonders if India takes this vital instrument more seriously in internal governance structure as well as in the conduct of external affairs and, in turn, for maintenance of international peace and security.

(Bharat H Desai is Chairman of Centre for International Legal Studies, JNU. Balraj K Sidhu is faculty member of RGSOIPL, Indian Institute of Technology-Kharagpur)